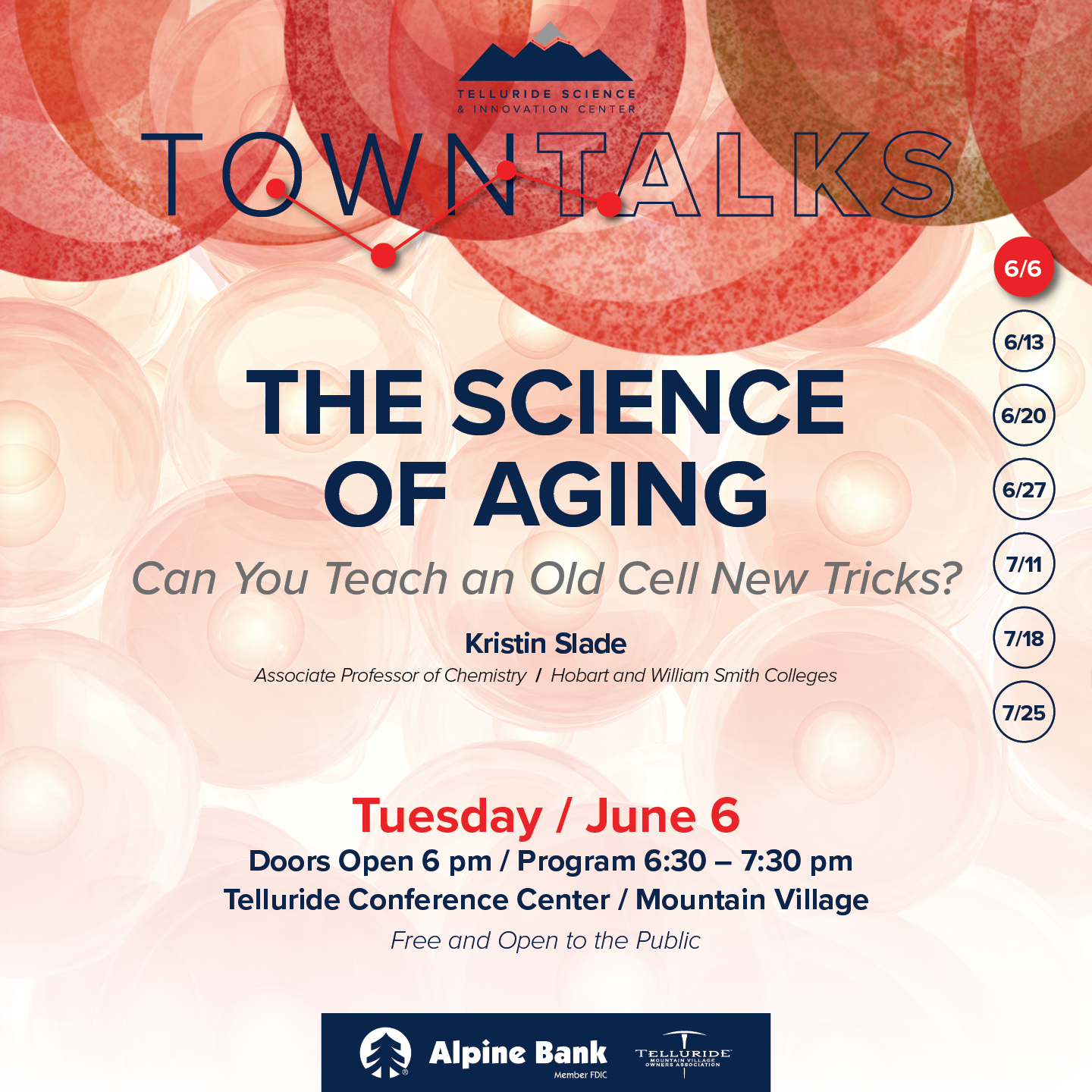

01 Jun Telluride Science: Upcoming Town Talk, “Can You Teach an Old Cell New Tricks? The Science of Aging, 6/6!

Dr. Kristin Slade opens the 2023 Telluride Science Town Talks series with a presentation titled “Can You Teach an Old Cell New Tricks? The Science of Aging.” The event takes place June 6th, 6:30 pm at the Telluride Conference Center in Mountain Village. Town Talks are free and open to the public.

Visit telluridescience.org to learn more about Telluride Science and the capital campaign to transform the historic Telluride Depot into the Telluride Science & Innovation Center, a permanent home for Telluride Science and a global hub of inspired knowledge exchange and development where great minds solve great challenges.

The 2023 Telluride Science Town Talks series is being presented by Alpine Bank with additional support from the Telluride Mountain Village Owner’s Association.

Go here for more on Telluride Science.

The dictionary defines aging as “the process of growing old.” However, Harvard Medical School professor Dr. David Sinclair disagrees. He defines aging as a disease, a perspective that suggests what we have long considered inevitable can actually be cured.

Sinclair is joined in his belief by high profile names like Peter Thiel, founder of PayPal; Larry Ellison, chairman of software company Oracle; and Larry Page of Google’s Calico, a company entirely devoted to studying aging and developing interventions.

The dollars spent today in this sector are jaw-dropping: according to online sources, over $60 billion to date on anti-aging initiatives. That number is projected to top $120 billion over the next 10 years.

At Telluride Science’s first Town Talk of the summer season, Dr. Kristin Slade of Hobart and William Smith Colleges will address the subject of “solving” aging. She will offer insight into where we are right now and what is bubbling up on the horizon.

Dr. Kristin Slade, image courtesy Telluride Science.

Slade was a curious kid:

“My parents have stories about me following them around the house as soon as I could talk, asking them a million questions about everything around us.”

Early on, Slade was passionate about math and problem-solving. She felt “science classes in K-12, similar to other subjects like history, were taught as a list of finalized facts that students were forced to memorize and spit back on an exam.” And therefore, not all that interesting. When Slade entered the University of Richmond, she believed she was destined to be a mathematician.

Once she arrived on campus, however, Slade found that chemistry was her true calling, better satiating her bottomless curiosity. One vivid memory from her undergraduate days triggered a deeper concentration in analytical chemistry. Slade pursued her PhD in the subject at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill:

“We were each given an unknown compound (in my case, it was a generic white pill) and for our final project, we could use any instrument in the department to figure out the ID of that compound. After I had turned in my lab report and was about to drive home for the end of the semester, I took a generic ‘motion-sickness’ pill for the drive home and lo and behold, the pill I bought was the same one that I had identified in the school project, verifying that I had correctly identified the active ingredient!! How cool!”

Slade defines the main role of analytical chemists as troubleshooting:

“We have other people come to us with scientific questions and we figure out how to actually use the right instrumentation or design the right experiment.”

As she advanced in her “troubleshooting” career, Slade became increasingly interested in biological problems too. In graduate school, a biology focused research lab inspired Slade to dig deeper, specifically into molecular biology. She took a postdoc in the subject at Claremont Colleges.

It was at Claremont that Slade first encountered scientific questions related to aging. In her current position at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Slade continues to pursue the biochemistry of aging.

Today, Slade studies how the amount of material inside a cell affects the activity of enzymes within that cell. In science speak, that work is all about macromolecular crowding and enzyme kinetics. Slade is “especially interested in the family of enzymes known as dehydrogenases, which play a crucial role in cell metabolism.” That research should generate more awareness on the origins of aging and disease.

“We already know what is going on with aging at the people level, but I was determined to get inside the cell and discover what was going on at the molecular level around aging.”

One answer lies in a better understanding of the epigenome.

As organisms, we have a phenome which gives us our external physical traits; a genome which makes up all of our genetic material; and an epigenome which consists of all of the chemicals and proteins that direct the expression of our genes. The sole function of the latter is to turn our genes on and off thereby regulating what function is performed, where it is done, and when it happens.

In the past, it was thought that aging was due to genetics and genetics alone. Recent research, however, demonstrates the large role the epigenome plays in this process. Slade emphasizes that “we are learning [the epigenome] is as important, if not more important, than the genes themselves.”

The epigenome “can change throughout our lifetime and is influenced by our environment, exercise, and nutrition…we are learning that plays a major role in the aging process.”

Slade emphasizes the importance of changing the mindset around aging as a natural process that cannot be cured:

“Why do we just throw our hands up and say aging is just something that happens and you know we just have to deal with it? Wouldn’t it be more powerful to throw research dollars at aging as a disease?”

Thiel, Ellison, and Page agree.

However, despite the billions of dollars and years of research dedicated to the phenomenon, Slade stresses we are still years away from being able to “cure” aging:

“As scientists we are always trained to interpret the data and only go as far as the data says and no further. So curing aging is still in the relatively early stages of research.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.