03 Oct TIO NYC: What Not to Miss, Fine Art – So Far…

Picasso famously said “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.”

Paul Klee had no such problem: when he grew up, the iconic artist managed to hold on to a child-like vision and yet, and still, be profound, proving that “youth has no age.” (Picasso again.)

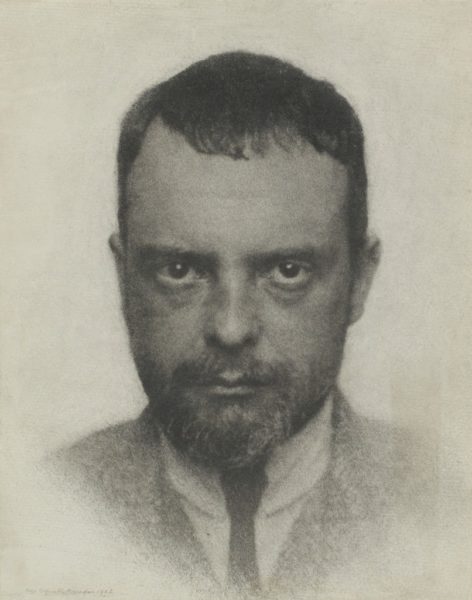

Hugo Erfurth

Portrait of Paul Klee, 1922

“Paul Klee: L’ironie à l’oeuvre” at Centre Pompidou, Paris.

The Dadaists saw in Klee a man who had plumbed the depths of the unconscious and the power of the act of creation itself.

His doodles inspired the “automatism” of the Surrealists.

Klee famously said “The line likes to go for a walk.” On one of those hikes, the line wound up on Miro’s doorstep.

In his last years, Klee’s dark and brooding signs of “Secret Letters,” 1937, hit one contemporary artist square in his gut. Imagine Klee’s thick, dark lines yawning and stretching to all corners of the canvas and voilá, Jackson Pollack.

In the end, Klee’s DNA informed modernism like few other major artists have.

From “Humor and Fantasy.”

MUST SEE: An installation of works from The Berggruen Klee Collection—the largest collection of works by Paul Klee in the United States—is on view at The Met Breuer through December 31, 2016.

“Humor and Fantasy—The Berggruen Paul Klee Collection” features 70 works from the family’s collection, which spans the artist’s entire career, from his student days in Bern in the 1890s to his death in 1940 at the age of 60.

In 1984, Heinz Berggruen and his family donated 90 works by Paul Klee (1879–1940) to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. These 11 paintings, 71 watercolors, and eight black-and-white drawings constitute one of the most important gifts in the history of the Museum and established The Met as a major center for the study of the German artist.

The earliest work in the collection is a precisely penciled view of Bern, drawn in 1893 when Klee was only 13-years-old; the latest is a gouache painted in 1940. More than half of the works in the collection were executed during the painter’s most active years, 1921 through 1931, when he taught at the Bauhaus, first in Weimar and then in Dessau. Marcel Breuer, the architect of The Met Breuer, was also a faculty member and one of Klee’s colleagues at the Bauhaus.

Promise, this show will be a revelation, even to Klee fans and followers. It was to us. The full force of the man’s abundant charm, wit, hypertrophic fantasy never diminishes, even towards the end when Klee was suffering from a rare and terrible disease of the tissue that ultimately ended his life.

Like Picasso, another creative titan and game-changer, Klee’s virtuosity as an artist, his extreme fecundity, has never been and never will be in question: his images beget other images. Like horny beasties in Petri dishes, they just keep on keeping on….

résentation du Miracle, 1916

“Paul Klee: L’ironie à l’oeuvre” at Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Want more?

Here’s a wonderful article from artsy.net about the master.

Paul Klee (1879-1940) has been called many things: a father of abstract art, a Bauhaus master, the progenitor of Surrealism, and—by many an art historian and fan (members of his cult following affectionately refer to each other as “Klee-mates”)—a very hard man to pin down. Indeed, the Swiss-German artist’s paintings are tied to numerous groundbreaking 20th-century movements, from German Expressionism to Dada. But Klee’s body of work isn’t easily bucketed into a single category, thanks in large part to the system of throbbing forms, mystical hieroglyphs, and otherworldly creatures that he developed to populate his compositions.

These symbols marked some of the first efforts in the 20th century to embed spiritual content and the subconscious into abstract art. In turn, they inspired both Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, whose influential practitioners, from Joan Miró and Salvador Dali to Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, cited Klee as a lodestar. This spring, Klee’s enigmatic but influential work is celebrated at Paris’s Centre Pompidou in “L’ironie à l’oeuvre” (“Irony at work”). What follows is an exploration of the many influences and aftershocks of the artist’s strange and singular work.

Why does his work matter?…

Another MUST: Juan Genovés at the Marlborough, through October 8. The man is one of Spain’s best-known contemporary artists, recognized for work rooted in Social Realism and Pop with a distinctly critical voice that advocated for political change during the Franco regime in Spain.

Working with acrylic paint in an astounding, obsessive impasto style to create a distinct cinematic quality, Genovés’ art repeatedly addresses two subjects: the “individual” and the “multitude.”

Many of his works explore the concept of a crowd in which groups of people are pulled toward a force they cannot control. Genoves’ works depict bird’s-eye views of empty landscapes devoid of buildings, roads, trees, or contextual clues, creating a sense of anxiety and dislocation. The motivation for the groups’ activities? Not clear. The viewer is asked to draw his own conclusions.

NICE TO SEE:

Charlotte Brontë (1816 – 1855) at The Morgan. Little waist. We are talking 18 1/2 inches small. Big voice: “Jane Eyre” was published in 1847. And through her timeless, brave, rebellious character she herself declared: “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will.” Show traces her creative path from untethered teen to reluctant governess to masterful novelist through manuscripts, letters, rare books, artifacts and drawings, including an iconic portrait from London’s National Portrait Gallery. (Through January 2, 2017.)

Hans Memling, (1440 – 1494) also at The Morgan. Memling towered over the Northern Renaissance. Two panels from his Trptych of Jan Crabbe are on display. That and a number of independent portraits reveal the artist’s uncanny ability to capture not just a likeness, but the heart and soul of his sitters. And by humanizing his subjects, the artist humanizes himself. (Through January 8, 2017.)

Portrait of a Man with a Pink.

Carmen Herrera (1915 – ) at the Whitney. The iconic art critic Clement Greenberg would have loved her – if he knew of her. And he might have, but chose to immortalize Frank Stella and other Color Field, art-for-art’s-sake types, from the fraternity, which excluded the Cuban minimalist for years and years – though Herrera was doing Stella at the same time Stella explored art as a thing unto itself, not referring to anything else.

“Lines of Sight” is the first museum exhibition of this groundbreaking artist in New York City in nearly two decades. Focusing on the years 1948 to 1978, the period during which Herrera developed her signature style, the show features more than 50 works, including paintings, three-dimensional works, and works on paper. It begins with the formative period following World War II, when Herrera lived in Paris and experimented with different modes of abstraction before establishing the visual language that she would explore with great nuance for the succeeding five decades.

The work is handsome, architectural, muscular, minimal.

Bianco-Verde, Herrara

Also Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney Collection (through February 12, 2017), includes work by Andy Warhol, Alice Neel, Berkeley Kendricks, Edward Hopper, Jasper Johns and Georgia O’Keefe.

And while trolling Chelsea, check out the Alfred Leslie (born, 1927) show at the Bruce Silverstein Gallery. “The Toast Is Burning” (through November 12) features new work by the artist, plus a selection of large-scale portraits from the 1960s.

Despite his exposure to abstract paintings and films, by the mid-1960s, Leslie had shifted his focus to realism that led him to becoming a brand name in American painting. The switch allowed the artist to be true to his tropism towards the narrative and the acceptance of artifice as a fact of life to be embraced, not avoided.That led to the realization of what is undeniably a quirky, confrontational style of human portraiture.

Reno

And the new work reveals that Leslie continues to be a pioneer. Pixel Scores are digitally painted portraits of characters from literature, ranging from Benito Pérez Galdós’ 1887 novel “Fortunata and Jacinta,” to Jennifer Egan’s “A Visit from The Goon Squad,” 2010, and Rachel Kushner’s “The Flamethrowers,” 2013—comprising a larger series entitled “50 Characters in Search of a Reader.”

In his recent interview with Phong Bui of the Brooklyn Rail, Leslie stated:

“There’s a straight line from my post abstract paintings to the Pixel Scores…The Pixel Scores are not better because I do it this way—they’re just different in that it’s my way. We all work to put together the discontinuities of the things that we see all the time…I like to think of everything as automatic artifice, from images greatly disproportionate in scale to kitschy images of marshmallow clouds and whatnot, it’s all intermingled in these Pixel Scores. It’s all complete artifice, bound together—I hope—by first-class formal attributes.”

More as we continue trolling the art scene….

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.