28 Aug Telluride Gallery of Fine Art Sept.: “Works on Paper,” A Group Show!

Thursday, September 3, 2020, marks the 4th Telluride Arts’ Art Walk of the season. Meanwhile up now and through mid-September the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art is featuring a blockbuster of a group show titled “Works on Paper.”

For further information about Art Walk venues, go here.

A young Charles Arnoldi at work.

Celebrated Paul Klee’s “Pedagogical Sketchbook,” a summary of over 4,000 pages of lecture notes from the Bauhaus school, begins with the oft-quoted “Take a Line for a Walk.” Translation: a point can become a line, a line can become a plane, and so on. However it evolves into a work on paper, an inspired line should reveal an artist’s strong intention and attention.

Bottom, urr, line, as art critic Robert Hughes once noted: “Art is invention, but also remembering.”

Case in point the the kaleidoscope of eye-popping art now on display at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art in a show titled “Works on Paper.” This blockbuster is mix of “isms” and mediums, styles and techniques, including the gestural abstraction of Charles Arnoldi and Lisa Pressman; the Surrealism of Edwina White; the mixed-media photography of LeAna Clifton and Caleb Cain Marcus; and the 3D Pop collages of Kelley O’Connor.

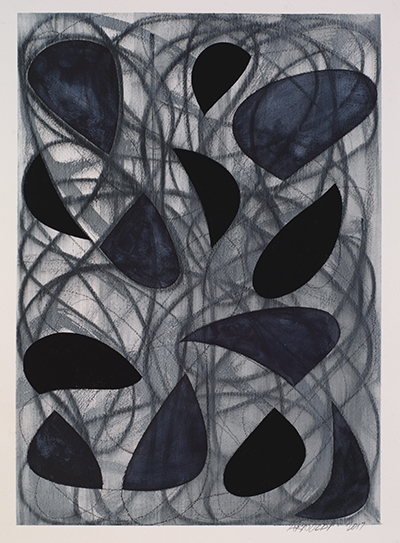

Charles Arnoldi is an abstract painter, sculptor and printmaker who has been making his mark (literally and figuratively) for over four decades, first achieving major acclaim in the 1970s.

Proof of his iconic stature, the artist’s work has been on display across the nation and abroad, notably in shows at Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Today, Arnoldi’s images can be found in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, among other prestigious institutions.

For what became his signature style, a boldly graphic and colorful aesthetic, Arnoldi employs a wide range of abstract visual language, from hard-edged geometric compositions to fluid, lyrical line works.

In the introduction to a survey of Arnolid’s works on paper, essayist Bruce Guenther noted:

“Arnoldi has always moved fluidly from drawing to sculpture, printmaking to painting, through a practice of continuous experimentation which has audaciously challenged the limits of media and the expectations of the viewer. But drawing has been at the core of Arnoldi’s work since the late 1960s.”

“The goal is to make an inanimate object have a life of its own,” said the artist.

“The two different bodies of work by Charles Arnoldi in the Telluride Gallery’s latest group show explores a breaking away from linear form and an experiment with curvilinear gesture and the interplay of positive and negative space,” observed gallery co-owner/curator Ashley Hayward.

(Go here for more on Charles Arnoldi.)

Some think of works on paper as a prologue to a Big Event like a major painting, but using the esteemed Arnoldi as one strong example, in the aggregate the Telluride Gallery’s “Works on Paper” is not a collection of scales and arpeggios, but finished compositions, complete and captivating unto themselves.

A second example, with a wink to Hughes, the invention and remembering of LéAna Clifton.

Cardinal Obsession, Clifton.

Clifton is drawn to large fields of color and contrasting line. For the past six years, the artist has focused, almost exclusively, on creating small- and large-scale abstract images of freight trains running through the far west Texas high-desert, capturing their visceral power and movement through color and contrasting lines, using paint and pencil towards dramatic ends.

I’ll have a Neoplotan, please, Clifton.

Clifton was exposed to art and photography at a young age and, through that discipline, she discovered a portal through she could reimagine and remix the world on her own terms. The camera became her communicator – and her escape. As she progressed in her craft, Clifton’s images became less definable, more abstract and also more beautiful. Increasing visceral, her new pieces distill the key elements of her composition down to the real nitty-gritty: light, form, color, movement and time.

and then she was gone, Clifton.

(Go here for more on LeAna Clifton.)

“You don’t take a photograph; you make it,” explained Ansel Adams.

Brief Movement, Marcus.

A third example, the invention and deep remembering of Caleb Cain Marcus, whose enhanced photographs are described by one critic this way:

“The markings seen in this series of images were supposedly random, but did not feel like it. Much like Anastasi’s drawings, Cain Marcus’ images echo automatic drawings attesting to the artist’s lack of control… which brings us back to the nature of death and life and the seemingly random influences of how and where they will touch all of us.”

Increasingly abstract, Caleb Cain Marcus’ work has always had a dreamlike quality that transcends mere reportage to reveal something new about place and time.

The artist enhances his photographs with layers of paint, creating an even deeper, more compelling image, the direct result of his belief that evocative colors deepen our understanding of the universe, internal and external.

Brief Movement, Marcus.

Particularly, though not exclusively, in this body of work, Marcus has dismantled the building blocks of visual processing, eliminating perspective and scale and the narratives those variables suggest. In the end, he has effectively given physical, visible form to whatever is left that dissipates into thin air and the Original Source following death. The images then function like visual force fields: while grounded in the natural world, they capture and contain spiritual energy.

“The work contains equal parts confidence and doubt. Thats what keeps you going,” said Arnoldi about his own art. The statement also applies to Marcus’ mystical, magical images.

Brief Movement, Marcus.

(For more on Caleb Cain Marcus, go here.)

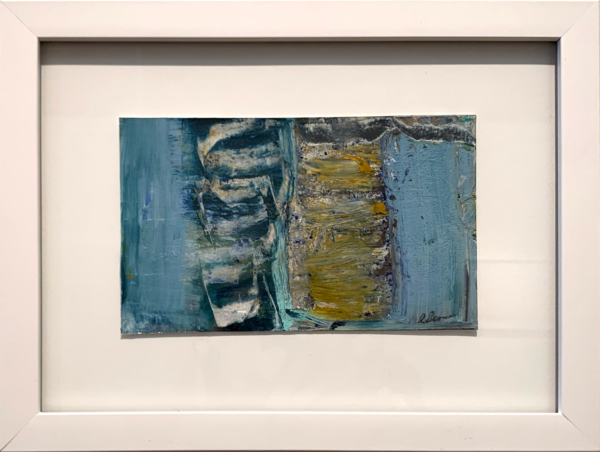

In the art for art’s sake camp (as opposed to art for social change), Lisa Pressman creates mixed-media works using oils, collage, wax, whatever to make muscular AbEx 2.0 images that express the landscape of her soul in the moments of creating. Her paintings leave an open invitation to explore that untraveled world with her.

“These works are viewer finished. Your participation finishes the painting,” remarked Arnoldi, again about his own images. But his observation applies to Pressman’s work – and frankly, across this show. (And shows that will follow.)

(For more on Lisa Pressman, go here.)

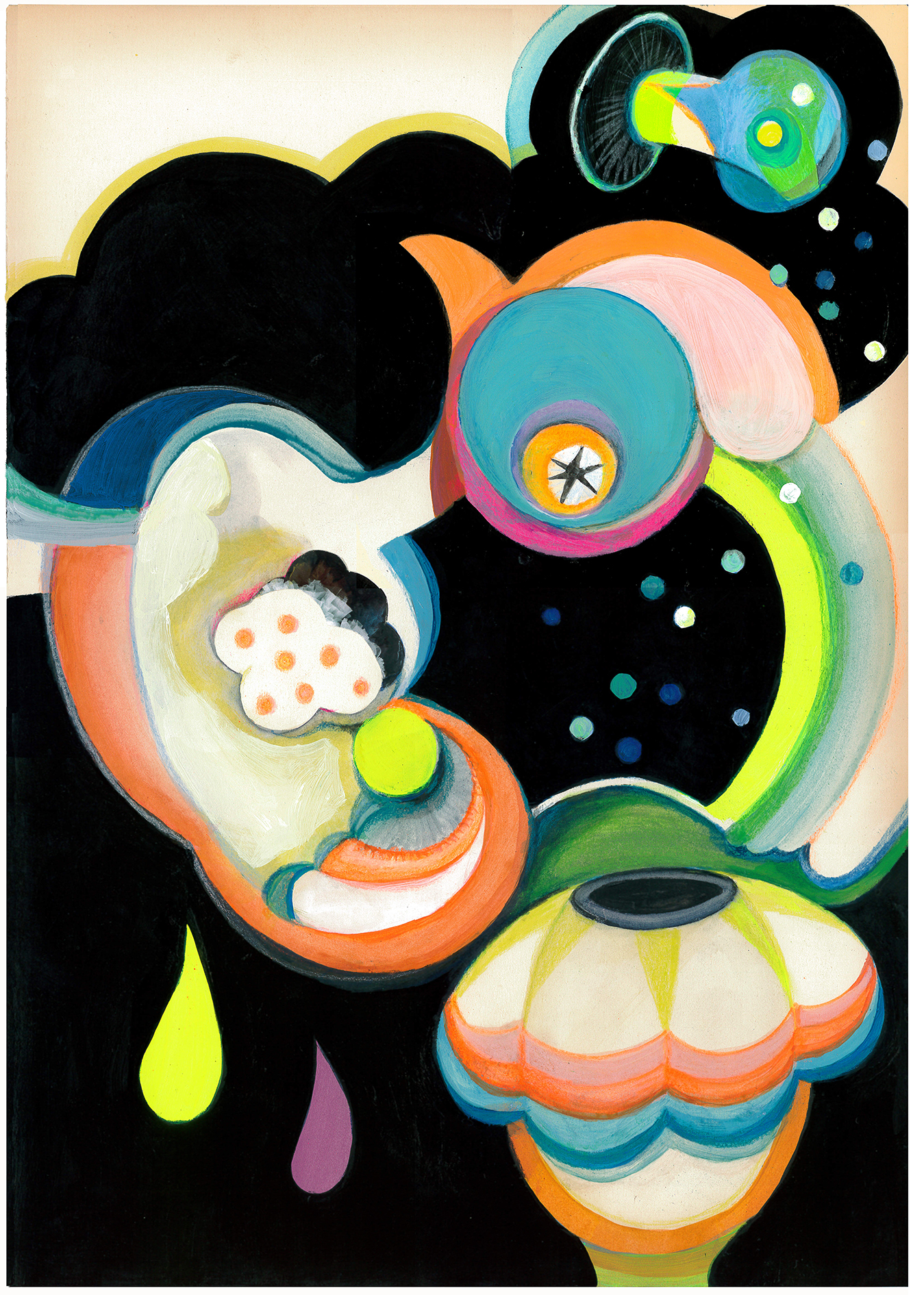

Primavera, White.

A goal of Surrealism was no less than revolutionizing the human experience, eschewing the rational, while promoting the value of the unconscious and our dreams. The movement of poets and artists found their muses in the unexpected, the uncanny and the unconventional. Surrealist icon Rene Magritte put it this way: “I intend to restore the familiar to the strange.”

Clementine, White.

Welcome to the wacky, wild, wonderful world of Edwina White, an Australian artist now living in Brooklyn, New York:

“Playful yet spooky, the faux-innocent art brut method preferred by Edwina White not only makes for compelling images, but also invites the viewer to search them for hidden meanings. White revels in being swept up by the challenge of making her ideas concrete,” wrote one art critic about White’s fictionalized portraits and whimsical vignettes.

Fissure

(Go here for more about Edwina White.)

Dorothy I, O’Connor.

Kelly O’Connor is a latter-day Pop artist, whose medium is collage. Her work is all lifting society’s veil to reveal the truth, be it daylight erotica, gaudy commercialism, and/or disposable everything (including people).

Mammoth 2018, O’Connor.

New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl sums up O’Connor and other works of social commentary best (in a Pop review from 2003):

“The goal in all cases (of Pop art) was to fuse painting aesthetics with the semiotics of media-drenched contemporary reality.”

Valley of the Dolls Avon Lady, O’Connor.

(For more on Kelly O’Connor, go here.)

Summing up, the latest Telluride Gallery group show is a collection that speaks to the poetry of witness of each artist, each one speaking in a different, but equally compelling language.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.