24 Apr TIO NYC: Devil in the Details! More Theatre & Dance!

We continued to forward march through the bounty that is New York’s Spring offerings: more about theatre and dance.

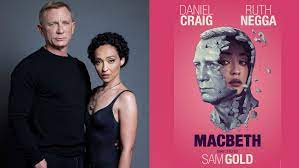

Sam Gold’s Macbeth at the Longacre Theatre through July 10:

Foul is no fair. Not after two years (and counting) into the Age of Corona and the divisiveness in our country dialed up to 11. Yet foul is in the air as the great Elizabethan Scribbler’s tale of malice, matrimony, murder and mayhem continues to have Big Moments.

Last fall in London Yaël Farber mounted his militaristic, modern version of MacBeth with James McArdle and Saoirse Ronan in the leads; Joel Coen’s barebones, bleak, black-and-white and brilliant “Tragedy of Macbeth,” kicked off last year’s New York Film Festival and then made its Apple TV+ debut.

In those and other versions of the Scottish play directors made their own kind of hay with the text, as Sam Gold does in his interpretation featuring supernovas Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga.

On the face of it Gold’s production has it all going on: two sexy stars, plus the eye of newt and toe of frog, tongue of a dog, etc. But it also has the coronavirus thing – and the curse.

Yes, the curse.

According to folklore – and online sources – Macbeth was cursed from the get-go. The story goes that a coven of witches objected to Shakespeare using real incantations, so they cast a dark spell on the play.

Legend has it MacBeth’s first performance (around 1606) was riddled with disaster. The actor playing Lady Macbeth died suddenly, so Shakespeare himself had to take on the part. Other alleged mishaps include real daggers being used in place of stage props for the murder of King Duncan (resulting in the actor’s death).

Other productions have been plagued with accidents, including actors falling off the stage, mysterious deaths, and narrow misses by falling stage weights, as happened to Laurence Olivier at the Old Vic in 1937.

And then it was Gold’s turn.

Sam Gold

According to The New York Times, Gold’s MacBeth had to cancel its April Fool’s Day performance minutes before curtain-up when a cast member tested positive. On April 2, Craig also tested positive and the show closed for 11 days. Then, on the Thursday, April 14, performance, its third after reopening, another member of the cast tested positive and all of the understudies were busy filling in.

As was the case the night we saw the production.

In fact the number of understudies having to step up prompted Gold to make a brief appearance just before the curtain went up. Alluding to the curse, Gold told the assembled we were going to be treated to “a very special performance” populated as it would be by so many talented replacements, including one so green we should not to be surprised by the fact she was still on book and would be holding a script.

In the end, the evening was more frustrating than it was special.

Frustrating in part because Gold succumbed to yet another curse of our time: wokeness.

Banquo, the general whose ghost famously haunts Macbeth, is played by a woman for one example, Amber Gray formerly of Hadestown, (who was lackluster). Malcolm, the son of murdered King Duncan, is Asia Kate Dillon, an actor who uses they/them pronouns, (also meh). And there are two interracial marriages, the Macbeths and the Macduffs.

Then there are the witches, about as threatening as Julia Childs – actually Julia is more intimidating – as they brew up toil and trouble on a cooking table. And where are we in this hurly-burly world, the black-on-black pipes on brick set straight out of Louise Nevelson? In one interview Gold alluded to a punk rock club.

Frustrating because gender fluidity and actors playing as many as three different roles meant at times it was hard to tell the players for the score card, a challenge that one hopes will be largely resolved once the A team is back on the boards.

And what the heck was that ending? The casts seated in a row on the stage eating soup or stew as one cast member, (who otherwise plays a witch), sings a folk song.

Huh?

Special in large part because, as the ultimate power couple, Craig and Negga, do not disappoint.

When we first meet Craig’s Macbeth the character feels grounded, approachable, even vulnerable. We instantly empathize with and root for this heroic soldier who saved Scotland and also happens to be a very happily married man in lust with his beautiful wife.

Craig also has the depth and control to make his decline and fall feel seamless and for the audience to ask why we were rooting for him in the first place. Because we were.

What’s more, Craig is able to demystify Shakespeares lines, delivering them in a plainspoken way and with such calm and conviction we feel as if it could be anyone of us up there on that stage. Craig as Everyman, never shaken, but stirring.

Negga’s complicated lived experience – she is the mixed-race daughter of an Irish mom and Ethiopian dad – is on full peacock on Macbeth’s stage, where she is making her Broadway debut. The fiery actress is able to portray the opposing tensions of her character in a way that makes her existential conflict wholly believable.

An exotic beauty, Negga is physically compelling (as her on-stage hubbie is handsome), but also confident and controlled when delivering her lines. Eye candy with a strong spine – until it bends under the weight of her profound, ultimately unbearable guilt.

With the charisma and conviction of the leads and the fact the plot is about a world turned upside-down just like it is today and a power trip gone south, Gold’s MacBeth is sure to catch fire. And a night of high drama helps to channel the rage many of us are feeling, with Shakespeare doing the heavy lifting.

Hangmen at the Golden Theatre, 252 West 45th Street:

Instead of a rage room, try the macabre madness of Hangmen for release and relief.

“Three Billboards” auteur Martin McDonagh penned the black-as-tar comedy starring Alfie Allen of “Game of Thrones” fame as the maybe murderer and David Threlfall as the Dickensian Harry Wade, the country’ second most renowned executioner. (Hence Hangmen, plural.)

We meet Harry in the opening scene of the play, set in a dank cell in 1963, as he secures a noose around the neck of a convicted young murderer who dies loudly protesting his innocence.

Two years later, the name of that man, Hennessy, comes up in the conversation at a pub near Manchester, owned by Harry’s wife Alice (a beleaguered, wholly believable Tracie Bennet). It is, as Harry puts it “a momentous bloody day,” when capital punishment was made obsolete in England.

Into the sodden mix of dullards walks a local journalist named Clegg looking for a money quote from the man who once oversaw the demise of hundred of sad souls. The besuited and bow-tied Harry is all too pleased to oblige.

Enter Allen’s Mooney, who follows Clegg through the door.

“…Pleased to meet you/Hope you guess my name/But what’s puzzling you/Is the nature of my game…”

Thanks Mick.

Bingo…

Mod, odd Mooney saddles up to the bar to creepily chat up Harry’s moping and plain-as- vanilla 15-year-old daughter Shirley (Gaby French, pitch perfect, inside and out).

What follows is devilishly funny – and not funny at all.

Hangmen slays.

For more, read this review from The New York Times.

Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents at The Met, through July 31:’

Winslow Homer’s “Gulf Stream, courtesy, The Met.

Winslow Homer regularly approached subjects overlooked by professional artists of his day – rural schoolchildren, hunting scenes, or the lives of recently emancipated African-Americans – with a passion for telling a good, if sometimes inconclusive story. And yes, while his signature painting is center stage in this wonderfully illuminating show, Crosscurrents.

The wide-ranging exhibition speaks loudly through many images, in all, 88 powerful oils and sparkling watercolors, the largest critical overview of Homer’s art and life in more than a quarter of a century. Images in this show beautifully depicts life in the 19th century, but also offers up universal ideas such as the primal relationship of man and nature. In fact, themes of mortality haunt Homer’s work, from those early Civil War paintings to his mid-career hunting series and, finally, his late studies of the power of Mother Nature embodied by the sea.

“Gulf Stream,” (1899), serves as a marker for how the curators— Stephanie L. Herdrich and Sylvia Yount in New York, Christopher Riopelle in London— see Homer in the 21st century. To quote The Atlantic, he is “No longer an oracle of American innocence, he is recast as a poet of observed conflict: North versus South, man versus sea, nature red in tooth and claw.”

“The Gulf Stream” depicts a sailor, placing a Black man center stage, far from cliched plantations and cotton fields. This protagonist is adrift on heavy seas in a dingy old boat with no rudder or mast. In the foreground, sharks slice through water in frenzy; in the background, a waterspout could also mean certain death. But there is also a boat in the distance, which could mean salvation. Which will it be? “Gulf Stream” proves that Homer is a master of what some critics have described as “ambiguous outcome,” a surrogate for the evanescence of life.

According to The Met, which co-produced the show with London’s National Gallery:

“This exhibition reconsiders Homer’s work through the lens of conflict, a theme that crosses his prolific career. A persistent fascination with struggle permeates his art—from emblematic images of the Civil War and Reconstruction that examine the effects of the conflict on the landscape, soldiers, and formerly enslaved people to dramatic scenes of rescue and hunting, as well as monumental seascapes and dazzling tropical works painted throughout the Atlantic world…”

Go here to The New York Times for an in-depth review of Crosscurrents in which critic Roberta Smith describes Homer as a “radical painter on the brink of modernism.”

20th Anniversary of Flamenco Festival at City Center:

Manuel Liñán has deservedly garnered international praise for his showmanship and the seamlessly engaging way he challenges the rules of traditional flamenco.

In VIVA! Liñánis joined by six captivating bailaores-bailarinas, male dancers dressed in traditional female costumes. In their jubilant expression of flamenco dancing the feminine is embraced by the masculine body and gender roles are broken, which brings to vivid life a dramatic new form.

New York City Ballet at Lincoln Center through May:

When the curtain went up on the mystical Serenade we found 17 women of the New York City Ballet bathed in a blue light, each with an arm extended upward as if reaching for the sky.

As the dancers turned away from the light, the orchestra played the slow opening chords of Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings. Serenade, by the company’s founding choreographer, George Balanchine, is a stirring work, elegiac and filled with wonder.

Serenade turns out to be a milestone in the history of dance. It is the first original ballet Balanchine created in America and one of the signature works of New York City Ballet’s rep. Balanchine began the ballet as a lesson in stage technique and worked unexpected rehearsal events into the choreography. A student’s fall or late arrival became part of the ballet.

After its initial presentation, Serenade was reworked several times. The form in which we were privileged to see the work was presented in four movements: “Sonatina”, “Waltz”, “Russian Dance”, and “Elegy.” The last two reverse the order of Tschaikovsky’s score, ending the ballet on a note of sadness – though the audience was in revelry.

Jerome Robbins built his reputation as a choreographer on his highly innovative movements structured within the traditional framework of classical dance. His unceasing inventive was on display inb his Goldberg Variations, a choreographic tour de force that pays homage to Bach’s epic score by unifying classical and modern movements in one monumental, virtuosic ballet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.