06 Nov TIO NYC: Speaking Frank-ly!

Jealousy, personal politics, and the high price of lies and betrayal. individual and national. The socio-cultural-political themes of the powerful “People of the Book,” the most recent (and sadly recently closed) play at Frances Hill Barlow’s Urban Stages, could you have been snatched from today’s headlines. Yet the plot has at least as much in common with the ancient Greek revenge tragedy by Euripides.

“Medea” is about the legendary sorceress who helped Jason in his quest for the Golden Fleece. Later, betrayed by the man, she takes a horrible revenge. “People of the Books,” starred a contemporary Jason who returns from war to literary fame and fortune after writing an international best-seller. But his celebrity is underscored by his marriage to – well – Madeeha, the Iraqi woman he saved. Or was it the other way around?

The powerfully acted and directed “People of the Book” was the first stop on our fall 2024 cultural tour of New York City and surrounds.

Go here for more about Urban Stages.

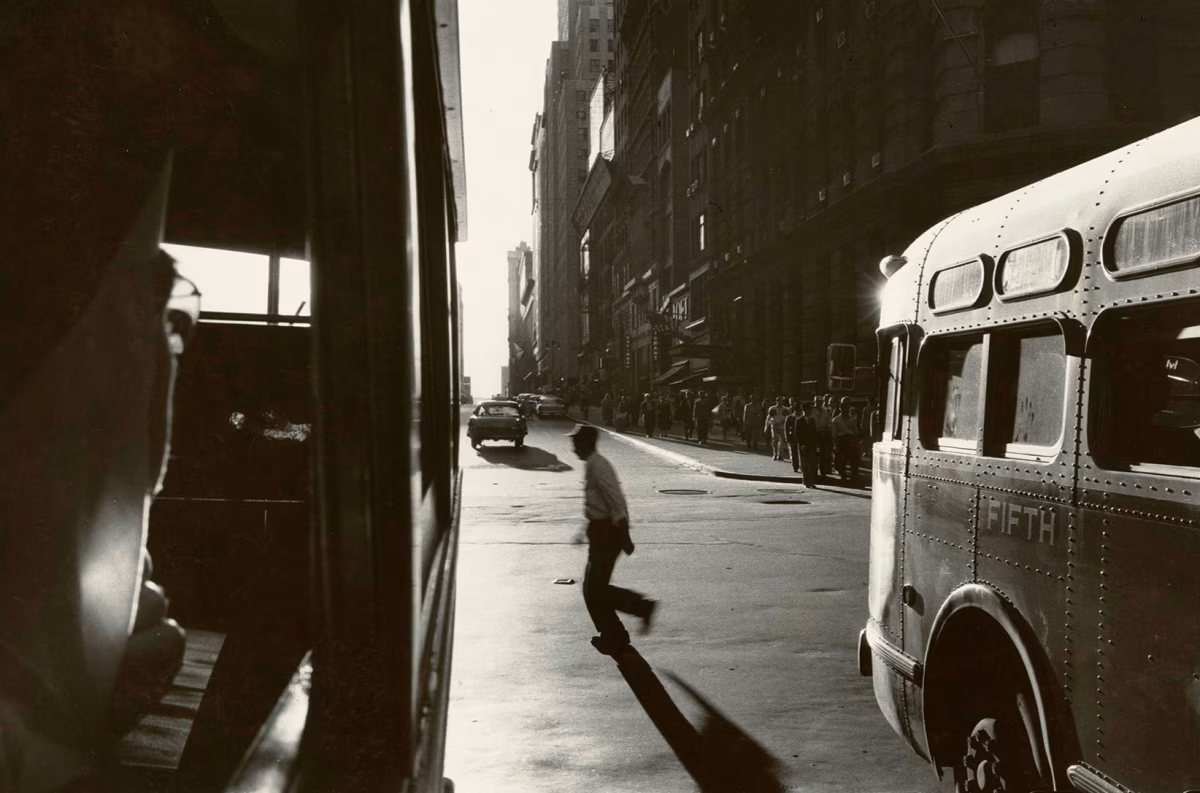

Robert Frank, “Cadillac Showroom,” c. 1955, courtesy Edwynn Hook Gallery.

“Life Dances On,” the work of Robert Frank, at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) through January 11, 2025.

“I was very free with the camera. I didn’t think of what would be the correct thing to do; I did what I felt good doing,” Robert Frank.

Next up, an afternoon at the Museum of Modern Art, which picks up on the “People of the Books'” gritty and somewhat melancholic vision with the work of easily one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. “Life Dances On.” is all about the life and work of Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank. Tying our threads together, like the “People of the Book’s author, Yussef El Guindi, Frank eschews sentimentality for the beauty in truth, rendered in his case by crooked, grainy, high-contrasts in black and white. Or Frank thumbing his nose at the medium’s bias towards prettifying.

To Frank’s way of thinking, a true artist had to be both intuitive and “somehow enraged.” In short, his goal was to use his lens to capture ways in which his environment, writ large, impacted him on a personal level. Art history says Frank succeeded where others had failed by representing not only the ordinary lives of his subjects, but also by revealing something of their souls.

His legacy:? Frank is widely considered the Father of Modern Documentary Portraiture.

According to MOMA:

“’I think of myself, standing in a world that is never standing still,’ the artist Robert Frank once wrote. ‘I’m still in there fighting, alive because I believe in what I’m trying to do now.’ ‘Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue’ — the artist’s first solo exhibition at MoMA – provides a new perspective on his expansive body of work by exploring the six vibrant decades of Frank’s career following the 1958 publication of his landmark photobook, ‘The Americans.’

“Coinciding with the centennial of Frank’s birth, the exhibition explores his restless experimentation across mediums including photography, film, and books, as well as his dialogues with other artists and his communities. It includse some 200 works made over 60 years until the artist’s death in 2019, many drawn from MoMA’s extensive collection, as well as materials that have never before been exhibited.

“The exhibition borrows its title from Frank’s poignant 1980 film, in which the artist reflects on the individuals who have shaped his outlook. Like much of his work, the film is set in New York City and Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where he and his wife, the artist June Leaf, moved in 1970. In the film, Leaf looks at the camera and asks Frank, ‘Why do you make these pictures?’ In an introduction to the film’s screening, he answered:’Because I am alive.'”

From the Bus, image, courtesy Financial Times.

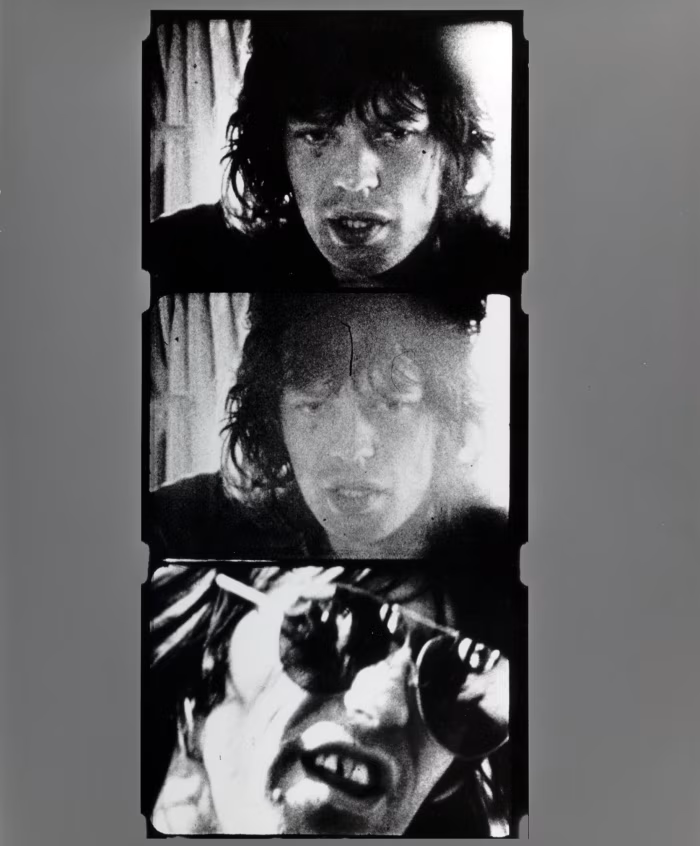

Image, Mick Jagger, courtesy Financial Times.

Go here for a full review from the New York Times.’

“Crafting Modernity: Desire in Latin America. 1940 – 1980.” Through 11/10.

According to online sources Latin America began to be considered a “seat of modernity” starting in the 1940s., a fact that can be attributed to a period of rapid industrial expansion, urbanization, and a burgeoning design movement that embraced modernist aesthetics, particularly in architecture. This movement often incorporated elements of local culture while expressing a forward-looking vision of progress and national identity.

That aesthetic surge was fueled by economic changes brought on by World War II and a shift away from reliance on European markets. The era saw the institutionalization of design as a profession, leading to new creative avenues and a reimagining of public spaces within cities across the region. Its primary laboratory and the site of some of the audacious and appealing experiments? The home.

If you can make it before the show’s imminent close, GO! We were floored – or rather chaired – and left wanting more.

A visitor looks at “Malitte Lounge Furniture” by the Chilean artist Roberto Matta at the Museum of Modern Art.Credit…Clement Pascal for The New York Times.

From MOMA:

“’There is design in everything,’” wrote Clara Porset, the innovative Cuban-Mexican designer. She believed that craft and industry could inspire each other, forging an alternative path for modern design. Not all of Porset’s colleagues agreed with her conviction. This exhibition presents these sometimes conflicting visions of modernity proposed by designers of home environments in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela between 1940 and 1980. For some, design was an evolution of local and Indigenous craft traditions, leading to an approach that combined centuries-old artisanal techniques with machine-based methods. For others, design responded to market conditions and local tastes, and was based on available technologies and industrial processes. In this exhibition, objects including furniture, appliances, posters, textiles, and ceramics, as well as a selection of photographs and paintings, will explore these tensions.

The home became a site of experimentation for modern living during a period marked by dramatic political, economic, and social changes, which had broad repercussions for Latin American visual culture. For nearly half a century, the design of the domestic environment embodied ideas of national identity, models of production, and modern ways of living. The home also offered opportunities for a dialogue between art, architecture, and design. Highlights of the exhibition include Clara Porset’s Butaque chair; Lina Bo Bardi’s Bowl chair; Antonio Bonet, Juan Kurchan, and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy’s B.K.F. Chair; and Roberto Matta’s Malitte Lounge Furniture.”

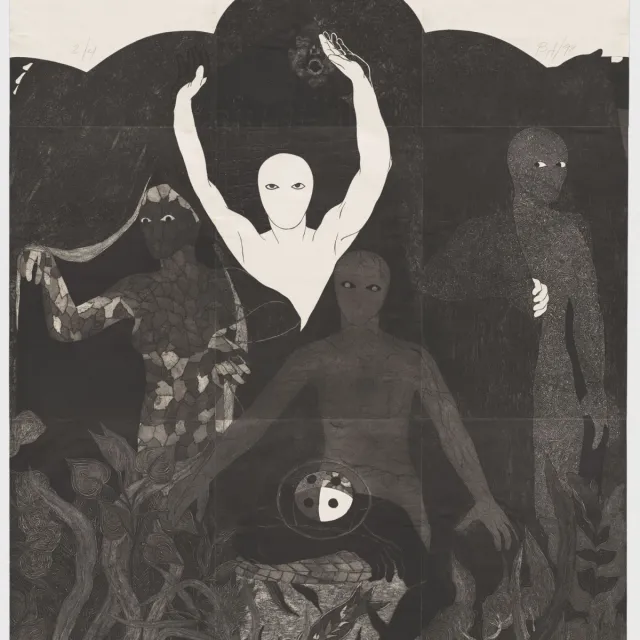

More at MOMA: “Vital Signs: Embodying Abstraction,” through 2/22/25.

This meaty exhibition offers up a fresh perspectives on celebrated works from MoMA’s collection by artists such as Frida Kahlo, Ana Mendieta, Louise Bourgeois, and Senga Nengudi, as well as works on view at the Museum for the first time. Among the new crop of artists: Belkis Ayón, Ted Joans, and Rosemary Mayer.

Some of the creatives explore the way we project, distort, and create identities through acts of play, empathy, or control. Others focus on the body’s interior – both real and imagined— or look to the world outside, forming newly imagined combinations of the human and the non-human.

Same, courtesy MOMA.

“Vital Signs” illuminates some of the ways artists reflect on abstraction in its broadest social senses, while expanding ideas around what it means to be alive and to connect with others and culture at large.

Overall, the show questions what it means to be an individual who occupies space in a larger social construct- and the reverse: how society’s precepts are reflected in individuals.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.