15 Aug Telluride Gallery: “Then & Now,” (until September 15)!

TheTelluride Gallery of Fine Art is pleased to present “Then & Now,” a group exhibition featuring artists Sheila Pree Bright, Dan Budnik, Alison Saar, and Lezley Saar. Join the gallery for a local Art Walk evening, Thursday, September 2, 500pm – 800pm. In town? Just stop by.

Alison Saar, Tango

In 1849, French writer Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr penned words that have rung through the ages: “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose “ (or “The more things change, the more they stay the same”).

Around the same time, a quip attributed to American author and humorist Mark Twain – “History doesn’t repeat Itself, but It often rhymes” – restates that universal truth.

The current show up at the Telluride Gallery (of Fine Art) neatly picks up those threads and runs with them..

Profound social, cultural, and political divisions that cracked open like Humpty-Dumpty in the Sixties— still threaten to tear American democracy apart. Among the challenges our country continues to face few have proven more wrenching than America’s foundational sin: slavery.

And the wedge of race which still cuts deep is on display at the Telluride Gallery in a show aptly titled “Then & Now.” The group exhibition features artists and activist Sheila Pree Bright, Dan Budnik, Alison Saar, and Lezley Saar, all exponents of art for social change (versus art for art’s sake, also a Sixties phenom).

As in Sheila Pree Bright who strives to give visibility to often-unseen communities. On view in the show are six photographs from her documentation of the 2020 response to police shootings in Atlanta, Ferguson, Baltimore, Washington D.C., and Baton Rouge.

Black Men Standing with brothers showing their solidarity suited up. A silent march Dr. Martin Luther KIng’s birth home marching on the historic street, Auburn Avenue, Atlanta, GA, 2020

Pree Bright’s work is all about capturing moments she feels we don’t see or moments that are different from the way traditional media portrays African Americans.

“As a Fine Art Photographer, I am interested in the life of those individuals and communities that are often unseen in the world. My objective is to capture images that allow us to experience those who are unheard as they contemplate or voice their reaction to ideas and issues that are shaping their world. In this process, what I shoot creates contemporary stories about social, political and historical context not often seen in the visual communication of traditional media and fine art platforms. My work captures and presents aspects of our culture, and sometimes counterculture, that challenges the typical narratives of Western thought and power structures,” quoting Pree Bright on her work.

The Peoples Uprising. Justice for Breonna Taylor, protesting the decision by the Kentucky grand jury to indict former officers in connection to the shooting death of Breonna Taylor, Atlanta, GA, 2020.

And yes, stating the obvious, shooting in black-and-white is a metaphor that underlines the historic quotes (above) about change. Or not much change (since the Sixties). The artist’s work connects the dots between the Civil Rights movement from that era and recent protests for social justice.

Go here for more on Sheila Pree Bright.

Another way to forge that connection would be for Sheila Pree Bright to hold hands with Dan Budnik. The highly acclaimed photojournalist was front and center in the heyday of the Civil Rights movement.

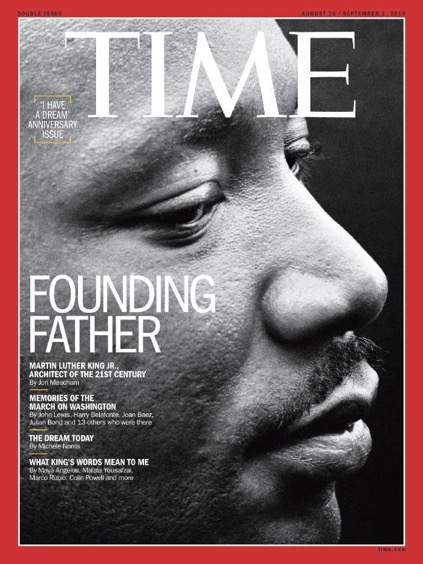

March on Washington, August 28, 1963: Martin Luther King, Jr. after delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech.

It was Budnik’s teacher, Charles Alston, at the Art Students’ League of New York, the first African American to teach at the League, who inspired his interest in documentary photography and the budding Civil Rights Movement.

Budnik went on to capture that slice of American history during his time working for Magnum Photo, professional home of other luminaries like Cornell Capa. In fact, he cleverly positioned himself right behind Martin Luther King in Washington, D.C. – all the other photographers were shooting him from the front – when King delivered his iconic ‘I Have A Dream” speech. In fact, TIME magazine chose Budnik’s now iconic portrait of King for its “I Have a Dream” 50th-anniversary issue in 2013.

Budnik’s career consisted of photo essays for leading national and international magazines, focusing on human rights, ecological issues and artists. He shot assignments for Life, Look and numerous other leading magazines, and his work was collected in several books, including “Marching to the Freedom Dream” (2014), which featured his pictures from three significant civil rights moments: the 1958 Youth March for Integrated Schools, the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the protest march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., in 1965.

Grade School Children waving to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and civil rights leaders, Oak Street, Montgomery, March 25, 1965.

“Dan Budnik’s portraits of fine artists intrigued me. I became motivated to dig deeper into their work and learn more about art history,” said Baerbel Hacke, former director, Telluride Gallery.

Go here for more on Dan Budnik.

The daughter of collagist and assemblage artist Betye Saar, Alison Saar perpetuates her mother’s legacy (and leitmotif): the marginalization of both women and minorities, particularly the African diaspora.

Cotton Eater II

Saar is among a larger generation of mark-makers who recognize the body as a site of identity formation, acknowledging historical injustices and presenting defiant figures that seem to transcend their pasts.

Referencing African and Afro-Caribbean art in her work, A. Saar often alludes to mythological narratives or rituals that fuel notions of history and identity. The woodblock prints on display at the Telluride Gallery, yes, recall the tragedy of slavery in our nation, but her figures also illustrate strength and resistance. In that way, the artist powerfully contributes to the narrative of the African American experience as one informed by history and heritage.

In general Alison Saar appears to be on mission to balance anger with beauty and optimism.

Go here for more on Alison Saar.

Lezley Saar comes from a family of artist and those familial relations – her father is also an artist – have had a huge influence on her work: to be able to create alongside her famous mother, sister and now daughter has been a privilege. And that is where the artist found much of her interest in feminist and African American legacies that morphed into her research on being biracial and themes of hybridity and identity, race, gender, beauty, normalcy, and sanity, her narrative work often inspired by literature or historical figures.

A Night at the Uranium, 2015 Acrylic on fabric on panel.

“I like the idea of a painting sucking you in like when you really get sucked in by a good book…I use that kind of metaphor as a vehicle for doing my art,” the artist explained.

Gender Is the Night, 2017 Acrylic on fabric on panel.

Saar’s works are primarily mixed media, three-dimensional, and oil and acrylic on paper and canvas.

Go here for more on Lezley Saar.

We sum up “Then & Now” with a quote by Zadie Smith from The New York Review of Books.

“What might I want history to do to me? I might want history to reduce my historical antagonist—and increase me. I might ask it to urgently remind me why I’m moving forward, away from history. Or speak to me always of our intimate relation, of the ties that bind—and indelibly link—my history and me.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.