01 Jul Telluride Gallery of Fine Art: Best & Murrill Featured, Official Opening is Art Walk, 7/5

Telluride Arts’ First Thursday Art Walk is a festive celebration of the art scene in downtown Telluride for art lovers, community, and friends. Participating venues host receptions from 5 –8 p.m. to introduce new exhibits. Go here to check out all the other shows in town.

The second Art Walk of the summer 2018 season takes place Thursday, July 5, 5 – 8 p.m.

In concert with Art Walk, Telluride Gallery of Fine Art officially opens a major new show featuring the work of painter Diane Best & sculptor Gwynn Murrill, displayed together for the first time.

Please scroll down to learn more about the work and this unique pas de deux: “Stillness in Motion,” which runs through July 17.

Iceberg, Andvord Bay, Antarctica 36X72, Diane Best.

Coyote, Gwynn Murrill.

At one point in her life as a commercial artist, painter Diane Best created an album cover for Madonna. The record company chose a photograph for Like A Virgin instead of Best’s image, but Madonna said she liked both works (according to Best during a Gallery interview). Now her own photographs, the ones the artist used to use only to hold place memories, are selling like hot cakes alongside her increasingly abstract acrylics – with echos of Van Gogh, Turner, Constable, even Ad Reinhardt’s spiritual scapes. (See “Galisteo,” “Telluride Whiteout,” “Mosaic Canyon Sky,” “Glacier, Antarctica.”)

Galisteo, Diane Best, acrylic on canvas, 36X72.

Telluride Whiteout, 2018, acrylic on panel 36 X72.

Glacier, Antarctica 36X72.

Mosaic Canyon Sky, 50X40.

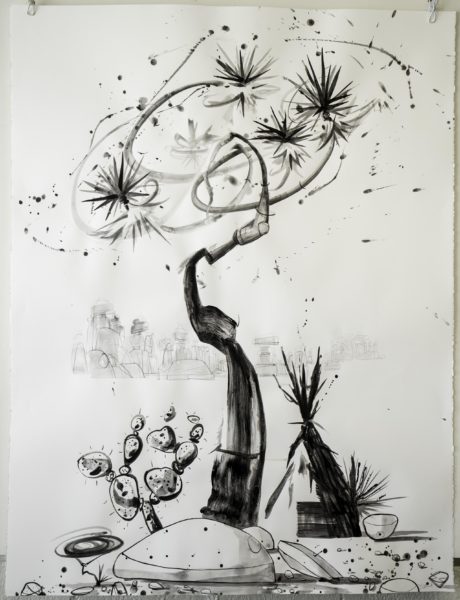

Best’s wonderfully whimsical black, mixed-media paintings of the trees near her home, near Joshua Tree, are quirky meditations on a favorite theme and notable for fact the artist’s inspired lines and spatters speak of strong intentions and also connections that convey pride of place, hope and, yes, fear too that it might all go away.

“Painter Diane Best is most well known for landscapes that evoke the contemplative atmosphere and extremes of form and experience found in the American desert. In this show, several studies of Joshua trees reveal the artist’s precise and painstaking observation of nature. Her large, wide oil-on-canvas paintings offer an expansive and vast sense of place, where looming storms and dramatic transformations are inherent to the environment. The exhibition includes recent work reflecting the artist’s travels to Antarctica, whose stark and visually arresting forms are captured in two nighttime scenes. In ‘Antarctica Berg,’ blocky white ice formations at the base of mountains, illuminated by moonlight, are rendered as painterly, almost abstract forms, inviting the viewer to consider the ambiguity between the natural and the abstract. In addition, Best has recently created two paintings of the Telluride area itself that appear in the show, calling attention to the unique beauty and geography of this place. ‘Telluride Whiteout’ captures an extraordinary moment as thick cumulus clouds move across the panorama of the sky, creating a visual slice of air through which the snow-capped mountains are visible. While this glimpse of mountain occupies just a fraction of the canvas, the immensity of their forms is clear,” explains the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art.

“After 45 years of painter, I am like the Zen master who spent a life time trying to draw a perfect circle. I am learning to let go, to be freer on the canvas,” Best explains. “And when I am in the zone making art, I am not thinking of anything else. The process is a meditation.”

As a landscape painter, Best falls in the lineage of no frills with John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, who defined the supreme achievements of landscape painting in Europe in the first half of the 19th century, in part by simply exiting shepherds, dryads and fairies from their work. The artist’s later work is particularly aligned with Turner’s endless rhetoric of abstract, sublime effects (as above).

Trout Lake, Telluride, 24X48.

Valley Storm, Telluride 2018, 24X48.

The prolific and widely gifted Best is now also making non-narrative films. The progeny of Phillip Glass’s “Koyaanisqatsi,”1982?

Equally talented, sculptor Gwynn Murrill, who has been fashioning animals since the 1970s, studied as a young woman with some of the giants of the Sixties California art scene: Tony Berlant of intricately detailed, riotously colorful collage fame; Richard Diebenkorn of the iconic Ocean Park series of geometric abstractions of an urbanscape; and minimalist John McCracken. But it was the beauty and delicacy of Donatello’s “David,” which Murrill saw at the Bargello in Florence when she was a student at the American Academy in Rome, that turned the tide for the formative sculptor.

The splendid bronze portrait of a young David triumphantly stepping on Goliath’s severed head while holding a sword, anchored by the negative space around it, became a kind of muse for Murrill, who believes the space around and between her primary subjects are artistically relevant and very important shapes – and that includes her pedestals.

Donatello’s “David” inspired contemporary sculptor Gwynn Murrill as a young student studying in Rome.

“…Her work often features animals perched or elevated, in some cases upon an element from nature such as a branch, in others on a more abstract form suggesting a slab of rock or a base or stand. In ‘Wolf I on Short Base,’ a wolf appears in mid-step, vigorous yet streamlined. The animal’s elevation on a simple slab calls attention to its worthiness as an artistic subject and to the graceful animal form itself. The majestic ‘Hawk on Branch’ stands out with its sweeping form and naturalistic representation of the bird of prey. From its high perch, with feet steadfastly planted on a small circular platform, we are invited to consider an elevated view and a closer look at the delicacy, grace, and majesty of everyday creatures. Simplicity of form in Murrill’s work is complemented by her careful attention to surface and texture…,” explains the Gallery.

Hawk on Branch, Gwynn Murrill

About her sculptures representing some of the animals of the California countryside, Gwynn Murrill states: “My interest lies in using my chosen subject as a means to create a form that is simultaneously abstract and figurative. I enjoy the challenge of trying to take the form that nature makes so well and derive my own interpretation of it.”

Abstract in what way?

Look closely: eyes and ears of the subjects in Murrill’s menagerie are unfinished. Hooves are not well defined. No one has fur either.

Abu Cat, Murrill.

Deer 3, Murrill.

“Gwynn stops when she has caught the spirit,” explains artist-historian-teacher and close friend of Murrill’s, James Hayward, (also curator of a number of the wonderful past shows at the venue since Ashley Hayward and Michael Goldberg took over from the Thompsons)

Murrill is a painter and ceramicist too – but so far that part of her artistic identity remains closeted. So is an emerging body of work, a total departure from the signature pieces on display – and from Murrill’s body of work over the past four+ decades.

“ I am not an add-on sculptor. I am carver, a reductivist. My favorite thing is carving. For years, however, I’ve tried to make some work funky, but my pieces always come out refined. However, now I am creating a new body of work, which is figurative. The emerging forms feel more primitive than my animals. They are definitely goofier – and sexual.”

From a rocking-horse, a very early piece, to rocking out.

Wait for it.

In 1971, an article in ARTnews posed a controversial question: “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?”

Great artists defined as those who establish ideals for subsequent artists. There were no woman on that list back then, which did include the likes of Delacroix and Picasso.In fact, the names of women of the period, roughly when Best and Murrill were getting their mojos working, got out there largely because they were linked to famous men: for one example, Lee Krasner, who did become a big name, but not until the 21st century, was married to Jackson Pollack.

The issue seemed to be less about the glass ceiling of the business world and more about absent floor space – no room at the IN.

Not so at this blockbuster show – “Stillness in Motion” – at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art, which turned over its floor – and walls – to Diane Best (what’s in a name? Get it? Best.) and Gwynn Murrill, whose work is being shown together for the very first time.

Beside the accident of gender, on the surface what the women share is a love of the natural world: Best paints landscapes where man’s notable absence is, at times, footnoted only by a section of road; Murrill fills those empty spaces with her critters, the wild things she tames in bronze, wood and marble.

But another good reason Ashley Hayward might have elected to pair Best and Murrill lies beneath the surface, in the spiritual connection between the two artists.

What we mean by that is in a world where we have become so disconnected from each other, from nature and from the aesthetic and/or spiritual, both artists recognize the inter-relatedness of all things. The moments they choose to freeze and preserve in the amber of their work – a storm in a desert; a coyote stalking – are imbued not just with kinetic energy, but also with an understanding of the heart that allows us to feel empathy with whatever is being depicted.

We don’t just see Best’s stark deserts of sand or ice. We perceive those places as fragile and precious, something to be protected and preserved.

(In fact, Best was recently hired by the Mohave Desert Land Trust to create a tribute to Bear’s Ears, a favorite Telluride destination, now under assault by Pruitt & Co.)

Stovepipe Wells Dunes 4, 2008, acrylic on panel, 24 X72

In Murrill’s work, we don’t just see bear perched on a pedestal. We perceive his quiet contentment in the moment threatened by imminent challenges to his domain – read climate change and developers chasing fossil fuel.

Beat Stand, Murrill.

Could come from anywhere.

But it is likely coming…

Bottom line: Through the informed imaginations of these two brilliant woman, “Stillness in Motion” gives voice to the content of our psyches, both the joy and the existential angst we experience almost simultaneously when confronted with beautiful living things: environment or animal.

And because the artists are so confident of their gifts, they have no need to shout.

In fact, elegance and restraint (or knowing when enough is enough and so when to stop their creative processes) are other variables that also make the coupling make sense.

“…Best and Murrill have each been steadfastly dedicated to their natural subject matters for decades. Both describe their work with a straightforward simplicity, as if so enraptured in nature itself, that there is no choice but to depict it. Shown together for the first time in Stillness in Motion , the two artists share an affinity for exposing the multifaceted conditions of the natural world and the haunting stillness that exists in the wild…,” wrote Lindsay Preston Zappas in an essay about the show, continuing, “For both artists, the natural world is dual a source of comfort and fear—a space that is constantly in flux. The unknown aspects of the natural world are perhaps those that beckon each artist to continue mining their subjects, searching to unearth unseen nuances. In short, each artist is adept at coaxing out the essential nature of the creature or landscape, aptly depicting the multiplicity that exists in all things. Shown together, Stillness in Motion portrays the rich complexity of the natural world, as a source of life and inspiration, but also its potential isolation, and despair. What remains is at once a celebration of life, and an acknowledgement of existential dread. We find ourselves somewhere within these dualities, searching for a moment of stillness in a chaotic world. “

What else the two artists share is predestination: both were born to roll the way they roll.

Best and Murrill both started making art at a tender age.

Best’s mom was a folk musician who attended Ratcliffe (back then Harvard’s sister school); her dad went to MIT and worked on the first major computer project. Both told their daughter she could do whatever she wanted to do. And what Best wanted to do was become an artist. The die was cast when a fourth-grade teacher gave her promising student a drawing of a fish with polka dots.

At private school at the Abbot Academy (the sister school of Andover), Best majored in art. She attended Stanford for awhile, but found the requirements of the art department a drain: she had been there, done that.

Instead, Best finished her formal education at the San Francisco Art Institute, before moving to LA and building a robust career as a commercial artist. However, a move to the solace of the desert near Joshua Tree changed all that. The desert, now including the ice deserts of Antarctica, became Best’s muse – and cause.

In contrast, Murrill’s family was not nearly as supportive of her genius. Told wanting to be an artist was fine as long as she had a real job, Murrill was sent to secretarial school. And not just any secretarial school, the cat’s meow of such institutions: the white-gloved world of Katherine Gibbs.

“I learned how to waste time,” the artist quips.

Murrill left New York and headed for the Left Coast, earning a degree in painting at UCLA before immersing herself in Venice art scene and its mafia, where she found she preferred working in 3D.

Murrill had her first show of sculpture in 1972.

Innate talent and years of training, formal and on the job, means both Best and Murrill are technically proficient, now at the top of their game and flying faster and looser.

In addition to elegance of execution, however, one more thing that binds the two women in the “Stillness of Motion” is the soulful part that comes through in the work.

That is a thing, an innate gift, that can’t be taught.

Wearing their souls on the sleeve of their work is yet another gift this pas de deux has to share with the public.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.