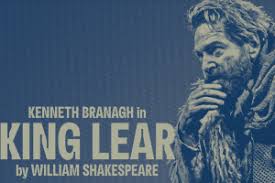

10 Nov TIO NYC: Branaugh’s “Lear,” The Unkindest Cut – But Great Abs!

Right after Election Day, an unhappy affair in our view to say the least, we saw Kenneth Branagh’s production of “King Lear,” also a less than happy affair. The show is up at Hudson Yards’ The Shed through December 15.

Let’s just say Branagh’s was the “unkindest cut of all.” Yes, that quote is from The Bard’s “Julius Caesar,” but the slight applies.

“Lear,” which generally runs about three emotionally draining hours got sliced and diced in this adaptation to a brisk two on the nose. Why the Holllywoodization of what is arguably Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy? Some critics speculate the cuts were designed to keep peeps from walking out. Others say Branagh, the lead and also the director, might have been aiming to demythologize the story, thus cutting it down to human proportions. Or was Branagh’s aim to focus on his ensemble cast and make the4 story be about a society in free fall, rather than one flawed individual crashing and burning out.

Who knows.

What we do know, however, is the result of the diet Branaugh imposed on “Lear” was an emotionally stilted effort that left us void of the kaleidoscope of emotions, many black as pitch, “King Lear”generally generates in its audience. In other words Branaugh’s production felt bleached of its hard truths.

We repeat: among the cognoscenti, uber brainy lit critics,”King Lear” is regarded as Shakespeare’s best tragedy – outranking “Hamlet.” If so, that arguably makes the tragedy the most important play by the most important playwright ever written in the English language. And why, in full plumage, does Lear’s story resonant so loudly for today’s audiences?

Could the answer have something to do with the current zeitgeist? Because the national political drama playing out in a capital near you is also a personal family drama, encapsulating two timeless, much repeated universal themes. In other words, when it’s all about politics writ large and family politics, linked and heading south, we have to pay attention: the consequences of the folly are potentially deadly. In that context, “Lear” mimics Cassandra – and today’s fetid political swamp mimics “Lear.”

“Lear” is also a play about seeing the truth – or being blind to it, literally (in the star’s sad case) and metaphorically.

The leading role of the mad king is considered the Everest of all parts for aging actors, so not surprisingly, theatrical titans such as Frank Langella, Ian McKellan, even Glenda Jackson, have assumed the royal mantle with relish, each interpreting the King’s descent into full crazy differently – as did Branagh.

Best we can say about this production is that it was a master class in acting. And oh boy, as The Guardian noted, “Branagh quite possibly the most follicularly blessed Lear since Laurence Olivier – is all Hollywood, as is the surprising third-act revelation that this Lear comes with abs.”

Yet Branaugh’s six pack is small compensation for a two-bit adaptation.

“King Lear,” a synopsis of the story (should you decide to see the production):

When the play opens, King Lear decides to abdicate and divide his kingdom among his three daughters. When the youngest (and favorite) Cordelia refuses to make a public declaration of love for her father, she is disinherited and married to the King of France without a dowry.

The Earl of Kent defends her and is banished by Lear and the two elder daughters, Goneril and Regan, inherit the kingdom.

Deceived by his bastard son Edmund, Gloucester disinherits his legitimate son, Edgar, who is forced to go into hiding to save his life.

Lear, now stripped of his power, quarrels with Goneril and Regan about the conditions of his lodging in their households. In a rage he goes out into the stormy night, accompanied by his Fool and Kent, now disguised as a servant. They encounter Edgar, disguised as the mad beggar Tom.

Gloucester goes to help Lear, but is betrayed by Edmund and captured by Regan and Cornwall who, as a punishment, put out his eyes. Lear is taken secretly to Dover, where Cordelia has landed with a French army.

The blind Gloucester meets—but doesn’t recognize—Edgar, who leads him to Dover. Lear and Cordelia are reconciled, but in the ensuing battle are captured by the sisters’ forces. Goneril and Regan are in love with Edmund, who encourages them both.

Discovering this, Goneril’s husband Albany forces Edmund to defend himself against the charge of treachery. A disguised Edgar arrives to challenge Edmund and, after fatally wounding him, reveals himself.

News comes that Goneril has poisoned Regan and then committed suicide. Before dying, Edmund reveals that he has ordered the deaths of Lear and Cordelia. He attempts to reprieve the order – but too late.

Go here for a full review in The New York Times – with which we totally agree.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.