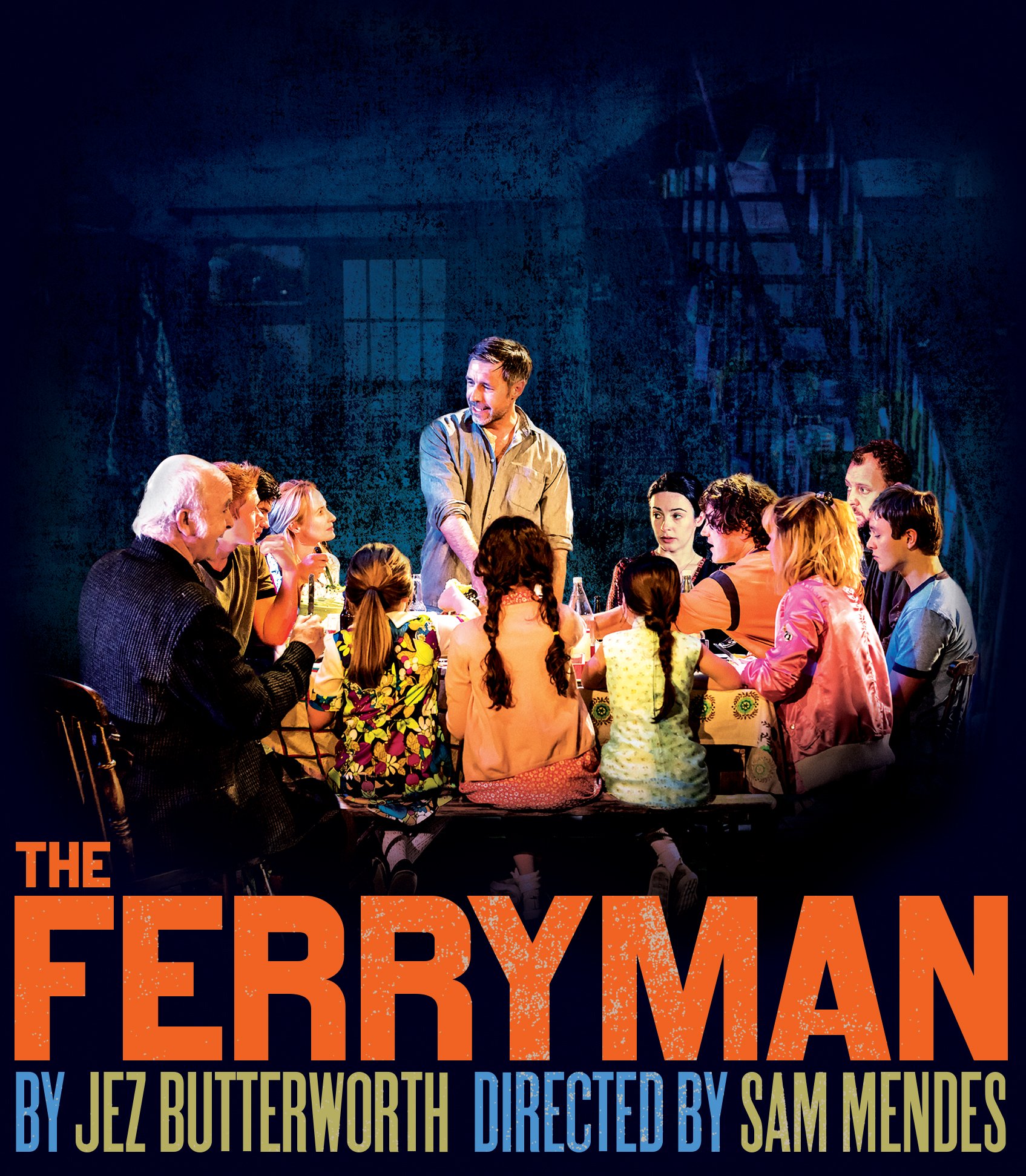

09 Oct TIO NYC: “The Ferryman”- Visually Stunning, Utterly Shattering, Overall Superb

A ferryman demanding payment is a direct reference to the Greek ferryman of the dead. Charon was known to demand an obolus (coin) to ferry dead souls across the River Styx. Those who did not pay were doomed to remain as ghosts on the plane of the mare.

The restless dead are everywhere in Jez Butterworth’s “The Ferryman” – and very soon, more will join their phantom legions. The soul-shattering dramedy which curses (even the kiddos) and cries, is profane and superb and not to be missed.

The soulful wailing and keening of the banshees, those “women of the fairy mound” who herald the death of a family member tell us The Reaper has joined the Carney family at their farmhouse table too, planning to reap way more than the annual yield from the harvest everyone is gathered to collect from their modest 50 acres.

So does Aunt Pat, Ferryman’s Cassandra.

Comparisons to “August: Osage County” abound. But the play by Tracy Letts is simply a very smart, often funny drama about a wildly dysfunctional family.

In contrast, “The Ferryman” is about today.

It is about hate and how we reap what we sow.

Carpe diem.

Northern Ireland, Rural Derry, 1981, nighttime. The local ringleader of the Irish Republican Army gun-toting comrades ambushes a priest and tells him that the body of one Seamus Carney has been recovered. It is said the man had spent a full 10 years as a restless dead preserved in a bog. The IRA heavy, Muldoon, orders the priest to tell the Carney family not to utter a word about what happened.

Or else – and then Muldoon has one of his heavies flash a photo of the priest’s sister, his only living relative.

Morning at the home of the Carney family.

Quinn and Caitlin Carney enjoy the peaceful dawn of a new day. Quinn, a handsome, sturdy farmer – and former IRA assassin – is prepping for the celebration of the harvest, a joyful day, a day of togetherness and bounty.

Quinn teases Caitlin, asking if she only had one car with her to save four people in mortal peril, who would she save? Would it be The Beatles, The Stones, or Led Zeppelin? “Led Zeppelin.” He implores, until she relents, agreeing to combine the lot and take Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, and any one of The Beatles with her — also Keith Richards, but only if he takes a bath.

Cue the (momentary) laughter in the room.

However, the pastoral is interrupted by one of Quinn’s brood, little Honor, who reminds her da’ that it’s time for breakfast. Light comes into the room; the entire family is fast awakened, among them: Uncle Pat, who quotes Virgil for one; bitter Aunt Pat, who is obsessed with her dead IRA brother and the cause; mystical Aunt Maggie Far Away, who tells tales of the frightening fairies – when she speaks at all; Quinn’s seven children; the sickly Mary who suffers from a never-ending virus (of the heart?); and a gentle-giant English simpleton of a farmhand who has been living with the Carneys since he was a lost boy.

Caitlin exits the scene. She is not Quinn’s wife as it turns out, Mary is, but for the past decade, she has been pining under Quinn’s roof with her teenage son Oishin, waiting for news of her husband.

Or at least waiting…

We soon will find out the fate of the Carney clan is plagued by far more than Quinn’s and Caitlin’s doomed longing for each other – or even Seamus’ disappearance.

“The Ferryman” is a three-and-a-half-hour meditation on the fickleness of ideals and dark side of obsessions that explores war, politics, poverty, social tension, justice, hidden desires – and vanishing.

In fact, the inspiration for the deeply moving story came from the disappearance of a man named Eugene Simons, the uncle of Butterworth’s wife, Laura Donnelly, who played Caitlin during the first run.

Simons was a former IRA activist who disappeared in 1981, only to show up dead in 1984. Eventually his name was added to the list of the “Disappeared,” people believed to have been abducted, murdered and secretly buried during the Troubles of the early 1980s.

By unearthing that deeply personal tragedy, the writer succeeds in creating “The Ferryman,” which is lovingly, perfectly directed and choreographed by Sam Mendes and beautifully acted by, well, everyone in the large cast of more than 20, which includes a live rabbit, a live goose and a beautiful baby.

What could possibly go wrong?

Through Mendes, Butterworth’s tale of common folk of Northern Ireland, farmers like the Carneys, the old and the young, people who want nothing whatsoever to do with violence but who, like so many others, have been dealt a rotten hand, becomes a universal meme for the heritage of hate.

Here is Ben Brantley‘s review of the award-winning show for The New York Times before the production crossed the pond.

It’s a mighty full house that’s presided over by Quinn Carney, the divided Irish hero of Jez Butterworth’s “The Ferryman,” which burst open at the Royal Court Theater here on Wednesday night, where its run is already sold out. (It moves to the West End in June.) The fiercely gripping play in which Quinn, a father of seven, appears is every bit as crowded.

And I mean teeming — with characters, plot, secrets, confessions, clashes political and sexual, betrayals, murders, ballads, poems, dancing, drinking, wrestling and the wails of banshees, whose reality is not to be doubted. The terrific cast — led by Paddy Considine and directed with a racing pulse by Sam Mendes — numbers 21, and that’s not counting the baby, the rabbit and the goose. Like everything else in “The Ferryman,” those nonspeaking performers are indisputably alive.

Set in rural Northern Ireland in 1981, this latest offering from the author of “Jerusalem” also overflows with storytelling vitality, the kind that so holds the attention that three and a quarter hours seem to pass in the blink of an eye, albeit a bloodied and black one. Consider yourself well warned when a little girl, gleefully awaiting an oft-told tale by an ancient relative, chirps excitedly: “I love this one! It’s so violent!”

That scene exudes the hearthside warmth of a classic, bustling domestic comedy in which an extended family lives in contented close quarters and everybody chips in to help. Of course, in this clan, even the little ones swear like sailors on a bender.

And the yarns spun by old Aunt Maggie Far Away (Brid Brennan), who spends much of her time in a wordless trance that might be mistaken for senility, feature the dismemberment of faerie warriors and are steeped in an erotic longing for the golden lad she once loved from a distance, now long disappeared. “I swear to Christ,” she says sweetly to the little ones gathered at her feet, “I could have ridden that boy from here to Connemara.”

Like much of “The Ferryman,” Ms. Brennan’s character (right down to her name) would seem to be drawn with an exaggeration that borders on parody. But as he demonstrated in his astonishing “Jerusalem,” seen on Broadway in 2011, Mr. Butterworth specializes in making what might be too much from anybody else feel somehow exactly right.

Life as he portrays it is so expansive, only myth and melodrama can accommodate its dimensions. And under the expert guidance of Mr. Mendes, an acclaimed film director (“American Beauty,” “Skyfall”) returning to the stage with avid conviction, “The Ferryman” embraces and absorbs explosive contradictions of story and sensibility.

The play begins with a stark, sinister scene that scarcely prepares us for the richness of what follows. We’re on a grimy back street of Derry, where Father Horrigan (Gerard Horan), a country priest, has been dragged for a meeting with the notorious Mr. Muldoon (Stuart Graham), a lean man of elegant menace.

It seems the bound corpse of one of Horrigan’s parishioners, missing for a decade, has been found in a bog, and Muldoon wants the good father to carry the news to the dead man’s brother. That’s Quinn, whom we meet at home in the next scene, dancing wildly in the wee hours to the Rolling Stones with a woman we assume is his wife or a lover.

She’s not. Caitlin Carney (Laura Donnelly) is Quinn’s sister-in-law and the wife of the dead man. Don’t trust your first assumptions as you watch this play; don’t entirely discount them either.

Quinn’s household includes his bedridden wife, Mary (Genevieve O’Reilly); a married aunt and uncle, both called Pat (Dearbhla Malloy and Des McAleer); Caitlin’s teenage son, Oslin (Rob Malone); and a slow-witted handyman, Tom Kettle (John Hodgkinson), who was taken in as a child after being abandoned by his parents, who were (and this is crucial) British.

It is harvest day. There’s to be toiling in the fields and the kitchen, and drinking and feasting after. It would all be perfectly jolly, except for our niggling awareness of the shadows cast, by that opening scene with Mr. Malloy and by news of the fatal hunger strikes of Irish Republican Army prisoners in the Maze prison. That darkness thrums like a bass line.

“The Ferryman,” as you may have inferred, is Mr. Butterworth’s contribution to the literature of the conflict known as the Troubles, and on one level, it recalls Sean O’Casey’s epochal dramas of civil war from the 1920s. But Mr. Butterworth is digging beyond the tensions of political factionalism to uncover more atavistic impulses.

Like “Jerusalem,” which probed the British yearning for a lost mythic grandeur, “The Ferryman” portrays a people in thrall to millenniums of history, in ways they’re not always aware of. On the one hand, there’s the embittered Aunt Pat, who as a girl witnessed the death of her brother during the Easter Rebellion and can’t stop talking about it; on the other, there’s the fey Aunt Maggie, with her gossamer-spun stories of elfin wars and lost loves.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.