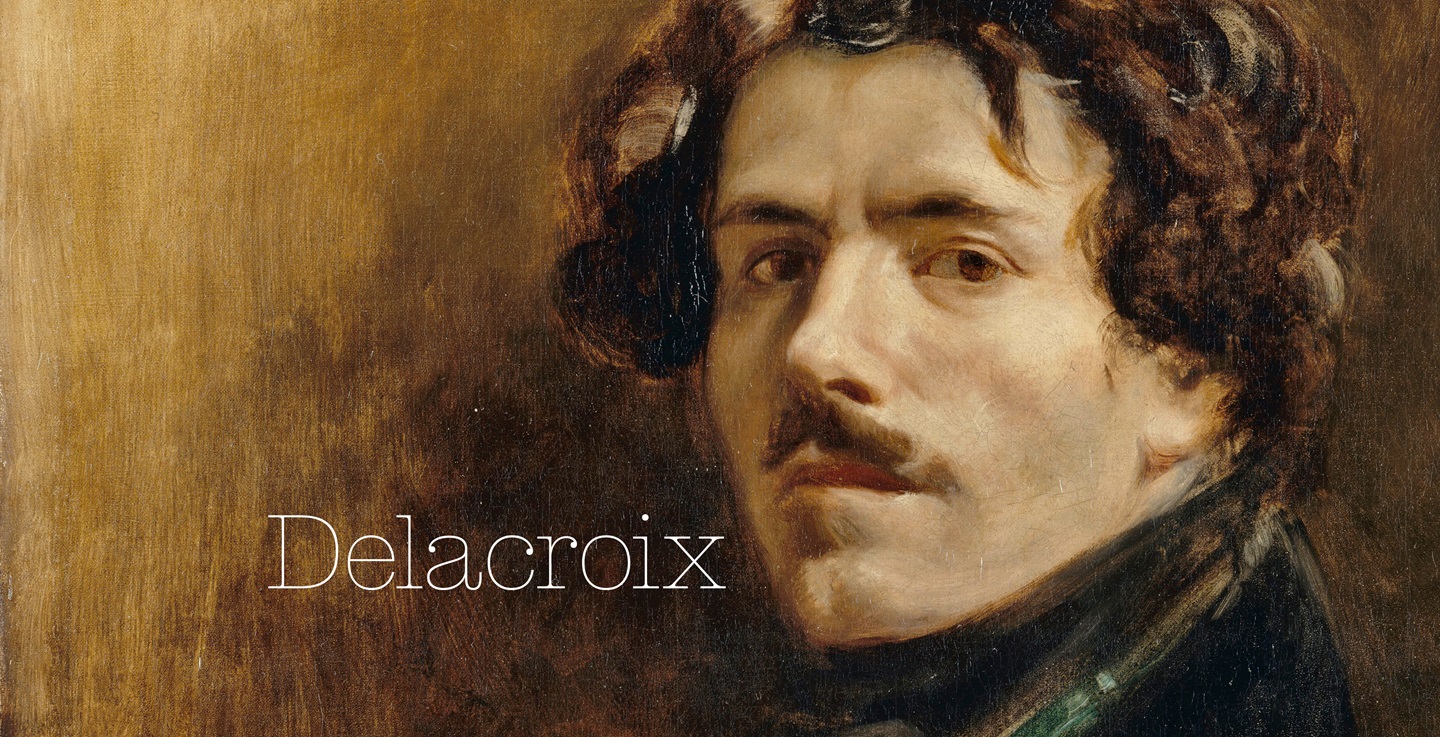

08 Oct TIO NYC: Delacroix at The Met: Marc & Macke at the Neue

The”Delacroix” show at The Met runs through January 6, 2019. Franz Marc and August Macke at the Neue Gallerie is up through January 21, 2019.

The epic exhibition of the work of the Romantic painter Eugene Delacroix, (1798–1863), more than 150 paintings, drawings, prints, and manuscripts— is mounted in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Tisch Gallery – which is right next door to the galleries on the second floor that house Impressionist art.

That may not be an accident. Or if it is, it is a happy one.

Rebels from Paul Cézanne to Vincent van Gogh, from Gustave Courbet to Henri Matisse bow to Delacroix. Cezanne’s “The Apotheosis of Delacroix” (1890-04) shows him with his fellow artists worshipping as Delacroix is transported aloft. Henri Fantin-Latour’s “Immortality” imagines an angel scattering roses on Delacroix’s name, inscribed across a Paris park.

The Apotheisos of Delacroix, Paul Cezanne

Wacky hyperbole? For sure. But Cezanne is quoted in the introduction to the sprawling show as saying “You can find all of us … in Delacroix.”

As Van Gogh wrote in 1885: “What I find so fine about Delacroix is precisely that he reveals the liveliness of things, and the expression and the movement, that he is utterly beyond the paint.”

Which was one of the artist’s key objectives, bringing the inner life, the vitality of subjects – people, animals, landscapes, even florals – to the surface.

Case in point is Delacroix’s “Lion Hunt” – or at least a fragment, the lower half, because the top half was destroyed in a fire in 1870. The painting is a cacophonous tangle of man and beast summarized in vibrant, or better, violent, reds and oranges. The swirling, expressive brushstrokes and bold colors of the fighting men and their flowing, luminous garments is echoed in the waves of the water and the clouds moving across the sky.

Sketch for The Lion Hunt.

In that work, the apotheosis of the show, Delacroix was without a doubt inspired by the lion hunt paintings of Peter Paul Rubens, but the blurs and slashes of the paint are as spontaneous, physical and tactile as the work of any one of the great Abstract Expressionists. Squint hard and you might see, as we did, the foreshadowings of Jackson Pollack or certainly the kinetic energy inherent in any Pollack .

The inherent violence and the way Picasso blocked those images to unfold the tragic drama in the composition also points to ”Guernica.”

And, as it turns out, Picasso is yet another art world titan who bows to Delacroix’s talent. As Picasso reputedly told the painter (and his lover) Françoise Gilot: “That bastard. He’s really good.”

Making a grand entrance onto the world stage as he did just after the fall of Napoleon, Delacroix became an engine of a revolution that helped transform French painting in the 19th century and beyond, a good thing because his noble, monied family lost it all in the other, much bloodier revolution and the artist seems to have needed to reclaim their place in the sun.

What Delacroix did was to reimagine ways to capture the unique interplay between light and form. He was also intrigued with optical effects, a legacy of daVinci, the bold use of color. His passion for the exotic was triggered during and after his trip to Morocco and continued throughout his long, prolific career. His example inspired the spontaneity of the Impressionists, the dreamy allusion of the Symbolists, and the saturated color palette made famous almost a century later by such artists as Renoir, Monet and Matisse – all in the name of Romanticism.

At the end of the 18th century and well into the 19th, the movement known as “Romanticism” spread throughout Europe and the United States, challenging the rational ideal so tightly held during the Enlightenment. Artists of all stripes came to emphasize the idea that sense and emotions – not simply reason and order – were equally important means of understanding and experiencing the world. Romanticism celebrated the individual imagination and intuition in the enduring search for individual rights and liberty.

“A picture is nothing but a bridge between the soul of the artist and that of the spectator,” Delacroix said, adding, “The source of genius is imagination alone, the refinement of the senses that sees what others do not see, or sees them differently.”

Defining art, Delacroix concluded: “Cold exactitude is not art; ingenious artifice, when it pleases or when it expresses, is art itself. “

According to The Met:

“…Delacroix produced an extraordinarily vibrant body of work, setting into motion a cascade of innovations that changed the course of art. This exhibition is the first comprehensive retrospective devoted to this amazing artist ever held in North America.

The exhibition, a joint project with the Musée du Louvre, illuminates Delacroix’s restless imagination through more than 150 paintings, drawings, prints, and manuscripts—many never before seen in the United States. It unfolds chronologically, encompassing the rich variety of themes that preoccupied the artist during his more than four decades of activity, including literature, history, religion, animals, and nature. Through rarely seen graphic art displayed alongside such iconic paintings as Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826), The Battle of Nancy (1831), Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834), and Medea about to Kill Her Children (1838), this exhibition explores an artist whose protean genius set the bar for virtually all other French painters.”

Among our favorites in the show: Delacroix’s naughty but nice “troubadour” paintings, sexy nudes that suggest the artist’s unique command of flesh tones – and of his models. (Yes, not #MeToo.)

Also his “Studies of Tigers and Men in 16th-Century Costumes,” bravura poetry executed in brown ink and watercolors.

Then, close to the end of the show, are three very uncharacteristic landscapes, devoid of people or action. A modernist pause that refreshes before the mayhem of the aforementioned “The Lion Hunt.”

“A glorious retrospective . . .” —New York Times(Critic’s Pick)

“There’s no lack of celebrated and ravishing paintings.” —Wall Street Journal

“C’est magnifique!” —Daily News

“. . . a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience the painter anew.” —Art & Antiques

Roberta Smith of The New York Times described Delacroix as “A precocious prophet of the modern age.” Her review, which includes great detail about his life and work, follows.

The achievement of the French painter Eugène Delacroix — the Romantic paragon of 19th-century French art — is like a huge puzzle whose pieces don’t easily fit together. But at least we finally have a chance to try to make them cohere.

The first full-dress retrospective in North America devoted to this complex, enigmatic, foundational figure, titled simply “Delacroix,” opens on Monday at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Organized with the Louvre Museum in Paris, where it appeared in fuller form this year, the Met show presents nearly 150 paintings, prints and drawings in a dozen large galleries whose arrangements sometimes have the clarity of individual exhibitions. Some of his biggest, most famous paintings are staying home, but enough prized Delacroixs from the Louvre, other French museums and elsewhere — including the hypnotic “Women of Algiers in Their Apartment” and the grim “Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi” — are on hand to account for an astounding career.

As Picasso told the painter Françoise Gilot: “That bastard. He’s really good.”

And yet this precocious prophet of the modern age does not conform to our ideas of unalloyed progress. While he opened the door to Modern painting as a process, he kept it tightly closed to modern life.

The show has been assembled by Asher Miller, associate curator of the Met’s department of European paintings, with Sébastien Allard, the director of the Louvre’s department of paintings, and Côme Fabre, its curator. Their selections give us, in largely chronological order, Delacroix the talented student; the portraitist of his loved ones and of big cats; the illustrator; the misogynist bachelor and Orientalist; the frequent star of the Paris Salon; and the painter of religious commissions and of slightly naughty (but highly salable) troubadour paintings.

Delacroix also rendered possibly the most convincing newborn in Western painting (in “The Natchez,” with its idealized Native American parents). He seems to have been an incessant draftsman, doodling in the margins of print proofs, always with much on his mind. In one of the show’s most stupendous drawings, “Studies of Tigers and Men in 16th-Century Costumes,” Delacroix repeatedly draws, in brown ink and watercolor, both the animal at rest and its regal head. But in the upper corner, several Dutch burghers are lightly sketched in graphite, as if thoughts of Rembrandt and Hals had suddenly intruded.

There are also nearly 120 more drawings to be seen in the exhibition “Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugene Delacroix,” in nearby galleries. The Cohen works suggest that Delacroix’s horses on paper are superior to his overly stylized steeds on canvas. This collection also includes a wonderful study for the immense “Christ in the Garden of Olives (The Agony in the Garden)” of 1824-26, a gorgeous, packed, newly cleaned vision of Christ, in a splendid orange wrap, pushing away the angels as soldiers draw close to arrest him.

This work was Delacroix’s first religious commission, introduced in the Salon of 1827, and it opens the retrospective, hanging beside its Salon alum “Mortally Wounded Brigand Quenches His Thirst.” A small, superbly unified work, it shows its handsome protagonist crouched over a stream, drinking water stained with his own blood. It portends Delacroix’s unusual control of skin tones to add drama; death is on the man’s face, but his hands are slightly more robust.

By this time, Delacroix had already asserted his rejection of the neo-Classical credo of firm outlines, polished paint handling and perspectival logic. His embrace of color, freewheeling brushwork, frequent distortions of space and intensifications of motion had established him as a leader of French Romantic painting when he made his debut at 24 in the Salon of 1822. His ideas about the physicality of painting, mostly gleaned from studying the work of Rubens, Veronese and others at the Louvre, opened the medium to the modern era.

“You can find all of us … in Delacroix,” Cézanne said. Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Expressionism gestate in his art. Stare at “Apollo Slays the Python, sketch,” a study for the ceiling of the Louvre’s Gallery of Apollo, commissioned in 1850, and a van Gogh sunflower may stare back. The oil sketches here outshine finished versions that hang nearby, especially the more emotionally compelling study “Medea About to Kill Her Children, sketch.” Some sketches are startlingly prescient. The robust red and orange blurs of “The Lion Hunt,” based on Rubens, in the show’s final gallery, are as improvisatory as a de Kooning.

The enigma of Delacroix has several aspects. First, how was he able to do so many different things, so early, and for so long? Born into privilege in 1798, Delacroix expected great things of himself and was almost desperate for fame. Becoming an impoverished orphan at 16 seems to have spurred his ambition and industriousness, while also creating a need for income (although the great diplomat Talleyrand, sometimes rumored to be Delacroix’s real father, was a frequent protector). Even in his 20s, opportunities to illustrate books and undertake public commissions began to pile up…

Neue Gallery:” Franz Marc and August Macke: 1909 – 1914″

German Expressionism is the name given to an artistic movement that was a reaction to the conservative social values that continued at the turn of the 20th Century.

Expressionist artists rejected the stale, stolid traditions of the state-sponsored art academies, instead turning to boldly simplified or distorted forms and exaggerated, sometimes clashing colors. Directness, frankness, and a desire to startle the viewer out of bourgeoise stupors characterize its various incarnations. Many of the German Expressionist artists had served in the military during World War I. Two of the best known, August Macke and Franz Marc, were killed.

“Franz Marc and August Macke: 1909-1914” explores the life and work of those two artists and the power of their friendship.

In the four years prior to Macke’s death in 1914 – Marc died in 1916 – they wrote each other scores of letters, visited each other’s homes, traveled together, often discussing the development of their work. They shared ideas about art and, through their innovations, helped put German Expressionism on the world stage.

Featuring approximately 70 paintings and works on paper, “Franz Marc and August Macke” is comprised of loans from public and private collections worldwide. While Marc has received acclaim in the United States, Macke did not become well known. This presentation at Neue Galerie New York is the first time Macke’s work is being shown in an American museum exhibition. The show is also the first in the United States to explore the relationship between the two men.

These artists forged a friendship in 1910 based on their shared interest in French art and, more specifically, in the work of Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Fauvists, whom they discovered during their time in Paris. Both men expressed the same spiritual fascination for landscapes and nature in their initial paintings, often painting like the Impressionists en plein air.

Their paintings took a more radical, stylized turn when they met Vassily Kandinsky in 1911 and founded the Der Blaue Reiter Almanach or The Blue Rider Almanac.

Marc abandoned plein air painting in favor of his famous blue horses – which inspired the title of the almanac. While Marc co-edited the Almanach with Kandinsky, August Macke compiled the ethnographic visuals and wrote a study on African masks, traces of which show up in the Neue show.

Highly active in their field, the two men helped organize international avant-garde exhibitions: Cologne in 1912; Berlin in 1913, at the same time continuing to develop their art.

As part of this evolution, Marc turned to abstract art in 1913 under the influence of the Italian Futurists and Robert Delaunay’s Op paintings. Macke then moved away from Kandinsky’s intellectual spirituality and towards a clearer relationship between humans and nature, particularly during his travels to Tunisia with Paul Klee.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.