26 Aug Telluride Film Fest at Telluride Gallery: Moses, Liepke, Stills from Major Feature

Ed Moses is the “Master of Crazy Wisdom.” A show featuring examples of his late work at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art continues through the 45th annual Telluride Film Fest. Please scroll down to learn more about the life and work of the artist, a close family friend of Ashley Hayward, gallery co-owner, who curated the exhibit and produced the video (below).

Keeping company on the walls with Moses’ abstractions is new work by the “Master of Sensuality,” Malcolm Liepke, whose show opens with Film Fest and continues through September 12. Liepke will be on hand at the gallery during Telluride Arts’ September Art Walk , Thursday, September 6. Scroll down for more on the artist. And stay tuned for a much more in depth profile next week for Art Walk.

Special to the Telluride Gallery for the Telluride Film Festival are stills from one of the major features being screened over Labor Day weekend. You will have to stop by to find out which director and which film is in the spotlight.

Crazy wisdom.

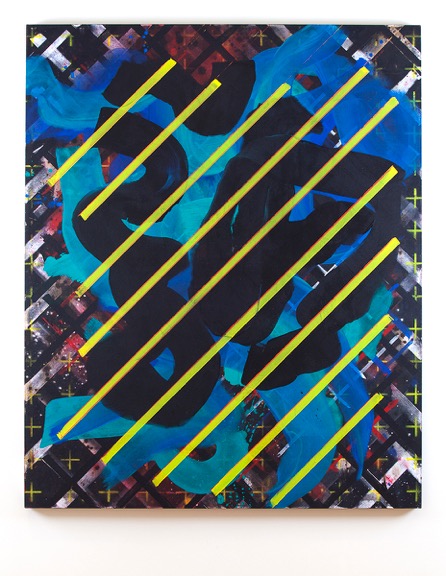

The notion sums up eye-popping paintings on the walls today at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art, tying the package together with a nice, neat bow.

Crazy wisdom also inspired the title of the current exhibition at the gallery, which showcases outstanding examples of some of the late work of art world titan Ed Moses, widely celebrated for his ever-changing, provocative style of painting. Moses’ career spanned no less than seven decades. According to the show’s curator, gallery co-owner Ashley Hayward, a close friend of the artist, the man was still going at it (from his wheelchair) two weeks before his death in January 2018.

There is a painting that hangs over the fireplace in Ashley Hayward and Michael Goldberg’s living room that says it all.

In New York, hard-edged geometry and abstract expressionist process painting defined two very separate worlds, two distinct schools, the former always at one cool remove; the latter, very physical, the artist’s thumbprint everywhere to be seen. In this particular Ed Moses work, a black AbEx background is anchored, (held in place from unraveling?), by a black rectangle and a green rectangle, which also defines the picture plane, marking the divide between our world and the world of the painting. Here the two disciplines conduct a dialog. Was Moses commenting on “isms.” Was he trying to say in this one of his later works, that it is all art, so who cares?

Universally considered one of the foremost post WWII abstract artists, Moses was dubbed by his spiritual teacher, “Master of Crazy Wisdom,” hence the title of the moving tribute to the artist, 22 paintings in all, painted between 2015 and 2017, now on display at 130 East Colorado Avenue.

“Master of Crazy Wisdom” officially opened July 19 and runs through Film Fest.

The artistic odysseys of Ed Moses are the stuff of legend, his flights of fancy combining as they did self-exploration, daring, irreverence, and supreme self-confidence tempered with humbleness.

Look at any of Moses’ images on the gallery walls, it is as if his brushstrokes are sensate, as if there was an active dialogue between the painter and his medium, with the medium shouting ideas of its own and the artist listening. Which makes sense for a man to whom the process of painting came as naturally as breathing. According to art critic and lifelong friend, Frances Colpitt, it was as if “…the brush were an extension of his arm and body, and the paint a bodily fluid, this bionic relationship to his tools and materials is plainly evident in the finished and ever fresh paintings.”

As an artist, Moses underlined the point about the visceral, instinctual nature of his work by talking about his modus operandi in terms of giving up all attempts at controlling confusion and instead learning to be in tune with it, to swing with it.

Ashley Hayward first met Ed Moses – or he her – when she was a babe in diapers, a simple fact which opens the door to the history of the LA’s modern art scene in which Ashley’s father, James Hayward, has loomed as a large presence for most of his 70+ years. (Hayward once told us he started painting at age four.)

That story also explains the subtext that underlies every one of the major shows at the Telluride Gallery since Ashley and her husband Michael Goldberg took over the venue from its original owners in January 2017: each of them has honored at least some of the major LA artists in the Haywards’ orbit – including James Hayward himself.

Here goes…

In the mid-1940s, when the center of the art scene shifted from Paris to New York, Los Angeles was something of a cultural backwater. That all changed, however, when the very prolific Ed Moses helped form a collective that become known as the “Cool School,” which transformed LA and the Left Coast in general into a major player on the world stage of modern art.

In the 1960s, the locus of that avant-garde was a former storefront on La Cienaga Boulevard, the Ferus Gallery, which nurtured the city’s first truly significant postwar artists from 1957-1966. The vanguard of the scene that emerged from that clean white cube of a space included luminaries like Ed Kienholz, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Billy Al Bengston, Ken Price, Joe Goode, John Altoon, Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha – and, at the top of the heap, Moses. They were all good-looking men, hard-living, hard-drinking surfers, beatniks and lovers of women, whose work was a stylistic combo of Pop, hard-edged or geometric abstraction and minimalism.

Kienholz, for example, created “assemblage art,” using bits of garbage and used cars; Ruscha created paintings of words and signs. Others drew from the car and surf culture, fiberglassing and airbrushing to create their pieces.

And Moses? He became a Master of Crazy Wisdom, adapting the spontaneity, jazz-like improvisation and freewheeling, muscular gestures that characterized the loose confederacy of artists known as Abstract Expressionists, introducing a West Coast sensibility to the idiom.

“Growing up with my father meant growing up with founding members of the Cool School like Ed and other greats like John Baldassari, Tony Berlant, Gywnn Murrill, Dan McCleary and Chris Burden, one of Ed’s students, whose stunning “Urban Light’ is now a landmark that stands outside the LA County Museum.”

Growing up, what Ashley saw was a group of artists who seemed to feel they had no orthodoxy to rally against, no critical establishment to buck, so they all pushed the envelope with impunity – unlike the Right Coast artists in New York, who rarely ventured outside their little fiefdoms with representational artists mixing with other representational artists; Color Field painters socializing with other Color Field painters; minimalists with other minimalists.

“My father’s circle, California artists of all stripes, respected one another. Our family friend, critic David Pagel, described the LA scene as completely unique, where artists from all walks of life came together to support one another’s work. There were no boundaries.”

Ashley’s earliest memories of Ed Moses date back to when she was four or five. The relationship that evolved remained close; her admiration for the man and for his work at the center of her thoughts and their conversations:

“Ed would deflect any of my attempts at flattery,” said Ashley. “But over the years we did talk a lot about spirituality. About the importance of being in the present moment.” continuing: “In these his last works, hesitation is abandoned and replaced with a deep well of inspiration and purity of process. His final works are embedded with a lifetime of experience, passion and masterful application.”In that context, “process” rhymes with “action painting” and “Abstract Expressionism.”

As a spiritual descendent of the AbEx movement, Moses was all about the notion of the canvas as an existential “arena in which to act” “rather than the ground of an aesthetic pursuit” (per art critic Harold Rosenberg).

Put another way, according to Hayward, Richard Diebenkorn, an artist who, like Moses, was a dean of California artists (and whose career was jumpstarted by Moses) once summarized the way he operated in his studio as the need to “assault” the canvas. While interviewing Moses for the charming and informative video that accompanies the gallery show, Hayward reports she hesitated, but decided to pass the idea of Moses’ colleague on to her subject. His reply surprised her:

“’Yes, yes,'” he told me, “‘you have to jump on it, go for it. You have to be aggressive and hit it hard. You can’t be tentative. You have to be direct.’”

And you have to be seen.

You have to leave your mark. In a recent interview just before his death, Moses talked about being terrified that he was going to disappear into “some invisible zone.”

His hedge was to leave ever-evolving marks on canvas like the cavemen who left handprints on cave walls, each painting standing as a totem to Moses’ illuminating “non-journey.”

James Hayward suggested his friend’s attraction to Buddhism had to with the dharma of non-judgment and and non-attachment, which means boils down to the ability to walk freely between attraction and aversion, likes and dislikes, praise or blame, without attaching to one side or another, and without being jerked this way or that.

Without being attached to any particular outcome.

To that point, Ed Moses’ son Andy, a prominent artist in his own right, was quoted in several obituaries as saying of his dad: “He never ceased to push the envelope and he stayed so engaged in painting every step of the way. He was a true explorer and he was just able to pull it off every time. Most artists sort of struggle through transitional periods and he didn’t have any transitional periods. He would abruptly stop one body of work, start another and have it fully realized.”

True even to the 11th hour before his death.

“My painting is the encounter between the mind’s necessity for control and it’s yearning to fly…,” explained the artist.

Whether Ed Moses believed in reincarnation or not, he lives on through his art which, in all its incarnations, his drawings, paintings, prints, vellum installations, stencils and spray painted works, will never lose its distinctive intensity.

More about Ed Moses and Crazy Wisdom:

Ed Moses, courtesy LA Weekly.

Crazy Wisdom was a term coined by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a major figure in bringing Buddhism to the West – and Ed Moses’ spiritual teacher.

The story goes that during his life, Moses became increasingly interested in Eastern philosophies and attended meditation retreats. On one such retreat with the Shambhala sect of Buddhism, when asked to sit still and upright for hours at a time, participants were hit with a stick if their postures began to slouch. After being reprimanded several times by a woman with a stick, Moses finally screamed out amidst a room of silent meditators: “You touch me with that fucking stick one more time, I’m going to break all your fingers!”

Shortly after, Moses was asked to come speak Chögyam Trungpa reportedly told Moses: “In this sect of Buddhism there is this thing called crazy wisdom. I think Ed, you are the master of crazy wisdom.”

Chogyam Trungpa defined crazy wisdom as an innocent state of awareness that is wild and free, completely awake and fresh. It is a spiritual worldview that represents thinking outside the box—moving against the stream.

Moses – and for that matter, his Cool School cronies and James Hayward – to a “T.”

Ed Moses officially became a Buddhist in the 1970s, drawn to that path by the idea that we are not solid; we are all works in process. Hence his paintings all are works-in-process too, which over the years have ranged from his early “Rose Drawings” the result of tracing rose patterns he found on an oilcloth from Tijuana to process-based work using different, often unconventional materials – squeegees, mops, sponges, squirt bottles, hoses and chalk snap lines – to create stunning new work.

“Ed always came across to me as a pure, uninhibited soul, who projects all that onto his canvasses,” continued Hayward during our Cubist-shaped talk. “When I asked him what he was thinking about when he was painting, Ed’s reply was characteristically evasive: ‘Whatever is there is what’s happening. Asked when a painting was done, he told me, ‘When it has a life of its own, I step back.’”

The ongoing dialogue of gesture and grid, which Moses repeated over the course of his career, is, according to Colpitt,” beautifully summarized in Telluride Gallery’s exhibition of his late works,” adding this coda:

“Throughout the seven decades of his career, Moses’s high-decibel color sense continued to develop. Rarely tonal or modulated— except to the extent that a swipe of the squeegee or brush pulls rainbows of contrasting hues across the surface—his colors are brash and jarring: pink and orange, turquoise and lime green, or lemon yellow and magenta. His colors grew more saturated and intense, his application of them more impulsive and urgent, evoking ever deeper emotional resonance. As his life progressed, Moses felt a strong kinship with shamans and prehistoric cave painters. The raw vigor of his process combined with the dark mysteries of the painted caves came to fruition in this last body of work.”

“This dual mode in his art making was second nature for Moses in much the same way that the yang of his studio work and the yin of his philosophical pursuits were inseparable. Art critic David Pagel described him as “unrestricted id flowing out there in the world.” The artist continued to fearlessly charge the fray, endlessly experimenting, discovering. His generosity, determination, focus, and tireless dedication to innovation will surely continue to stand as a timeless marker for countless generations of artists to come. As a master of crazy wisdom, Ed’s work and practice emulates the wise embracing of our own dualities and nuanced selves: saints, masters, poets, mad scientists and fools,” summed up the gallery.

Malcolm Liepke in brief:

Largely self-taught, Malcolm T. Liepke paints in a style that reflects the work of other sensuous painters of women – John Singer Sargent, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Diego Velázquez, and James McNeill Whistler, among others – to create portraits that are at once visually familiar, yet wholly his own.

Liepke favors studies of ordinary women whom he places in glamorous contexts, namely center stage of his oils. The voyeuristic nudes, which the artist creates with loose brushstrokes and dusty gray-green skin tones are, yes, sexualized, but they are powerful too. Liepke’s subjects look the viewer straight in the eye – or look away in utter indifference. And they own their sensuality, which they convey through simple gestures and pointed expressions.

Liepke paints from photographs and works in a wet-on-wet technique borrowed from artists like Sargent and Velázquez, in which layers of oil paint are built up without drying in between.

Liepke is an American, b. 1953, in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.