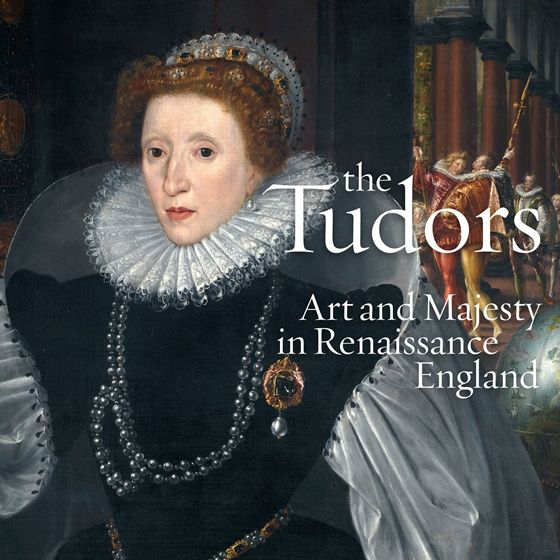

26 Oct TIO NYC: Two Shows at The Met!

“The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 8, 2023. The show begs the question: Who needs social media to be an influencer when you have – Hans Holbein? A second powerful show features the unsung slave artists of Old Edgefield in South Carolina.

Henry VIII, by Hans Holbein, one of many portraits that set the standard for royal portraiture in 16th-century England.

Holbein was one of the greatest portraitists of the 16th century, his likenesses renowned for their detail and precision. Holbein’s images of the English elite came to define their public personas in their own time – and in the centuries to come. He was Top Dog among the artists in Henry VIII’s court, establishing his brand copied (cause they had little choice if they wanted commissions) by other artists around the palaces.

Though linked to the Northern Renaissance, Holbein incorporated elements and ideas from the Italian Renaissance into his work, creating lavish and detailed images of penetrating light and deep texture. The artist’s exquisite renderings of fabric, fur, and glass speak volumes about Holbein’s extraordinary gifts – and the blessings of his patrons – like the aforementioned Henry VIII, whom one critic described as “one of the most tactful marketers of all time….and he did it about 500 years ago.”

Just as we peruse social media for tasty tidbits about celebrities we don’t know – but do judge – the hoi polloi of the 16th century obsessively consumed paintings, all of them artfully “Photoshopped” to make the subject look handsomer, more mysterious, more powerful, to underline the notion “I am mightiest of kings – or queens as in the case of Elizabeth I.”

According to one source:

“Modern historians have been able to compare various portraits of Henry with surviving clothing garments and amour. Based on this comparison, we know that Henry’s legs were much shorter, stomach was much larger, and health was much worse in reality than portrayed in his paintings…”

From Henry VII’s seizure of the throne in 1485 end the 30-year War of the Roses – the newfound unity symbolized by an heraldic emblem that combined the red and white rose which appears throughout the exhibition – to the death of his granddaughter Elizabeth I in 1603, the Tudor courts were cosmopolitan hubs, boasting the work of Florentine sculptors, German painters, Flemish weavers, and Europe’s best armorers, goldsmiths, and printers.

The lavish show traces the transformation of the arts in Tudor times through more than 100 objects— including the aforementioned iconic portraits, plus tapestries, manuscripts, sculpture, and armor, from The Met’s own collection and international lenders. Taken as a whole “The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England” proves beyond a doubt that in more ways than one the Tudors were the pop stars of the English monarchy, performing brilliantly in a daily soap of their own making in a world filled with false facts – like the VIIIth’s and Lizzie’s looks on canvas – to justify and ensure their legitimacy and legacy as powerful, but benevolent leaders.

By chance, “The Tudors” opened shortly after the death of Elizabeth I’s contemporary namesake Queen Elizabeth II, underlining the fact that art generally outlives the celebrities it serves.

Think Holbein and his peers.

Think Warhol and his Elizabeth (Taylor), also Marilyn, Mao and Elvis…

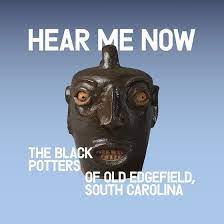

Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield South Carolina (though February 5, 2023):

Yes, the show is a tip of the hat to political correctness, nevertheless, it reveals true facts about decades before the Civil War, when a successful alkaline-glazed stoneware industry developed in the Old Edgefield district, a clay-rich area in the westernmost part of South Carolina.

From the beginning, enslaved African Americans were involved with all aspects of this labor-intensive industry. The stoneware they made — durable, impervious, utilitarian vessels of varying sizes and forms needed for food preparation and storage — supported the area’s expanding population and was inextricably linked to the demands of a lucrative plantation economy.

This show of unsung, but extraordinary artists features – rather, belatedly celebrates – sculptures, elegant and somehow modern, created by skilled, though heretofore unsung, African American artists.

That said, “Hear Me Now” is juxtaposed to artwork “Why Born Enslaved!” by the French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Created in 1868, 20 years after emancipation was realized in the French Atlantic, the sculpture made its debut in Paris against the backdrop of European colonialism, imperialism and the recent end of slavery in the United States.

“Hear Me Now” is summed up by the Met , paraphrasing as follows:

“…(The show) includes monumental storage jars by enslaved and literate potter and poet David Drake – or just Dave to his friends and fans – alongside rare examples of the region’s utilitarian wares, as well as enigmatic face vessels whose makers were unrecorded. Considered through the lens of current scholarship in the fields of history, literature, anthropology, material culture, diaspora, and African American studies, these 19th-century vessels testify to the lived experiences, artistic agency, and material knowledge of enslaved peoples.”

At The Met, Top Dog (Tudors) and Under Dog (Dave and his circle of artistic slaves) together tell quite a story about art for social change – and status.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.