04 Jan Telluride Gallery: Ed Moses +“Cool School,” Through 2/6!

Thursday, January 7 2021, marks the first Telluride Arts’ Art Walk of the New Year. The Telluride Gallery of Fine Art is continuing to feature a celebration of the late work of art world titan Ed Moses. A second exhibition – “Evolution of the Cool School: Small Works by Ed’s Chosen Family” – displays small works by a few of Mose’s close friends and colleagues, all part of LA’s “Cool School.”

For further information about Art Walk venues, go here.

WEB, Ed Moses at Telluride Gallery through 2/6/2021.

Two shows; one ethos: art is a mirror of life, that of the inner world of the maker, as well as his or her surroundings. It is also a map showing us possible paths out into a wonderfully nuanced universe where color, shape and composition are remarkably active and alive, a many splendored thing to behold and embrace – starting, in the case of the new featured shows at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art, with the paintings of art world titan Ed Moses. The work of other celebrated artists in Mose’s circle is on display in a coefficient exhibition in the newly renovated back room of the venue.

Blockbuster #1, Ed Moses : “Saving the Best for Last”

“These are all self-portraits.These paintings have history, action, scars and blemishes, scratches and imperfections. ‘Theses’ are me,” Ed Moses.

EdMoses, Oh 13

“Saving the Best for Last” is the culmination of Ed Moses’ seven-decade career as a world-renowned mark-maker. The exhibition showcases outstanding examples of the artist’s late work.

Moses is universally considered one of the foremost post-WWII abstract painters, celebrated for his ever-changing, highly exuberant approach to his art. The so-called “Master of Crazy Wisdom” adapted the jazz-like improvisation and freewheeling, muscular gestures that characterized the loose confederacy of artists known as Abstract Expressionists. As a spiritual descendent of that movement, Moses was all about the notion of the canvas as an existential “arena in which to act” (per art critic Harold Rosenberg), but he managed to introduce a West Coast sensibility to the idiom.

The exhibition is very personal to Telluride Gallery owner Ashley Hayward. Moses was a dear friend of the family.

Ashley first met Ed Moses – or he her – when she was a babe in diapers, a simple fact which opens the door to the history of the LA’s modern art scene in which her father, James Hayward, has loomed large for most of his 70+ years. (Hayward claims to have started painting at age four.)

That story also explains the subtext that underlies every one of the major shows at the Telluride Gallery since Ashley and husband Michael Goldberg took over the venue from its original owners in January 2017. Since then, most of the exhibitions in the space have honored at least some of the major Left Coast artists in the Haywards’ orbit – including James Hayward himself.

“My father’s circle, California artists of all stripes, respected one another. Our family friend, critic David Pagel, described the LA scene as completely unique in that artists from all walks of life came together to support one another’s work. There were no boundaries. These late paintings of Ed’s are the crescendo of a lifetime of work. The freedom he discovered in the world he dominated vibrantly shines through. Ed was fearlessly creating until the end,” said Ashley, who noted the man was still going at it with gusto (from his paint-splattered wheelchair) two weeks before his death in January 2018.

Ed Moses, Woop1

The artistic odyssey of Ed Moses is the stuff of art world legend, his flights of fancy combining as they did self-exploration, daring, irreverence, and self-confidence (tempered with an authentic humbleness).

Having served as a surgical technician in WWII, Moses came to painting after washing out of a pre-med program. In 1949, he enrolled at UCLA where he met Walter Hopps of Ferus Gallery. He impressed Hopps to such a degree his thesis exhibition was staged in the clean white cube that was Ferus’ space. The stable ultimately included Moses as Top Dog along with the likes of Ed Kienholz, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston, John Altoon, Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha, all good-looking, hard-living, hard-drinking surfers, beatniks and lovers of women, whose work was a stylistic combo of Pop, hard-edged or geometric abstraction and minimalism.

That first exhibition cemented Mose’s place as a founder of LA’s red-hot “Cool School.”

Not content, however, to adhering to a single style or movement, Moses coined the nickname “the mutator,” pointing to his ever-morphing body of work. Shunning terms like “creative” or “artist,” he preferred to be described simply as a “painter.”

Later Moses later went so far as to say:

“I don’t make paintings, I find paintings,” speaking to the importance of process in his non-stop evolution in terms of giving up all attempts at controlling confusion instead learning to be in tune with it, to swing with it.

“There’s some vague thing I’m shooting for, but I don’t know exactly how it’s going to come about. So I try one thing and then another and, in this process, once in a while something falls into the cracks.”

EdMoses, Fruitbar 3

Moses likened his modus operandi to the work of a shaman: interpreting the unknown through symbols, objects and mark-making.

In 1978, Moses converted to Buddhism, which pushed his experimentation even further, strengthening his relationship with chance and experimentation and lessening his reliance on control and restraint.

According to art critic and lifelong friend, Frances Colpitt, it was as if “…the brush were an extension of his arm and body, and the paint a bodily fluid. This bionic relationship to his tools and materials is plainly evident in the finished and ever fresh paintings.”

In an interview just before his death, Ed Moses talked about being terrified that he was going to disappear into “some invisible zone.” His hedge? Simple: Leave ever-evolving marks on canvas like the cavemen who left handprints on cave walls, each painting standing as a totem to Moses’ illuminating “non-journey.”

James Hayward suggested his friend’s attraction to Buddhism had to with the dharma of non-judgment and and non-attachment, which boils down to the ability to walk freely between attraction and aversion, likes and dislikes, praise or blame, without attaching to one side or another, and without being jerked this way or that.

And without being attached to any particular outcome.

To that point, Ed Moses’ son Andy, a prominent artist in his own right, was quoted in several obituaries as saying of his dad:

“He never ceased to push the envelope and he stayed engaged in painting every step of the way. He was a true explorer, able to pull it off every time. Most artists sort of struggle through transitional periods, but he didn’t have any transitional periods. He would abruptly stop one body of work, start another and have it fully realized.”

True even to the 11th hour before his death.

Ed Moses, OH1

“My painting is the encounter between the mind’s necessity for control and it’s yearning to fly…,” the artist once summed up.

“Throughout the seven decades of his career, Moses’s high-decibel color sense continued to develop. Rarely tonal or modulated— except to the extent that a swipe of the squeegee or brush pulls rainbows of contrasting hues across the surface—his colors are brash and jarring: pink and orange, turquoise and lime green, or lemon yellow and magenta. His colors grew more saturated and intense, his application of them more impulsive and urgent, evoking ever deeper emotional resonance. As his life progressed, Moses felt a strong kinship with shamans and prehistoric cave painters. The raw vigor of his process combined with the dark mysteries of the painted caves came to fruition in this last body of work,” added Frances Colpitt.

Summing up this work: Mose’s creations are largely pure color with only a hint of form running through the compositions, suggesting alien landscapes that tilt psychedelic.

“Saving The Best For Last” is an exhibition of 24 paintings and six digital pigment prints by the late artist Ed Moses. The paintings will be on view at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art from December 15, 2020 – February 6, 2021. The collection includes some of the artist’s last acrylic paintings, as well as digital prints provided by Patricia Correia Projects.

Ed Moses, more:

Ed Moses joined the art faculty at UC Irvine in 1968, taught at UCLA, the Skowhegan School of Painting, Cal State Bakersfield, and Cal State Long Beach. In 1976, he was granted a fellowship by the National Endowment for the Arts.

In 1980, Moses was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship and, in 1991, he won a place in the Whitney Biennial. In 1996, the Museum of Contemporary Art honored the artist with a major retrospective of drawings and paintings

In addition to his lengthy affiliation with the Ferus Gallery, Moses has has gallery exhibits worldwide. His work is also included in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art; the Denver Art Museum; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Musée National d’art Moderne – Centre Georges Pompidou; the Museum of Modern Art in New York; and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, among many other prestigious institutions.

Blockbuster #2: “Evolution of the Cool School: Small Works by Ed’s Chosen Family”

In alphabetical order the list of Ed Mose’s professional colleague and friends, their work on display at the Telluride Gallery’ back room, includes Charles Arnoldi, Edith Baumann, Larry Bell, Tony Berlant, Sue Dirksen, James Hayward, Scotty Heywood, John Miller, Andy Moses, Gwynn Murrill, Peter Shelton, and special candid images from Alan Shaffer of Ed and his friends over the years.

“These artists were all close to Ed throughout his lifetime. By bringing this selection of works together, we hope to honor Ed and his enduring influence and spirit,” said Ashley Hayward.

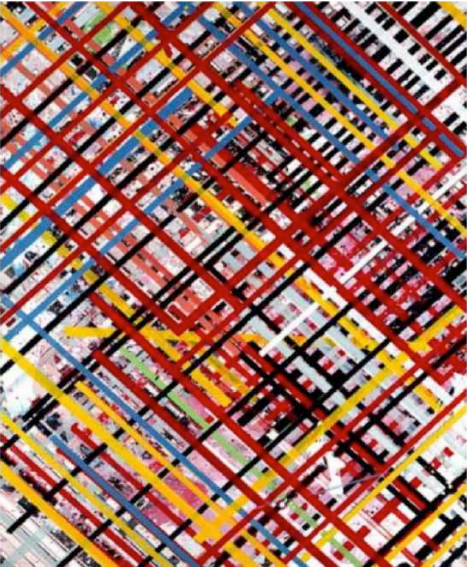

Charles Arnoldi is an abstract painter, sculptor and printmaker who has been making his mark (literally and figuratively) for over four decades, first achieving major acclaim in the 1970s.

CharlesArnoldi, Untitled.

Proof of his iconic stature, the artist’s work has been on display across the nation and abroad, notably in shows at Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum and New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Today, Arnoldi’s images can be found in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, among other prestigious institutions.

For what became his signature style, a boldly graphic and colorful aesthetic, Arnoldi employs a wide range of abstract visual language, from hard-edged geometric compositions to lyrical line works.

In the introduction to a survey of Arnolid’s works on paper, essayist Bruce Guenther noted:

“Arnoldi has always moved fluidly from drawing to sculpture, printmaking to painting, through a practice of continuous experimentation which has audaciously challenged the limits of media and the expectations of the viewer…”

“The goal is to make an inanimate object have a life of its own,” said the artist.

Originally from Ames, Iowa, and based in Southern California for 40+ years, Edith Baumann has interpreted the abstracts patterns she observes in the natural world. Her compositions tend to read as methodical, and yet no single element is perfectly controlled— Baumann allows the organic to interrupt her order. She describes “randomness and structure (as) two different things, happening at the same time, interconnected.”

Edith Baumann, Pattern Recognition 27.

Larry Bell is a sculptor and painter whose impressive body of work can be viewed across a single developmental arc of improvisation, experimentation and impulse – very much like the arc of Mose’s career though with a very different, much less “noisy”(read in your facce) outcome.

Larry Bell, Fraction

“I consider my work to be evidence of my studies and the externalization of a current thought,” Bell once told Ocula magazine.

Bell launched a successful career as an AbExer, who incorporated simple geometric forms and pieces of glass and mirrors into his action paintings, making highly touted, spatially complex collages,

That experimentation with surfaces eventually allowed the artist to fully explore the rich relationship between light and what it touches – such as in Bell’s signature Minimalist sculptures, transparent cubes at the nexus of shape, light, and environment.

The “will to form” is a principle in art history that suggests the guy or girl can’t help it: artists are physically and emotionally compelled to do what they do. As long as he has worked as a professional artist, namely over six decades, Tony Berlant has described the necessity to make art as a “basic human thing” dating back to “primitive” or “early man,” sharing that affinity with his friend Ed Moses.

Tony Berlant, HomeRun

Unlike conventional mixed-media pieces created from cutouts of random images from magazines or photographs and taped or glued to a surface, Berlant works with photo-printed metal (using the artist’s own images, plus vintage and modern metal signage and graphics) and found tin, which he fastens to panels with shiny steel nails, surrogates for his thumb print. The end result is a hybrid that lies at the intersection of painting, sculpture and photography, also Pop art (for its appropriation and elevation of everyday objects), assemblage and abstraction.

The work is, at once, all of, yet none of the above: Berlant is his own “ism.”

“In these deliciously complex combinations of abstraction and representation, paths appear (and vanish), positive and negative space shift positions, fragments coalesce, patterns form (and disintegrate), and surfaces become spaces (and vice versa). Nothing stays the same. Everything changes. Including you,” wrote critic David Pagel.

For painter Sue Dirksen, it’s all about light.

“When painting I allow intuition to guide me and use the brush as an extension of my arm — to bring forth luminosity and potently-hued energy. I am a colorist who meticulously builds up the painting with thin layers of acrylic wash — often into the hundreds — to embody the varying intensities of light/color. When experienced from different points of view, the paintings pulsate as the subtleties of light change to create a vibrant, impeccable, living surface.”

Dirksen began her studies in art in Japan with a sumi-e master, who taught her to empty herself of the external world and focus on the perfection of the brushstroke, repeating it until she caught its essence. Her work has always been concerned with the strong tradition of articulating light along with her desire to create impeccable, textured surfaces in her work.

Non-objective (non-representational) abstract art reshapes the natural world for expressive purposes and derives from, but does not imitate a recognizable physical subject or impulse. James Hayward is a world-renowned non-objective painter, also a celebrated art historian, and teacher.

Hayward had his first solo show in Telluride in the summer of 2017 and curated two blockbuster exhibitions for the gallery (“Objective Painting” and “Non-Objective Painting”) that same year. Personally he has made marks abstractly since the 1960s.

It all began for Hayward when, at age seven, he won a Smokey the Bear drawing contest – but soon discovered he was not so good at drawing people. Since then, the painter has won countless laurels for his hard-edged abstractions.

He has had shows at major museums including the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Gallery shows have included Roberts & Tilton in L.A.; Peter Blake in Laguna; and Modernism in San Francisco. In 1984, James Hayward also won a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship to work in Japan, a trip that triggered the artist’s move from flat blocks of color to thickly painted (mostly) monochromes.

Hayward’s work initially appears to be monochromatic, but reveals itself to be so much more upon close examination. The artist builds up his canvases with thick layers of oil paint using a grid structure and treating every mark as equally valid so the work appears to have no beginning and no end. Impasto became the artist’s signature in the 1980s, but despite his built-up surfaces, his images do not read as being about process alone.

“I would describe my dad’s paintings as visual meditations,” explains Ashely Hayward. “The mind gets lost, while the eye dances across the surface. It’s amazing to me how his works continue to reveal themselves to the viewer the longer he or she stands in place and observes. I have literally seen people transformed in amazement in front of Jimmy’s paintings. I understand that reaction. First you are struck by the beautiful, bold, heavy impasto brushstrokes, then the subtleties of the colors consume you. Finally you get lost in the rhythm of the marks, then more color variations and the play of light and shadow take hold. Truly a symphony for the eye and a delight to experience.”

With Scot (or Scotty) Heywood, think hard-edged and squeaky clean, his work all about art for art’s sake, not for the sake of recording a familiar reality or social commentary.

Scot Heywood, Double Edge

Born in Los Angeles, Heywood has pursued a course of non-representational, geometric abstract painting for more than 30 years. A self-taught artist, his works are indebted to the origins of geometric abstraction in such artists as Kasimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, though he has crafted a thoroughly personal interpretation. Heywood’s attention to detail and presentation are evident in the careful placement of individual panels, as well as the refined diagonal layering of paint.

As one of his gallery’s stated about the artist’s work:

”The viewer would be mistaken to consider Heywood’s paintings to be standard examples of the minimalist monochrome. His work invites extended contemplation, and engages with viewers on visual, physical and conceptual levels. “

David Pagel of the Los Angeles Times has written about the experience of viewing a Heywood.

“To stand before one of these paintings, each of which is the size of a generously scaled doorway, is to find your whole body involuntarily adjusting itself to the subtly out-of-whack geometry of Heywood’s art.

James Hayward curated a show at the Telluride Gallery in 2017 titled “Non-Objective.” It was dedicated to the memory of one of the artists in the show, John M. Miller, who passed away during the planning stage. According to the catalog, Miller’s hard-edged, abstractions helped shape the story of Los Angeles Minimalism.

John M. Miller, RED

In the early 1970s, Miller abandoned figurative painting and stripped his work down to its essence, which, for him, took the form of angled, colored bars repeated across the picture plane. He painted those bars—in shades of white, black, blue, violet, red, yellow, and green acrylic – on unprimed canvases, ranging in scale from intimate to all-encompassing.

Meticulous and meditative, his compositions have been variously categorized as Op Art and geometric abstraction and compared to the works of Agnes Martin and Brice Marsden,.

Miller’s work requires and rewards the viewer’s slow attention. As a spectator it is important to command your eye to perceive rhythmic movement in the interplay of the bars, opening the mind to their various associations: weaving, stitching, or a freshly raked Zen rock garden.

Andy Moses: Like father, like son?

Andy Moses, Geodesy.

Moses père painted with an insatiable passion that spanned seven decades, from the late-1950s until just weeks before his death at the age of 91. As described above, Ed Moses was endlessly intrigued by the metaphysical power of his art, creating works about the expression of temporality, process, and presence and remarking at one point that “The point is not to be in control, but to be in tune.”

Son Andy has been described as “a quintessential Los Angeles artist.” A graduate of the California Institute of the Arts, he has been exhibiting his work for over 30 years.

Moses fils has long been working in pure color, the forms in the work suggesting the nexus of abstraction and landscape. Since 2003, he has produced colorscapes in the vein of Rothko, a tip of the hat to mysterious, foreign worlds – including internal.

According to one online source, as an adolescent, Andy Moses watched Stanley Kubrick’s classic, “2001: A Space Odyssey” on the massive, curved screen at LA’s Cinerama Dome, an immersive experience that ultimately informed his concave canvases.

“I want them to refer to landscape without becoming landscape,” he once explained.

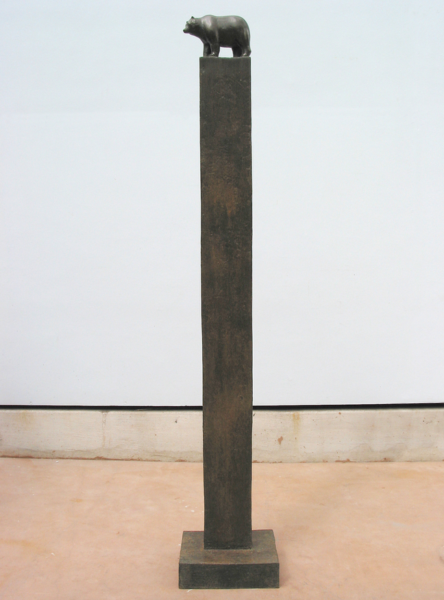

Sculptor Gwynn Murrill, who has been fashioning animals since the 1970s, studied as a young woman with some of the giants of the Sixties California art scene: Tony Berlant of intricately detailed, riotously colorful collage fame; Richard Diebenkorn of the iconic Ocean Park series of geometric abstractions of an urbanscape; and minimalist John McCracken. But it was the beauty and delicacy of Donatello’s “David,” which Murrill saw at the Bargello in Florence when she was a student at the American Academy in Rome, that turned the tide for the formative sculptor.

The splendid bronze portrait of a young David triumphantly stepping on Goliath’s severed head while holding a sword, anchored by the negative space around it, became a kind of muse for Murrill, who believes the space around and between her primary subjects are artistically relevant and very important shapes – and that includes her pedestals.

Peter Shelton (with thanks to the Getty Museum):

Peter Shelton, Ghosts

Peter Shelton’s sculptural practice encompasses a diverse range of themes, approaches, and media. Creating both large-scale installations and modest objects that may be held in the hand, Shelton draws from a vocabulary both figural and abstract, anatomical and architectural.

Born in Troy, Ohio, his family moved to Tempe, Arizona, when Shelton was a young child. After receiving his BA from Pomona College in Southern California in 1973, he returned to Troy where he attended the Hobart Brothers School of Welding Technology and worked as a welder for several years.

Shelton eventually returned to Southern California and received his MFA from UCLA in 1979. While there he began creating ambitious installations combining recognizable elements with highly abstract forms. These pieces were often layered and carefully organized in space – a visual strategies that became an essential feature of Shelton’s art.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Shelton concurrently produced both large-scale environments and more modest figurative pieces. Though his career has had no straightforward linear development, reference to the human form unites all of his work. A skilled craftsman, Shelton’s materials have included steel, bronze, cloth, cement, wood, paper, and fiberglass. He has also used water in several sculptural projects.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.