02 Sep September Art Walk, Telluride Gallery: Hayward & McCleary, Soft Opening This Week!

Telluride Arts’ First Thursday Art Walk is a festive celebration of the art scene in downtown Telluride. Participating venues host receptions to introduce new exhibits. The September Art Walk takes place Thursday, September 5, 5 – 8 p.m.

Gallery 81435 features Fawn Atencio in her solo exhibit, “Selected Territories,” on display through the month of September 2019. Atencio has recently been exploring how we connect to land as a form of identity. “I am interested in how places tell stories, create memories, and transfer meaning,” says Atencio. Growing up in Colorado, her grandparents were avid fishermen and women who, year after year took Atencio and her siblings to explore, fish, and camp in the Rio Grande National Forest. “The landscape seemed very magical to me as a child. It wasn’t until I spent an extensive period of time Asia and northern Africa as an adult, that I realized how much of my identity is formed by the American Western landscape.”

Telluride Arts HQ brings back (just in time for the Telluride Film Festival) multi-media artist (illustrator, animator, painter, sculptor and character designer) Dave Pressler for a show of his latest body of work. Over the past 20 years, Pressler has designed characters and worlds for such companies as Kid’s WB, Disney, Fox Kids Network, Wild Brain, and The Jim Henson Company to name a few. In the last decade, he shifted his focus to the universe of TV animation, where he has co-created and designed for the Emmy-nominated “Robot And Monster” for Nickelodeon. Most recently, Pressler art-directed “Boss Baby Back In Business” for Dreamworks TV. Pressler’s spirit of exploration and adventure is more than just Earthbound; he intends to be the first animator in space and currently holds one of the few passes to travel to space with Virgin Galactic.

MiXX Projects + Atelier is featuring a show of the work of California-based artist/philosopher Lisa Swerling, who crafts tiny sparkling worlds in little white boxes, thought-provoking, at times laugh-out-loud funny and always emotionally nuanced vignettes. Among her dioramas is a series that riffs on favorite films from yesterday (“Vertigo” and “Fargo”) and closer to today (“Free Solo”). Not to be missed

Slate Gray Gallery presents the abstract paintings of Sarah Van Beckum, which the artist describes as either personal “celebrations” or “soul tantrums.” (Podcast with the artist coming up later this week.)

And the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art displays the work of LA-based art titans James Hayward & Dan McLeary. The soft opening was August 24. The hard opening takes place in concert with Art Walk on Thursday, September 5. Please scroll down for more and to watch a video of both artists in action.

“Good artists see better than we do,” art critic Dave Hickey

To set the table for the latest ground-breaking show at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art, we begin with a few definitions and the simple understanding that all art is an adventure, offering up the gift of discovery to the eye and to the imagination. And, in the hands of master creatives like James Hayward and Dan McCleary, two long-admired Los Angeles painters, the canvases on display are redolent with the magic that is residual in all of us, like a favorite childhood rhyme.

Hayward is a renowned non-objective painter; McCleary, also a titan in the art world, paints realistic figures. His work is objective.

Non-objective (non-representational) abstract art reshapes the natural world for expressive purposes and derives from, but does not imitate a recognizable physical subject or impulse.

Objective art is work that depicts easily recognizable subject matter. It is also known as representational or figurative art.

Those definitions work well as entry points, but are limiting. In bringing Hayward and McCleary together, the exhibition at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art pushes the conversation about painting beyond abstraction and figuration—that longstanding, often limiting binary—into a sphere in which visceral sensation trumps genre. What’s more, the careers of both artists are distinguished by the brilliance, authority, insight, and wit with which they approach their work. The painters also align by prioritizing moments and gestures over narrative. As critic David Pagel writes in his essay for the exhibition’s catalog, the two men traffic in “stillness—and elusive, fugitive perfection.”

James Hayward, more:

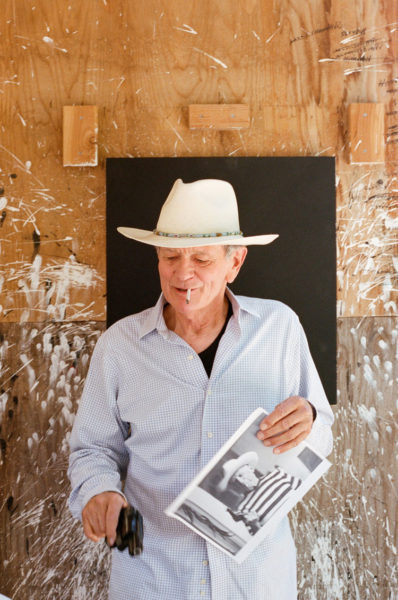

Artists, like cowboys, live an edge life somewhere between hard, isolated, isolating work, and the mythology that surrounds that whole daggum picture. For James Hayward that goes double: he is both cowboy and artist.

Folks generally find Hayward tricked out in full regalia – hat, boots, tired jeans, a burning joint hanging from his lips. Truth is his family has been breeding Arabian horses since the early 1970s, first in Bellevue, Washington, then on a big spread in Moorpark, just north of the City of Angels. Hayward’s home on that property is modest to say the least: an aluminum trailer, plus a studio and office/storage space for work.

The celebrated artist, art historian, and teacher is also the father of Ashley, co-owner (with husband Michael Goldberg) of the Telluride Gallery. Hayward had his first solo show in Telluride in the summer of 2017 and curated two blockbuster exhibitions for the gallery (“Objective Painting” and “Non-Objective Painting”) that same year. Personally he has made marks abstractly since the 1960s.

It all began for James Hayward when, at age seven, he won a Smokey the Bear drawing contest – but soon discovered he was not so good at drawing people. Since then, the painter has won countless laurels for his hard-edged abstractions. He has had shows at major museums including the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Gallery shows have included Roberts & Tilton in L.A.; Peter Blake in Laguna; and Modernism in San Francisco. In 1984, James Hayward also won a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship to work in Japan, a trip that triggered the artist’s move from flat blocks of color to thickly painted (mostly) monochromes.

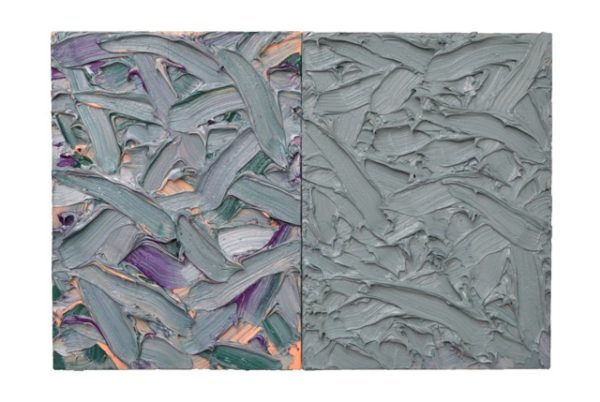

Hayward’s current exhibition at the Telluride Gallery features a selection from his “Abstraction” series, thick paintings that initially appear to be monochromes, but reveal themselves to be so much more upon close examination. Hayward builds up these paintings with thick layers of oil paint using a grid structure and treating every mark as equally valid so that the work appears to have no beginning and no end. Impasto became the artist’s signature in the 1980s, but despite his thick, built-up surfaces, his images do not read as being about process alone.

In “Abstract #244” (2017), arching indentations move across every inch of an all-white painting; shadows caused by thick ridges reveal the work’s dimension. “Abstract Diptych” #41 (2016) hints more generously at its own density: on the left side of the two-canvas composition, purples, greens, whites and yellow intersperse the dominate pale brown paint ;on the right, there is a deep darker brown that appears to be impenetrable, but is in fact made up of many colors. In refusing to shout about just how complex, nuanced, and built-up they are, Hayward’s paintings behave almost defiantly, daring viewers to breeze on by when staying pays off big time.

“I would describe my dad’s paintings as visual meditations,” explains Ashely Hayward. “The mind gets lost, while the eye dances across the surface. It’s amazing to me how his works continue to reveal themselves to the viewer the longer he or she stands in place and observes. I have literally seen people transformed in amazement in front of Jimmy’s paintings. I understand that reaction. First you are struck by the beautiful, bold, heavy impasto brushstrokes, then the subtleties of the colors consume you. Finally you get lost in the rhythm of the marks, then more color variations and the play of light and shadow take hold. Truly a symphony for the eye and a delight to experience.”

Hayward’s impasto is so thick and lush the sheer weight of the sensuous, expressive abstractions on display appear to defy gravity. Why don’t those roiling impasto crests collectively ooze right off the vertical picture plane like an erupting volcano? How is it those rambunctious monochromes, highly saturated wild waves of luxuriant color, don’t spill right off the canvas onto the gallery floor like an angry ocean flaunting its power?

Magic, right? Yes, of sorts. The explanation lies in dizzying sleight of hand that can only happen when the eye stops legislating and censoring and willingly yields to the hand with a brush. The hand then takes off in a fury that results in a vibrating, eye-dazzling, meditative whole, creating the muscular mandala the artist’s daughter described.

Trying to contain the resulting all-over image is like trying to hold onto an extended jazz riff: quicksilver morphs as soon as you attempt to contain it. In full disclosure, however, what’s hard to catch feels all the more seductive. (Read, like the bad boys so many women find so irresistible.)

Confronted with a Hayward impasto, here’s a helpful hint: Don’t scan for information on the surface. It’s all in the surfaces. Surf the surfaces. You should then find it easy to lose yourself in the swirls and twirls that shape the reflected light.

“…the heart and soul of it is the marking. In my monochromes I try to avoid there ever being a special place. There’s no chosen place. It’s totally proletariat, the marking. I want the corners to be as important as the center and I want every mark to be equal in terms of importance. Ideally, the last marks just kind of blend into the earlier marks and disappear,” Hayward told a former student in an interview in Artillary magazine.

“What I enjoy while viewing James Hayward’s paintings is the rhythmic presentation of his highly saturated, intense color studies. The paintings begin to vibrate through the mark-making. The energy Hayward interjects into the brushwork is palpable. The blended multicolor works are equally intriguing because the viewer witnesses his color mixing directly on the surface,” wrote Malarie Reising Clark, director of the Telluride Gallery. “And when it comes to color, Hayward is an equal opportunity painter. His intense primary colored triptych do not outshine a grey and white diptych, both are saturated, bold, and packed with layers; both mesmerize the viewer through the in-your-face brushwork. The Telluride Gallery of Fine Art is overjoyed and honored to once again exhibit artwork of this caliber.”

“Through chromatic density, shaped by the humanity of each restless mark, Hayward’s paintings open onto a world of oneness and wonder,” wrote Frances Colpitt in a book about Hayward.

And wonder, nothing more, nothing less, is the point of Hayward’s prodigious efforts.

As if there needs to be point beyond Hayward’s testosterone-infused paintings themselves.

Dan McLeary, more:

One point of fine art is to engage us, slow us down in our thinking, in our looking, and so keep us fully engaged. Case in point, the work of artist Dan McCleary who appears to be drawing us into the silent storytelling of his frozen theatre:

“I will have the model come and pose for drawings and sometimes a photograph… The models return many times and pose in sets I build in the studio… It can take up to nine months to finishing a painting. I want to keep a prudent distance from the model. The people I paint are always people I have respect for… Once I figure out the subject, you view the painting as a complex puzzle of colors, shapes….”

Much like Cezanne, a father of abstract art, who advised artists to treat nature “by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone…”

Like with a Hayward, McCleary’s work, as we suggested, slows time down, albeit differently. His paintings present regular people engaging in everyday moments, the kind of moments he feels are life’s most precious—a passing interaction at a gas station, a wordless afternoon across from a stranger in a waiting room. By studying such seemingly incidental moments so intently, he abstracts them from their context, making their discomfort, strangeness, and beauty all the more apparent.

McCleary, who studied at the San Francisco Art Institute and has worked in Los Angeles since the 1970s, paints from models, photographs, and sets he builds in the studio. It can take up to nine months for him to finish a single painting. He alternates between working with his models for two to three-hour stretches and working on his own. Like one of his strongest predecessors and influences, Italian painter Piero della Francesca, McCleary also plays with perspective, using multi- instead of one-point perspective to make viewers feel they are in the space of the painting, not just looking at a scene. This means that paintings like “The Hostess” (2019), of an uneasy-looking woman holding menus next to a “Please Wait to be Seated” sign, are far less incidental than they at first appear.

Visit

The Hostess

In “The Rehearsal,” (2019), two men, one younger and in a sweatshirt and one older, wearing a suit, sit across from each other at a plastic folding table. A dry-erase board hangs behind them, in a room that feels uncannily vast. Both have paper cups of tea, and sit with their hands folded, staring right into one another’s eyes. If it looks like they have been sitting like this for hours, perhaps they have been. As he does in so many of his paintings, McCleary isolates this moment from any before or after. He leaves his viewers to lose themselves in particularities: the shadow cast by the highlighter on the table, the white plastic arms of the chairs.

The Rehearsal

Critic Christopher Knight tried to convey the painter’s almost religious respect for his subjects, writing “[i]n our image-saturated environment, where pictures daily flood the zone, McCleary endows small acts of everyday perception with hushed reverence.”

Pingback:Telluride: Van Beckum at Slate Gray | Telluride Inside... and Out

Posted at 22:09h, 31 August[…] Telluride Gallery of Fine Art presents the work of abstract painter/curator/teacher James Hayward and figurative painter Dan McCleary. (Go here for more on that show.) […]