31 Oct TIO NYC: “Straight Line Crazy” & “Cost of Living,” Straight Line Great!

As we continue our deep dive into New York’s cultural banquet, the following two plays entertained and enlightened.

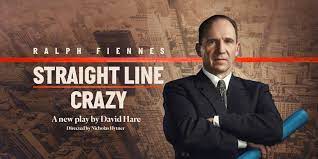

“Straight Line Crazy” at The Shed:

“Robert Moses was in it to build his dreams. You know, as a young man he did wonderful things, and his dreams were incredible. He would tell me these stories about thinking of the West Side Highway and Riverside Drive. And you’d sit there just in rapture—and you saw, this was a guy who had these great dreams, and when he’s young he doesn’t know how to accomplish that, because he’s an idealist. But he learns how to accomplish them by using power. And then he changes. So his dreams—I think I have a phrase like this in “The Power Broker”—were no longer for ideals but they’re for whatever increment power could give him,” explained renowned author Robert Caro in a New Yorker interview about the subject of his magnum opus “The Power Broker,” (1974).

Also the subject of David Hare’s play “Straight Line Crazy,” now up at The Shed and directed by Nicholas Hytner and Jamie Armitage.

The sold-out production features a sneering, snarling, charismatic Ralph Fiennes, who broods and rages with such panache we (almost) forgive his sins. In other words this portrait of the iconic power broker with clay feet and gluttonous demands is mesmerizing, an imperious Zeus raining thunderbolts down on the masses. The work of his supporting cast, 12 notable talents from across the pond, is equally strong and engaging.

If power tends to corrupt, as Sir John Dalberg-Acton, 8th Baronet once claimed, and absolute power corrupts absolutely, thanks to Fiennes and the ensemble it also entertains absolutely.

Hare’s drama is about two chapters in the long life of the visionary master builder and parks commissioner who, for 40 uninterrupted years (under 18 different US presidents, from Grover Cleveland to Ronald Reagan), was considered among the most powerful men in New York.

Moses saw wastelands that would become parks, bridges that would span rivers and bays, and a garland of highways and parkways that would weave the city and surrounds into one.

However, Moses was also a racist – a Jew who was an anti-Semite – who was contemptuous of the poor, and eschewed public transportation because that was for, well, the public, the hoi polloi. The man tore down tenements to make way for giant clumps of middle-income housing, including Kips Bay and Stuyvesant Town on the East Side of Manhattan. Fact is this modern-day Moses displaced about half a million people and wrecked neighborhoods to realize a vision on steroids.

Robert Moses, in short, both shaped – and misshaped– the New York some 20+ million people are still living in.

The first act of “Straight Line Crazy” takes place in 1926 when Moses is rising to power and planning to run a pair of parkways across Long Island, right through the estates of some of the richest men on earth, including Henry Vanderbilt.

The second act fast-forwards to 1955, when Moses is on the verge of driving a sunken highway through the center of Washington Square Park – and fails because groups of citizens organized against his schemes and the prioritization of cars over public transportation, campaigning for a very different idea of what a city like New York should be.

Great performances tricked out in a great production would be enough to carry the day, but “Straight Line Crazy” also works because the story is plugged directly into the energy system of the culture that birthed Moses – and others like him today who believe they are always right and the masses always wrong.

Note: According to one online source, the title of the play comes from a quote Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger – her family newspaper did more to shield Moses from public criticism than any other publication – gave to Caro for his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography.

Jesse Green’s review of the show for the New York Times follows:

I doubt I’d have enjoyed meeting the real Robert Moses, New York’s paver of highways, evictor of minorities, eminent domain eminence and all-purpose boogeyman. But it’s a huge pleasure to meet him, in the form of Ralph Fiennes, in David Hare’s “Straight Line Crazy,” which opened on Wednesday at the Shed.

Whether the creature Hare and Fiennes create has anything to do with the creature that created modern Gotham remains, for a while, an irrelevant question. Moses’ actual demeanor and utterance, as portrayed in the nearly 1,300 pages of Robert Caro’s biography “The Power Broker,” are little in evidence at the Hudson Yards theater.

Fiennes is too gloriously entertaining for that. Melodramatic in the old-fashioned sense, a hero or villain from an operetta or Ayn Rand, he crows his lines like a rooster, albeit in an accent suspended somewhere between East Anglia and Texass. With his nose pointing straight up and his chest pointing straight out, he’s a figurehead on the prow of a ship that can slice through icebergs as easily as red tape…

“Cost of Living” (at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, through November 6 only):

Winner of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize, Martyna Majok’s powerhouse play was hailed by The New York Times as “gripping, immensely haunting and exquisitely attuned.” “Cost of Living” is about pride in tension with our need for connection, about resentment yielding to resilience. The story is told through the lens of a former trucker and his recently paralyzed ex-wife and a wealthy, arrogant young man with cerebral palsy and his new caregiver.

The story line also touches on privilege, disability, and expectations, realized – or not. The experiences of these two very different couples ultimately converge in the meeting of two strangers (Eddie the truck driver and Jess, the former student) in a small, empty apartment in Bayonne, NJ.

Through clever (read revolving) scene changes the production alternates between scenes of Eddie (driver), Ani (ex-wife), Jess (caregiver) and John (privileged, manipulative student) that put front and center the physical realities of the daily life of the disabled. And Majok does not look away from even the most private interactions of this foursome. She shows us Ani in the bathtub getting soaped up (and more) by Eddie and John getting shaved and showered (equally perilous operations) by the no-nonsense, tough-talking Jess.

In the end, “Cost of Living” balances discretion with daring. Every naked – yes, in all senses of the word – moment is dramatically accounted for, but with great care for the dignity of the actors.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.