28 Nov TIO NYC: More (Very) Fine Art!

“Monet in Venice” is a must, an eye-dazzler of a show and a major coup for the Brooklyn Art Museum; Gabriele Münter is at the Guggenheim; Wilfredo Lam is at the Museum of Modern Art.

Monet in Venice, Brooklyn Art Museum, up through February 1.2026

Over the summer of 1921 Picasso rented a villa – essentially a garage/studio – in Fontainebleau and worked intensively there over a short span of time. While there, the legendary artist created major works including two monumental canvases: two versions of “Three Women at the Spring” and two of “Three Musicians.”

The stay reflects a moment when Picasso was deeply engaged in exploring new forms and scales outside the daily bustle of Paris, which allowed a kind of concentrated focus.

Same holds true for the other art world giant whose name is often allied with Picasso in the context of “The Last Impressionist” vs.”The First Modernist.”

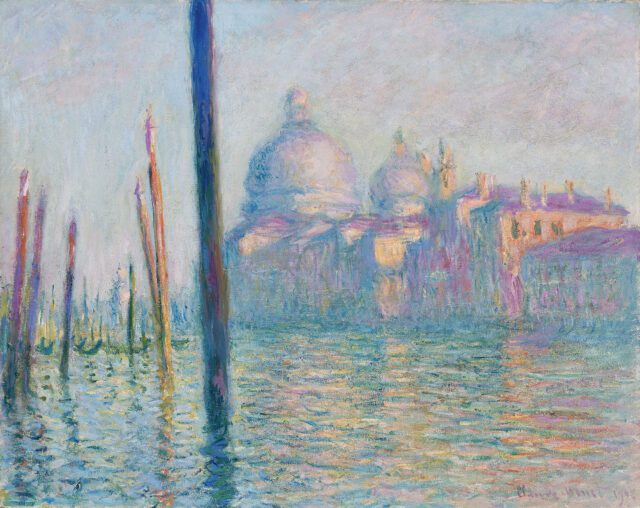

In 1908 and despite huge reservations because he deemed the city “too beautiful, too often painted by others,” Claude Monet headed to Venice for six very productive weeks.

Claude Monet, Grand Canal, Venice, courtesy Brooklyn Art Museum.

Claude Monet, Saint George, courtesy Brooklyn Museum.

The Doge’s Palace seen fromSan Giorgio Maggiore, courtesy Brooklyn Museum.

Once there, Monet became enthralled with the way the city’s architecture shimmered on water and the pink-gold Venetian light. (Little known fact- it was, sad to say, sulpher dioxide that contributed to the city’s luminosity.)

The 37 paintings he produced while there focused on the Grand Canal, the Doge’s Palace, Santa Maria della Salute, and the Palazzo Daria. All are among the loveliest works of the artist’s late career, balancing structure and atmosphere agilely, beautifully – as evidenced in the show titled “Monet in Venice,” now up at the Brooklyn Art Museum.

The exhibition, which also includes the work of other well known artists – Sargent, Whistler, Moran and Canaletto among them – besides being dazzling and revelatory was proof positive Monet’s work anticipated abstraction and prefigured the output of mid-20th century greats such as Rothko, Pollock, and Morris Louis.

Therefore, in effect, Monet’s Venice paintings felt as radical as anything in modern art. The painter seems to have invented abstraction through the simple act of perceiving. His magic trick? Dissolving form into light, effectively painting air. (Picasso, on the other hand, invented modernism through structure, shattering form into new geometric planes.)

In all, “Monet in Venice” is a tranquil, beautifully curated and arranged meditation on an aging genius who lived to paint air, light and color. It offers a rare chance to see lots of Venetian works together and positions Monet not simply as the great Impressionist of gardens and haystacks and churches, but also as a traveler briefly, but intensely captivated by the gorgeous city of reflections.

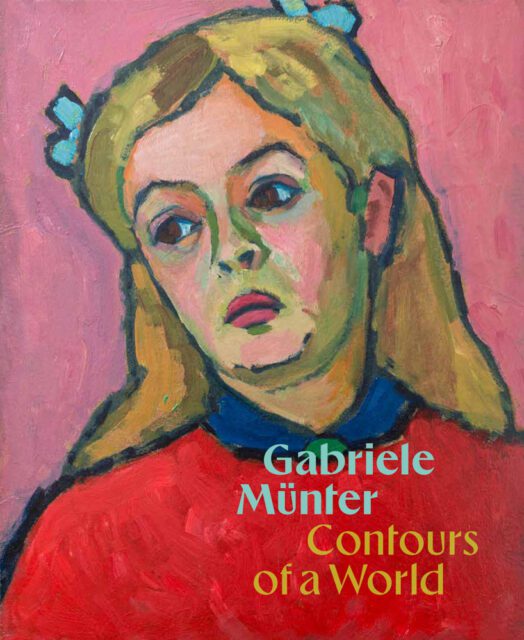

Gabriele Münter at the Guggenheim, up through April 2026

Gabriele Mûnter was a pioneer of German Expression, characterized by an emphasis on artists’ inner feelings over external reality. The movement realized that impulse through distorted perspectives, simplified, often distorted shapes, and intense, non-naturalistic colors.

Mûnter was also founding member of the Munich-based artist group Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”) along with Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc and other greats.

Like many women artists, Münter’s work was, for a long time, overshadowed by her relationship with Kandinsky. But today museums are recalibrating and her work is being shown in major retrospectives, repositioned as central—not peripheral—to modernism.

One of those jewel boxes of a show is now up at the Guggenheim Museum.

“Gabriele Münter: Contours of a World” brings together paintings and photographs of the artist. The long overdue tribute offers a bird’s eye view of her “experimental practice” (per the Guggenheim) and emphasizes her role in shaping modern art in Europe.

This reassessment brings together some 60 paintings, including vivid landscapes and portraits, as well as 19 early photographs:

“When I begin to paint … it’s like leaping suddenly into deep waters…, ” paraphrasing a quote from the artist.

Generally she could and did.

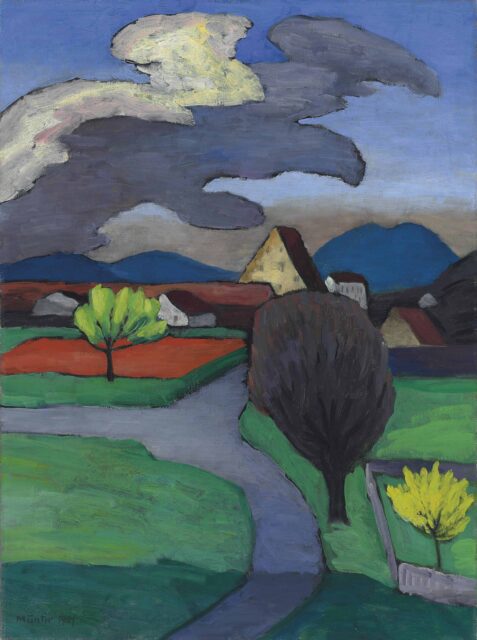

Clouds, courtesy Guggenheim.

Gabriele Autorretrato, by Munter, courtesy Guggenheim.

Münter is now rightfully and universally praised for her bold use of color, clear contours, and working across genres, namely landscape, interior, still life, portraiture, in ways that combine formal innovation with everyday subject matter. Her ability to translate what many would deem “domestic” or “local” subject matter like interiors and village landscapes into modernist terms of form and color.

A a result of the Guggenheim show (and others) , Gabriele Münter is no longer just a footnote in art history, no longer just a superstar’s (Kandinsky) companion,

Bottom line: “Contours of a World” functions both as a deep dive into Münter’s work, as well as a kind of institutional re-positioning. Critics are embracing the show for its clarity, ambition and timely corrective nature.

We second those emotions.

Wilfredo Lam at MoMA, up through April 2026

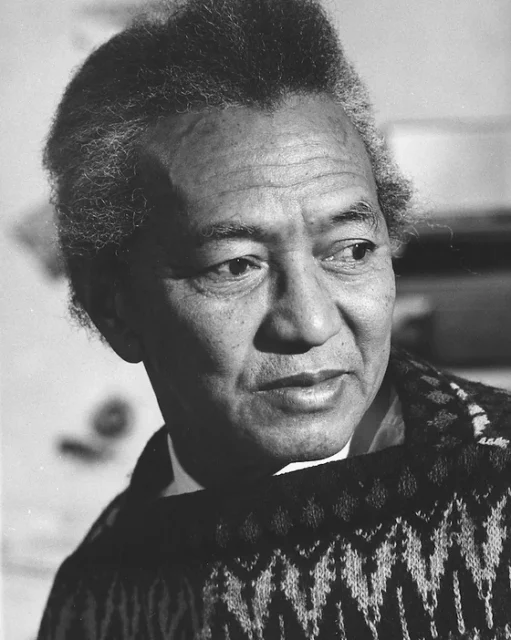

Wilfredo Lam, courtesy MoMA.

The retrospective titled “Wilfredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream,” is the first in the United States devoted to the Afro-Cuban artist. It spans six decades of the artist’s career and features more than 130 works: paintings, large-scale works on paper, prints, ceramics, collaborative drawings, archival material,

Lam was born in Cuba to a Chinese immigrant father and a mother of African and Spanish descent. His art reflects a blending of cultural ancestry, but Lam did not simply adopt Euro-modernist styles, he fused them with Afro-Caribbean iconography, symbolism, and spiritual sensibility to mesmerizing effect.

The work on display is largely big, bold, beautiful – and pedagogical (in a good way).

The exhibition at MoMA is the most extensive U.S. retrospective ever devoted to the artist. “When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” not only gives Lam a well-earned spot in the limelight, it also invites viewers to reconsider the contours of 20th-century art.

The Jungle, often viewed as Lam’s masterpiece, courtesy MoMA.

Lam at MoMA, courtesy MoMa.

The question the show artfully poses it this: What happens if modernism is not just a European/American story, but one in which Caribbean, Africa, diaspora, colonialism, etc. mixes it up with Cubism and Surrealism? (Lam was a friend of Picasso and a co-founder of Surrealism, Andre Breton, both of whom supported his efforts.)

Again, “When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” argues that modern art must include voices from the Afro-Caribbean diaspora and from transnational contexts. It is not just the Euro-American phenom.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.