12 Oct TIO NYC: Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich at Jewish Museum

“Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922” at The Jewish Museum is up through January 6, 2019.

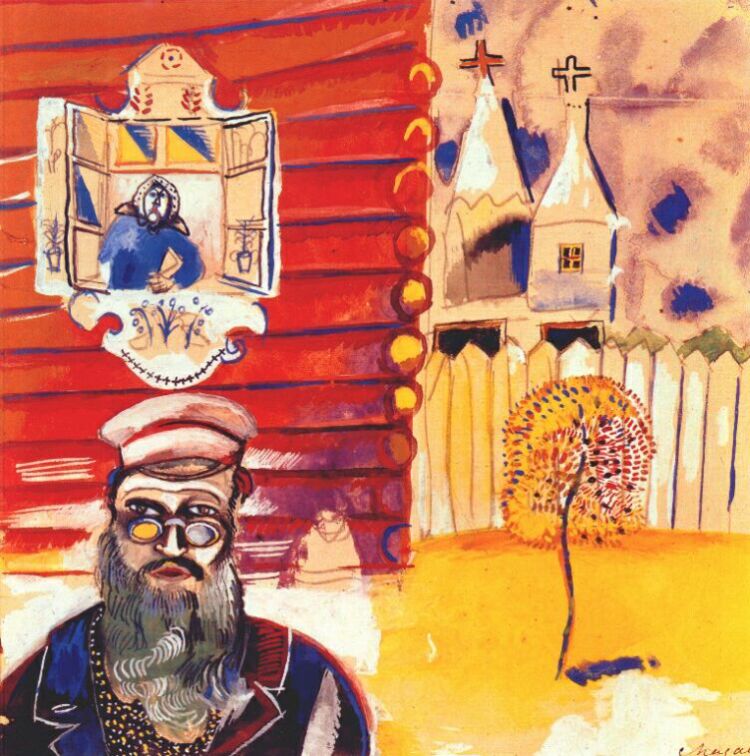

Chagall’s Old Man with Glasses, a gem.

Once upon a time just after the Russian Revolution that toppled the Czar and his family, three artists vied for the creative souls of their students at a little known, nearly forgotten school in a long forgotten place in Russia.

The story of Marc Chagall v. El Lissitsky and Kazimir Malevich, 1918- 18922, is based on real events that occurred at the time of Chagall’s short-lived return to Vitebsk, his home town, in 1917-18. In this time he created the Academy of Modern Art or the People’s Art School, a bulwark in a time of ideological ferment, inspired by the artist’s dreams of a bright and beautiful future for plain vanilla workers longing to express themselves beyond the humdrum of hard labor.

Chagall’s fantasy was crushed – for a short time – by the other two artists’ dogma, an artistic style with spiritual aspirations known as Suprematism, which Malevich invented. It was one of the earliest and certainly the most radical developments in abstract art to date. The name is derived from Malevich’s belief that Suprematist art would be superior to all the art of the past and would lead to the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.”

Bottom line: Suprematism was a (futile) search for art’s barest essentials, a “zero degree” of painting – whatever that means. The “ism” encouraged the use of stripped down motifs, since they best articulated the shape and flat surface of the canvases on which they were painted. (Ultimately, the square, circle, and cross became the group’s favorite motifs.)

In the end, however, the Soviets trounced Suprematism and Chagall lived on to mock his rivals in sarcastic stage designs and thrive. Big time.

“Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922” puts that drama in high relief.

And some of the Chagalls on display leave no doubt why he and his helium-filled fantasies in which goats and cows and an eternally wandering Jewish man sail through the night sky and fiddlers fiddle on roofs got the last laugh. No really: The painter known to the world as Marc Chagall was born Movsha (Moses) Shagal on 7 July 1887, into a poor family living on the fringes of the Russian empire. When he died 98 years later, he was the last surviving member of the School of Paris and a multimillionaire with a flat on the Isle St Louis in Paris and a villa in the south of France – minus the fiddlers dancing on either roof.

Three cheers for exotic subjects rendered fancifully in highly saturated colors. The sheer energy of Chagall’s whimsy continues to enchant.

The New York Times described the show as “crisp and enlightening.”

The Museum summarizes the show this way:

The year 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of Chagall’s appointment as Fine Arts Commissioner for the Vitebsk region, a position that enabled him to carry out his idea of creating a revolutionary art school in his city, open to everyone, free of charge and with no age restrictions.

The People’s Art School was the perfect embodiment of Bolshevik values, and was approved in August 1918. A month later, Chagall was appointed Fine Arts Commissioner. El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich, leading exponents of the Russian avant-garde, were two of the artists invited to teach at the school. A period of feverish artistic activity followed, turning the school into a revolutionary laboratory. Each of these three major figures sought, in his own distinctive fashion, to develop a “Leftist Art” in tune with the revolutionary emphasis on collectivism, education, and innovation. The exhibition traces the fascinating post-revolutionary years when the history of art was shaped in Vitebsk, far from Russia’s main cities.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 had an enormous effect on Chagall. The passage of a law abolishing all discrimination on the basis of religion or nationality gave him, as a Jewish artist, full Russian citizenship for the first time. This inspired a series of monumental masterpieces, such as Double Portrait with Wine Glass (1917), celebrating the happiness of the newly married Chagall and his wife Bella. As the months went by, Chagall felt the need to help young residents of Vitebsk lacking an artistic education, and to support other Jews from humble backgrounds. Once he was named commissioner for the arts in his city, his first task was to organize festivities marking the first anniversary of the October Revolution. The streets of Vitebsk were transformed into a sea of colorful banners and signs designed by Chagall and the young David Yakerson. Studies for these banners will be on view in the exhibition. After the celebrations, Chagall devoted himself to creating his school which was officially inaugurated on January 28, 1919 with the goal of providing a high level of teaching in all art styles.

While the first teachers left before the spring, they were replaced by others. El Lissitzky took charge of the printing, graphic design, and architecture workshops. The leader of the abstract movement, Kazimir Malevich, founder of Suprematism, was a charismatic theorist who galvanized the young students upon his arrival in November 1919. He formed a group with sympathetic teachers and students called Unovis (champions of new art). Suprematist abstraction became the new paradigm. Lissitzky, as a trained architect, played a crucial role in the newly founded collective. With his extraordinary Proun series (projects for asserting the new in art), he was the first to extend architectural volume to the pictorial plane, considering the series as “stations where one changes from painting to architecture.”

Chagall continued to produce his individualist art while making ironic use of the language of non-objective art promoted by Malevich and his students. Meanwhile, during his time in Vitebsk, Malevich began to abandon painting – an exception being his magisterial painting Suprematism of the Spirit (1919), included in the exhibition – in favor of his main theoretical writings and education. A methodical and stimulating teacher, he attracted more and more students, while attendance to Chagall’s classes gradually dwindled.

Chagall’s dream was to develop a revolutionary art independent of style or dogma but this came to an end in the spring of 1920. He decided to leave Vitebsk in June and went to live and work for the Jewish theater in Moscow. After Chagall’s departure, Malevich and the Unovis collective, now in command, worked at “building a new world.” Collective exhibitions were staged in Vitebsk and major Russian cities. With the end of civil war in 1921-1922, the political climate changed again. The Soviet authorities decided to impose ideological and social order, eliminating artistic movements which did not directly serve the interests of the Bolshevik party. In May 1922 the first graduating class of the Vitebsk school of art was also the last. During the summer, Malevich left for Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) with several of his students, and continued to develop his ideas on volumetric Suprematism, building models of utopian architecture called Architectones, and designing porcelain tableware. A number of these works are shown in the exhibition. Moving to Berlin in 1922, Lissitzky further developed his Prouns and, later, had his first solo exhibition in Hanover.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.