30 Jun Telluride Arts’ Art Walk, 6/5: Telluride Gallery – “How the West Was Woman”

Telluride Arts’ First Thursday Art Walk is a festive celebration of the art scene in downtown Telluride, Participating venues host receptions to introduce new exhibits. Because of the July 4th holiday, the third Art Walk of the summer 2019 season takes place Friday, June 5, 5 –8 p.m.

July Art Walk highlights include a sneak-peek at all of the donated artwork to be featured at the Ah Haa School for the Arts‘ Annual Art Auction on July 19. If you can’t make it to the event, pre-bidding is welcome and there is a buy-it-now option available.

Telluride Arts’ HQ presents an exhibition of works on paper by artist Meredith Nemirov. Addressing the intersection of art and science through a series of mixed-media paintings, the work is an abstract visualization of the processes that occur beneath the forest floor. Nemirov’s work is regularly featured at MiXX Projects + Atelier. (For more on the artist, go here.)

Slate Gray presents the work of Joseph Toney. His illustrative abstractions of majestic mountains reduce his subjects to clean lines and muscular patterns. (Go here for more on the artist.)

And the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art gives credit where credit is overdue, focusing on women artists who are inspired by and paint abstractions that capture the soul of the landscapes of the American West. The show is titled “How the West Was Women.” Scroll down for a preview, including videos of the women talking about their art.

And go to Telluride Arts to read about all of the participating galleries.

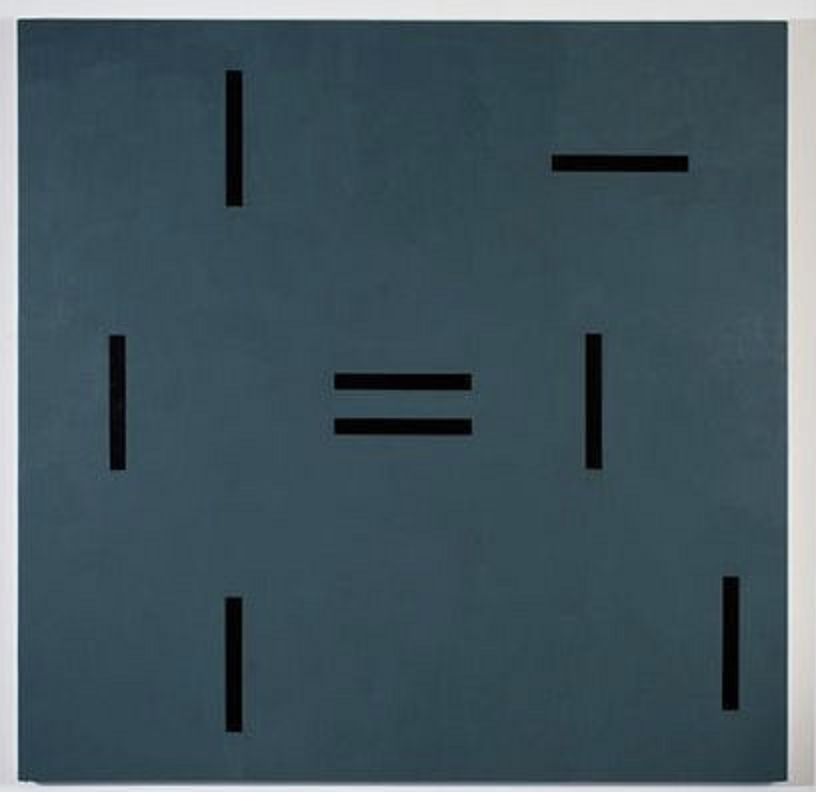

Kristin Beinner James at the Telluride Gallery, from “How the West Was Woman”

TELLURIDE GALLERY OF FINE ART: “HOW THE WEST WAS WOMAN”

Women have painted the American West for well over 100 years, their work as varied as the landscape itself and as distinctive for its power, beauty, and imagination as that of the men on the scene. But the men became brand names for their tributes to America’s wild frontier. We know the names Charles Russell, Albert Bierstadt, George Catlin, and Thomas Moran. The women? Not so much.

But the latest blockbuster show at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art helps to set the record straight. “How the West was Woman,” June 28 – July 25, 2019, showcases abstract paintings by six female artists who are inspired by Western landscape: Edith Baumann, Krista Harris, Shawna Moore, Emmi Whitehorse, Kristin Beinner James, and Victoria Huckins.

Modernism first came on the American scene with the Armory Show of 1913. And the dominance of the new modernism with its emphasis on process plus semi-abstract and nonobjective art remained largely unchallenged until the 1960s when the resurgence of interest in and nostalgia for America’s past, especially the frontier era and the settling of the West, led to an uptick in the popularity of Western realism. So now in our postmodern era, anything goes. However, collectively the work of the sextet at the Telluride Gallery maps Western terrain in keeping with distinctively modernist impulses: gesture, pattern, layer, and texture.

Born between the late 1940s and 1960s, the six painters came of age after the first generation of Abstract Expressionist women – among them, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, Lee Krasner – had completed their iconic works, but before even they had gotten their due.

Back then, the East Coast remained associated with gestural abstraction, while the West Coast had become home to hard-edge abstraction and the kind of surface-conscious, controlled minimalism perfected, albeit differently, by John McClaughlin and Lorser Feitelson. But certainly there were women painting in the West as well: Agnes Martin making her methodical abstractions in New Mexico; Helen Lundenberg marrying hard edges with soft in Los Angeles. Yet so many artists, and so much exploration, had been excluded from a canon that still too often associated abstraction with machismo, an unfortunate trend that continued from the Victorian era when other fiercely talented women were making their marks alongside the boys.

Again, “How the West Was Woman” proposes a wider, decidedly non-masculine, overdue idea of painting in and of the West. The exhibition draws (as it were) connections between a selected group of talented female practitioners who celebrate intuitive language, respond to their natural surroundings and histories, and explore the overlaps between control and loose gesture.

Edith Baumann Jazz Notes #47

Originally from Ames, Iowa, and based in Southern California for over 45 years, Edith Baumann interprets the abstracts patterns she observes in the natural world. In “Pattern Recognition No. 26” (2019), eight fuchsia rectangles streaked with black float horizontally above a dark surface. The composition reads as methodical, and yet no single element is perfectly controlled— Baumann allows the organic to interrupt her order. She describes “randomness and structure [as] two different things, happening at the same time, interconnected.”

A similar interaction between structure and intuition occurs in the work of Shawna Moore, who lives and works in Whitefish, Montana. Moore uses beeswax to make her encaustic-on-panel paintings. Sometimes, as in “Icelandic” (2018), geometric shapes define the compositions, while other paintings, like “Critical Mass” (2019), are monochromes. No matter how minimal, Moore’s process—involving layers of wax and pigment—always conveys a textured, earthy awareness of natural complexities.

James, courtesy Telluride Gallery.

Texture defines Kristin Beinner James’ monochromes. James, who works in Los Angeles, combines oil, acrylic and wax on unconventional substrates such as aluminum, meshes, jutes, or other textiles. An expanse of black pigment, in James’ hands, becomes a dense terrain that connotes sweltering asphalt and melted rubber; an expanse of pink can appear simultaneously plush and weathered, while an earthy brown merges and bleeds into neutrally-colored fabric. “The paintings,” says James, “present an other-side, a space of porous boundaries.”

The paintings of Krista Harris, who is based in Southwest Colorado, feel at once wide-open and elusive, as if they are capturing a turbulence that can never fully be understood. In “Yes, Please,” a cloud of white floats above a sea of gesture, color, and sensual marks, offering a moment of opacity in a visual universe that is almost too open and active.

Harris, Once More With Feeling

Depth and delicacy coexist in Emmi Whitehorse’s paintings, ethereal, abstract landscapes in which the presence of the wind, moving through layers of color and mark-making, is almost palpable. She works in mixed-media, painting and drawing techniques that takeb together approximate the multi-textured natural world.

Whitehorse grew up in the Navajo Nation in Gallup, New Mexico, and now works in Santa Fe, where her history and surroundings inform her art-making. Critic Lucy Lippard argues that, as “consummate abstractions” that also offer “metaphysical views from the Navajo world,” Whitehorse’s images “offer to viewers ‘from both worlds’ a glimpse of what art can be.”

Whitehorse, Mer, #16

For Victoria Huckins, who works out of an avocado grove in northern San Diego, art is discovery, each painting the result of an imaginative process in which, Huckins says, “I react to what is happening naturally within the piece.” This series of reactions results in an often exuberant, culturally savvy universe on canvas. In “Jubilation No. 6,” for example, the language of expressionism coexists with that of graffiti, and expanses of opaque color overlap lighter, agile washes. The painting conjures a sunset over the Pacific and the side of an enthusiastically, densely tagged building.

Victoria Huckins Chinese New Year

Victoria Huckins Group of 12

Aware of painting’s charged and exclusionary history, the six women artists treat the medium as a tool for bridge-making and excavation. Painting, in the context of this shown at the Telluride Gallery, is far less about avant-garde achievement and individuality than about connectivity with past, present, future, and nature. Hard edges coexist with soft ones, just as the organic and arbitrary coexist with order and pattern. Painting means many things at once, its openness here a rejection of needless and often elitist art historical divisions and categories.

In their capable hands, n#MeToo becomes #WeToo.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.