25 Dec TGFA: Berlant Nails It Again With “Tilt in Time,” Artist’s Telluride Debut Opens 12/14

The Telluride Gallery of Fine Art kicked off the winter season with “Tilt in Time,” a debut show of the work of West Coast art titan Tony Berlant. His 3D paintings and collaged sculptures have been up since December 14, 2018 and remain on display through January 14, 2019. An opening reception, attended by the artist, takes place December 28, 5 p.m.–7 p.m. Artist talks take place 5:30 p.m. & 6:30 p.m.

Additional events include Telluride Arts’ Art Walk on Thursday, January 3, 5 –8 p.m.

“Tilt in Time” features a catalogue with an in-depth, insightful essay by the prominent West Coast art critic David Pagel, who has long admired Berlant’s work.

Scroll down to watch a fun, informative video interview featuring Berlant in conversation with Telluride Gallery co-owner Ashley Hayward.

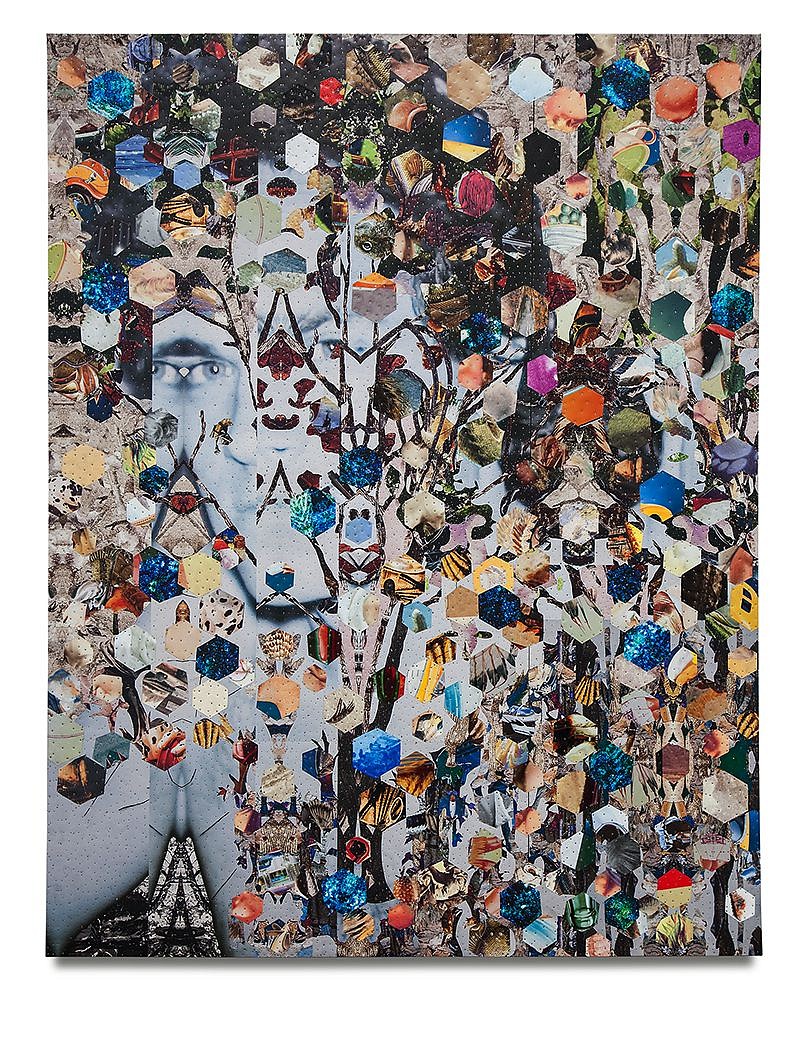

“Tilt in Time” by Tony Berlant, courtesy, Telluride Gallery of Fine Art.

“Tilt in Time” is the title of a collaged painting by Tony Berlant, which the artist fashioned using his signature collaging technique.

Unlike conventional mixed-media pieces created from cutouts of random images from magazines or photographs and taped or glued to a surface, Berlant works with photo-printed metal (using the artist’s own images, plus vintage and modern metal signage and graphics) and found tin, which he fastens to panels with shiny steel nails, surrogates for his thumb print. The end result is a hybrid that lies at the intersection of painting, sculpture and photography, also Pop art (for its appropriation and elevation of everyday objects), assemblage and abstraction. The work is, at once, all of, yet none of the above: Berlant is his own “ism.”

Further, “Tilt in Time” is a kaleidoscopic rhapsody in Titian blue that fuses the seemingly obsessive physicality which animates all of Berlant’s pieces with smartly tricked-out pictorial illusions that force the viewer into a game of hide-and-seek in a welcoming, yet somehow alien landscape:

“In these deliciously complex combinations of abstraction and representation, paths appear (and vanish), positive and negative space shift positions, fragments coalesce, patterns form (and disintegrate), and surfaces become spaces (and vice versa). Nothing stays the same. Everything changes. Including you,” writes critic David Pagel.

“Tilt in Time” is also the name of the show at the Telluride Gallery of Fine, which kicks off the winter season and debuts Berlant’s work in town, about 25 collaged sculptures and 3D paintings by this Left Coast art titan. The works are up from December 14, 2018 through January 14, 2019. An opening reception, attended by the artist, takes place December 28 5 p.m.–7 p.m.

The pieces on view in “Tilt in Time,” some brand new and Made for Telluride, technically span the last decade of the artist’s six-decades+ career – but arguably this body of work circles back millions of years to the dawn of human history and culture.

Yes really – at least according to the artist, who looks over his shoulder admiring what he has described as his “spiritual ancestors.” Time and its tilts, forward – Berlant, age 77, is experiencing a creative spurt as evidence in the Gallery show – and backward is a subtext of the show.

Tony Berlant’s “Luck of the Draw,” 2011.

“Ready to Roll, 2013.

“Here and Now,” 2010.

“Home Run,” 2018.

“Key,” 2017.

“Departure,” 2018.

“There and Back,” 2010.

Berlant, the”will to form” and finding the messages in the medium:

The “will to form” is a principle in art history that suggests the guy or girl can’t help it: artists are physically and emotionally compelled to do what they do. As long as he has worked as a professional artist, namely over six decades, Berlant has described the necessity to make art as a “basic human thing” dating back to “primitive” or “early man.”

His theory positing a creative, aesthetic intentionality that transcends mere functionality is largely based on Berlant’s personal collection and his deep dives into the theories surrounding the art of our ancestors. The works he holds dear include Paleolithic tools; talismanic “figure stones”; and Mimbres pottery, bowls dating back roughly 1,000 years when Native Americans inhabited parts of southwestern New Mexico.

Mimbres art features geometric patterns such as zigzags, spirals and checkerboards that appear to be proto-modern “depictions of various hallucinogenic plants, and the brain-generated shapes (that) manifested in the eye as a result of ingesting them,” explained the artist/collector in an interview with LA Weekly.

Berlant goes on to say: “The brain finds patterns and metaphors pleasing. This is regarding image-making strategies that encourage the viewer’s participation in meaning.”

Which Berlant’s armored quilts or sculptural paintings certainly do: some of the splintered images are quickly and easily recognizable; others not so much.

“I love crossing paths with a piece by Tony Berlant because I love looking at things that make me see there is more to reality than immediately meets the eye. Tony’s works do that more regularly and effectively than just about anything else out there. Without missing a beat, or making a big deal about their quietly mind-blowing accomplishments, his multilayered arrangements of line, shape, space and color lead me along a path of discovery that leaves me face-to-face with some of the best stuff life has to offer: what lies just beyond the horizon of what we can see on our own,” wrote art critic Dave Pagel, continuing, “So, for all sorts of reasons, I take what I think will be the scenic route and follow the path I imagine will take me past the most eye-opening vistas: curious gems for my eyes to delight in, wondrous textures for my senses to get lost in, and unexpected shifts in scale for my body to experience physically, not to mention changes in temperature, mood and atmosphere—none of which I had foreseen when I started…,” adds Pagel.

Earlier this year Berlant participated in what for academics certainly was a game-changing exhibition at the Nashar Sculpture Center in Dallas. In the LA Weekly interview, the artist explained his thoughts on the continuum of art-archeology-anthropology and, again, the “will to form” this way:

“Art was always shown to me in a cultural context; they were luxury, specially made prestige objects. But what I came to feel was that this instinct to make things, to aestheticize things, was really biological, in fact neurological, and represents a deep manifestation of self. From within their own bodies, the ‘Me’ emerged as an externalization of the psyche. It’s a human instinct, and while one could say that ‘art’ only starts with Homo sapiens, I take it back 2 million years to Homo erectus.”

“Aside from the thrill of reinventing seemingly settled matters of cultural anthropology, once again we see how lessons learned from the study of ages-old artistry speaks directly and eloquently to yet another vector of Berlant’s own art. In this case, it’s his way of deriving abstraction from the natural world and its universe of pictures, done in full awareness of how images can seem to shape-shift before our eyes,” astutely observes LA Weekly.

“One point of intersection between the ancient art that fascinates Berlant and his own work is the idea of shape-shifting. Just as neolithic stone carvers and Mimbreño potters saw shapes in the mind’s eye that are not literally there—whether due to imagination or pharmaceuticals—Berlant invites the viewer to see new things amid the endlessly complex assortments of images and texts he collages together,” adds Art & Antique.

In the world according to Berlant, the Big Idea is to “…follow your instincts and do what makes you happy.” And his aesthetic quest, as expressed in Art & Antique, is all about making “… what is invisible and strongly felt, seen.”

Tony Berlant, the backstory:

Back in the day, a young Tony Berlant lived between his SoHo studio in New York and L.A., where the locus of that avant-garde art scene was a former storefront on La Cienaga Boulevard known as the Ferus Gallery, a very special venue which nurtured the city’s first truly significant postwar artists from 1957-1966. The vanguard of the scene that emerged from that clean white cube of a space included luminaries like Ed Moses, Ed Kienholz, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Billy Al Bengston, Ken Price, Joe Goode, John Altoon, Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha – and Berlant.

But if you bracketed Berlant with those Left Coast art world titans alone you would be leaving out a large chunk of his ever-evolving story.

Adding Pop icon Any Warhol’s name to the list, an acquaintance and inspiration, inches you closer to the truth, but assemblage sculptors and collage workers Robert Rauschenberg, Kurt Schwitters and Joseph Cornell also make cameo appearances in Berlant’s narrative.

Rauschenberg, another fecund talent, taught Americans (back in the 1960s and 1970s when he loomed larger-than-life) that all of life could be open to art – from tin cans to stones to a stuffed goat, taken individually or collaged together as unlikely bedfellows.

Dadaist Schwitters actually put out a similar message first, fashioning his collages from garbage he collected on the streets and transforming society’s throw-aways into harmonious arrangements which incorporated printed material.

Using the Surrealist technique of unexpected juxtaposition, Cornell’s eccentric creations also anticipated Rauschenberg’s (and by extension Berlant’s), revolutionary thinking. His best-known creations are glass-fronted boxes into which he placed and arranged Victorian bric-a-brac, old photographs, dime-store trinkets, and other found elements. Generally referred to as “shadow boxes,” the resulting work are dream-like miniature tableaux that inspire the viewer to see each component in a new light.

Again the challenge to viewers to allow their minds to free associate and see things in a new light.

Taking nothing away from Berlant’s deep intelligence and inventiveness, which comes through in the work, the artist might also have picked up a trick or two from Frank Stella and Sigmund Polke.

Stella’s dynamic, brightly colored, highly tactile later works literally extended painting into the third dimension. Those reliefs entered the viewer’s space via protruding materials the artist incorporated in the pieces.

A multi-media artist, Polke also innovated techniques in painting and photography. And like Warhol, he both mocked and elevated consumerism and the idea of brands using the imagery of pop culture and advertising. The resulting paintings (also his photographs, film installations and prints) are at once provocative and playful.

Berlant was first drawn to printed tin signage around 1963, when a shop near his studio in Los Angeles closed down and left behind a discarded sign. Upon investigation, Berlant found not one, but several abandoned tin signs wedged behind the first one. Like a time capsule or an archeological site, each sign indexed to a different time, reduced by weathering and age to various states of rust and legibility. Those signs soon made their way into Berlant’s studio where his curiosity led him to cut them apart and play with rearranging the bits and pieces in new ways. About 10 years ago, the artist started using photographs he took himself and having them digitally spray-painted on metal, a way of expanding his lexicon and making it all much more personal.

Which art is anyway: both personal and universal (if it is good).

“I was a student and later a close friend of (Richard) Diebenkorn and other painterly painters like Ed Moses, one of my closest friends. I came out of Abstract Expressionism as a high school student. I always thought a lot like a painter, so there’s a fluidity there. And they became more and more fluid, like paintings, more atmospheric, as the years went by,” Berlant explained to the Los Angeles Times.

Berlant and Warhol:

For his Telluride show, Tony Berlant decided to include his own portrait via a set of Polaroids Andy Warhol shot of him decades ago.

The connection dates back to the 1970s, when Warhol did a photo shoot with Berlant to use for a painting that was never realized. Recently, Warhol’s estate found the full set of images and sent them to Berlant. In the piece titled “Within and Without” (2017), we see Berlant as a young man: the image is washed in a gradient of blues, and without the distinguishing eye or shock of hair edging in to the top of the work, his figure would appear somewhat abstract. The portrait is garnished with an overlaid scribble that belies the bluntness of tin snips. In the end, “Within and Without” has the same lightness of being that happens when a skilled artist touches pencil to paper – or, fast forwarding to today, finger to trackpad.

“Within and Without,” 2017.

“I met Andy because Claes Oldenburg brought him over as someone who was a collector and said ‘Oh, and also he makes things,'” Berlant explained to the LA Times. “That was before he had the Campbell Soup cans show. He was very distinctively different, very quiet. But very supportive. I don’t remember physically where (the shoot) took place, somewhere in SoHo… But I didn’t want a painting of me at the time. I told him that and he said, ‘Well, this’ll be a kind of everyman image.’ I was totally admiring of him, was delighted to have him take a bunch of photos, but I didn’t see them for a very long time, decades. Then when I saw those pictures, it was a natural thing to use one of those images. Just the fascination of being 77 and seeing an image of yourself from so long ago, and also made by Andy, it’s a kind of collaboration after the fact. It’s also using the Andy portrait as an artifact — if you’re gonna appropriate anything, what’s more appropriate than appropriating an Andy Warhol photograph of yourself — it’s sort of a strange circle. And I think it’s the only photograph I ever had made of me with my shirt off,” the artist explained, adding: “Andy was fascinated by L.A. and Tab Hunter and Dennis Hopper and actual movie stars. He would say, ‘Is your name really Tony Berlant? Billy Al Bengston, Joe Goode? These are your real names?’ He just thought it was all so fantastic.

“I used that Warhol photograph of me as a touchstone…an homage, a remembrance of Warhol,” Berlant told the Gallery.

“One of One,” 2018, featuring polaroid imagery by Andy Warhol.

Coincidently, Warhol, who began his life in the fast track as a commercial illustrator, first exhibited in an art gallery in 1962 when – wait for it – the Ferus Gallery, the very same venue that helped launched Berlant’s career, showed his 32 “Campbell Soup Cans, 1961-1962.”

Trends in the art world come and go like mountain weather. However, Warhol remains a Top Dog to this day.

And so does Tony Berlant, a force in the West Coast Pop Art movement of the 1960s – and still nailing it today (literally).

Right now Warhol is enjoying a major retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum. At the exact same time Berlant is featured in our box canyon at the Telluride Gallery, where co-owner Ashely Hayward, the show’s co-curator (along with her staff), is all about showcasing the work of the greatest West Coast artists, an elite fraternity that includes her dad, James Hayward (who also consults from time to time on Gallery shows).

“Growing up with my father meant growing up with founding members of the Cool School, including Tony Berlant,” Hayward explains.

“…(Berlant’s) deeply personal output remains relevant to a modern era of iPhones and Instagram feeds—(his) cacophony of images, rolling on like waves on the shore,” concludes the Gallery in what could be a tweet – but no thanks.

An interview with Tony Berlant:

More about Tony Berlant:

Tony Berlant, courtesy the LA Times.

Tony Berlant was born in New York in 1941 and moved to Los Angeles shortly thereafter, where he received his BA, MA, and MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles. He also taught at his alma mater for four years in the ‘60s. Berlant has exhibited internationally and was included in notable exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City; the Museo Rufino Tamayo, Mexico City; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris. His work is included in the public collections of a number of institutions including the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City.

Berlant’s interest in collecting and studying anthropological artifacts has led to two books and subsequent curated exhibitions. “First Sculpture: Handaxe to Figure Stone,” was co-authored with the anthropologist Thomas Wynn and culminated in a curated exhibition which debuted at The Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. His research into Mimbres pottery prompted the recent exhibition, “Decoding Mimbres Painting: Ancient Ceramics of the American Southwest” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. A book by the same title in collaboration with Evan Maurer and Julia Burtenshaw was also produced. Berlant was also pivotal in founding the Mimbres Foundation, a group dedicated to the research and preservation of Mimbres pottery.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.