31 Dec TIO NYC: HANGING WITH WASSILY, HENRI AND GEORGE

On a two-day whirlwind trip to the Big Apple, we hung with a group of artists who lived at the same time and were similar in the fact they marched to their own drum. Or drums. Since their chosen paths were very different. One was part of a tribe of recalcitrants and rebels. The other two operated as lone wolves, but attracted adoring fans and imitators.

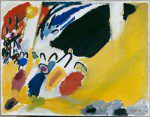

Wassily Kandinsky was to modern (read abstract) art what Edison was to the light bulb: arguably he invented it. But unlike Edison, Kandinsky was not alone.

Kandinsky’s pioneering treatise, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art ,” is to abstract art what the Bible is to Christians and the Koran is to Muslims. In its hallowed pages, the artist-prophet lays out his belief that art should aspire to be spiritual in nature. It should be an expression of an “internal need” meant to convey messages from the soul. In so doing, artists inhabit the tip of an upward-moving pyramid, penetrating and proceeding into the future. What was odd or inconceivable yesterday is commonplace today; what is avant garde today (and understood only by the few) is common knowledge tomorrow.

But if line and color could elevate, surely harmony and rhythm in music could do the same. Or movement in dance. And those ribbons of dreams we call film need not be linked to linear narratives. Just what was the relationship among the arts?

Kandinsky was known to hear tones and chords as he painted and theorized that yellow was the color of middle C. He was reputed to have created his first abstract composition after attending a concert of the music by composer Arnold Schoenberg.

As WWI raged, the art world with all of its appendages came under attack too. The result of that assault was one of the most exciting, radical, innovative periods in the history of all the arts, one that proved early on that it really does take a village. In inventing abstraction, Kandinsky was joined by a fraternity of other painters, plus sculptors, composers, poets, photographers, filmmakers and choreographers, mostly Europeans and Russians, hellbent on liberating their disparate mediums from time-honored links to easily recognizable forms.

Their work is on display now in the Museum of Modern Art’s sweeping survey of the volatile scene, “Inventing Abstraction, 1910- 1925.”

For an edifying review of the show, follow this link.

“Inventing Abstraction” runs through April 15, 2013.

From MOMA, we braved the crowds in town for the holidays – kids in tow egads – to visit several shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, including “In Search of True Painting,” featuring the work Henri Matisse.

Like Kandinsky & Co., Matisse achieved great acclaim during the first half of the 20th century. And like Kandinsky, he was a master colorist – though likely more about color for color’s sake than spiritual transcendence. And Matisse appeared not to be attracted to “isms” of any stripe. Unlike his arch rival Picasso and the other aforementioned abstract artists, he was not involved with parsing the old for the sake of a building a whole new language of painting. Instead, Matisse wrote his own script, which was all about pushing, as he put it, “further and deeper into true painting.”

Writing in The Nation in 1949, critic Clement Greenberg described the artist as a “self-assured master who can no more help painting well than breathing,” a quote that suggests an effortless labor of love by a facile genius. The truth is otherwise: unbeknownst to many, painting did not come easily to Matisse. The old rule, “two percent inspiration; 98 percent perspiration” applies here.

“Throughout his career, Matisse questioned, repainted, and reevaluated his work,” explained Rebecca Rabinow, curator. “He used his completed canvases as tools, repeating compositions in order to compare effects, gauge his progress, and, as he put it, ‘push further and deeper into true painting.'”

Though working with pairs, trios, and series is certainly not unique to Matisse – think Monet’s haystacks and Notre Dame – his need to progress methodically from one painting to the next is striking. (A great example in the show may be the exhaustive process, recorded for posterity by a photographer friend, in the creation of “The Dream,” which the artist created over the course of one year.)

Through 49 lushly colored canvases, “Matisse: In Search of True Painting” showcases Matisse’s idiosyncratic process, clearly not a means to an end, but an end unto itself that appears to be as important as the dazzling finished product.

For an in-depth review of the show, go here.

“Matisse: In Search of True Painting” runs through March 17.

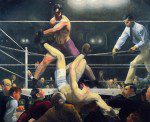

Say the name “George Bellows” and one stand-out painting comes to mind. And it’s quite literally a knock-out.

His “Dempsey and Firpo” immortalized the famous four-minute championship fight, which opens with Firpo knocking Dempsey out of the ring into the press pit. In response, the media gave the favorite a leg up. Back into the ring, in the second round, Dempsey knocked out Firpo for the win. Bellows, on assignment covering the event, produced this signature image just six months before his premature death at age 42, his career still a work in progress. Acknowledging his important role in American art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art immediately organized the artist’s first museum retrospective in 1925 as a memorial exhibition.

As a member of the Ashcan school, which was known for chronicling daily life, Bellows’s claim to fame did indeed rest on his in-your-face depictions of boxing matches, also gritty scenes of New York City’s tenement life. But there was more, much more, and therein lies the strength of the retrospective exhibition.

Bellows also painted dynamic cityscapes, majestic seascapes, sobering war scenes, and insightful portraits. He made illustrations and lithographs that addressed many of the social, political, and cultural issues of the day.

Featuring about 100 works from Bellows’s extensive oeuvre, the landmark loan exhibition is the first comprehensive survey of the artist’s career in nearly half a century. The show invites the viewer to experience the dynamic and challenging decades of the early 20th century through the eyes of a brilliant observer, who was less of an iconoclast and joiner, more of a rugged individualist with talent to burn.

For an interesting review of the show, one that disagrees with my assessment of Bellows worth as an artist, go here.

“George Bellows” continues through Feb. 18.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.