06 May TIO NYC: “The Seafarer”+ A Chelsea Afternoon

On yet another fine day in the Big Apple, on stage and on the walls of the many galleries in Chelsea we visited, we found the lines between reality and fantasy, fact and fiction, past and present blurred. And, as always, the Devil was in the details.

Tickets to “The Seafarer” (just through May 24) here.

Matthew Broderick, left, as Mr. Lockhart, and Andy Murray as Sharky, a man trying to stay away from the bottle, in Conor McPherson’s “The Seafarer.” Credit Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

Perhaps, as Fydor Dostoevsky suggested, “The devil does not exist, but man has created him, he has created him in his own image and likeness.”

Enter Mr. Lockhart.

Or Matthew Broderick as Old Scratch himself – in this incarnation, tricked out as a diabolical Dapper Dan in the borrowed body of the dead Lockhart.

Mr. Lockhart plays cards for keeps with a cast of alcoholic losers and bruisers in Conor McPherson’s real and surreal, mordantly funny, brilliantly architected play “The Seafarer,” which is all about the possibility of hope and redemption even among its protagonists, all lost souls.

In a chilling monologue, Mr. Lockhart gleefully describes home sweet home as an eternity in a cold sea of isolation. It is a description that echoes themes of the 10th century Anglo-Saxon elegy “The Seafarer” – but in a way infinitely more horrible to contemplate.

Director Ciarán O’ Reilly was either ruthlessly exacting or he gave his brilliant cast a very long leash, either way, he gets natural and very engaging performances from each of his talented actors, including Broderick – though, for me, the actor’s surprisingly small stature made the towering role of His Satanic Majesty a bit of a stretch. Quibble aside, the boffo ensemble – including the character of the wind, which howls louder as the tension grows – delivered a fully woke performance in this top-drawer production.

From left, Mr. Broderick sharing a drink with Tim Ruddy, Michael Mellamphy and Colin McPhillamy in a scene from the production. Credit Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

Operating on both a literal and metaphorical plane – for example, the idea of “spirits”– ours and what comes out of a bottle – and thus playing with the notion of a glass half full or half empty, “The Seafarer” amuses as it chastens us to never lose sight of what is in front on our eyes – or at least, never lose our glasses.

Our party, for one, lustily drank it all in.

Here is a full review from Variety.

The Whitney and Chelsea: What not to miss:

The most iconic image in the Grant Wood show, “Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables” at The Whitney Museum is not too surprisingly the double portrait of a pitchfork-wielding farmer and a woman commonly presumed to be his wife (but more likely his daughter?) entitled “American Gothic.”

American Gothic by Grant Wood, courtesy The Whitney.

Easily one of the most recognizable images of the 20th century, “American Gothic” represents an idea, perhaps an ideal, of the way we were – or at least some of us living in rural American: plain, simply spoken and openly honest, hard-working, rugged individuals.

“Death on the Ridge Road,” 1935, oil on composition board. (Williams College Museum of Art/Copyright Figge Art Museum/Licensed by VAGA).

But perhaps the most revealing (of the darkness beneath Wood’s surface) and easily one of the best and among the surprising images in the sprawling show is “Death of Ridge Road,” a surreal and forbidding landscape depicting two passenger cars heading up a steeply inclined road as a large red truck comes hurting toward them around a blind curve. In the background, an angled wedge of dark storm clouds release torrents of rain.

“…In it, we discover the coexistence of different forces and potentials in Wood’s Americana, lines and curves as unresolved in their intersections as our sense of both the past and future,” wrote The Washington Post.

The exhibition brings together the full range of Grant Wood’s art, fills in around the edges of “American Gothic” to reveal the artist from his early Arts and Crafts decorative objects to his Impressionist oils through his mature paintings, murals, and book illustrations – and the artist as a complex, sophisticated man whose image as a farmer-painter was as mythical as the fables he depicted in his work.

According to the Whitney: “Wood sought pictorially to fashion a world of harmony and prosperity that would answer America’s need for reassurance at a time of economic and social upheaval occasioned by the Depression. Yet underneath its bucolic exterior, his art reflects the anxiety of being an artist and a deeply repressed homosexual in the Midwest in the 1930s. By depicting his subconscious anxieties through populist images of rural America, Wood crafted images that speak both to American identity and to the estrangement and isolation of modern life.”

For us, Wood’s later fantasy landscapes, stripped of the precious details of earlier similar works, were the most compelling in this surprising show.

A full review from The New York Times here. (Through June 10.)

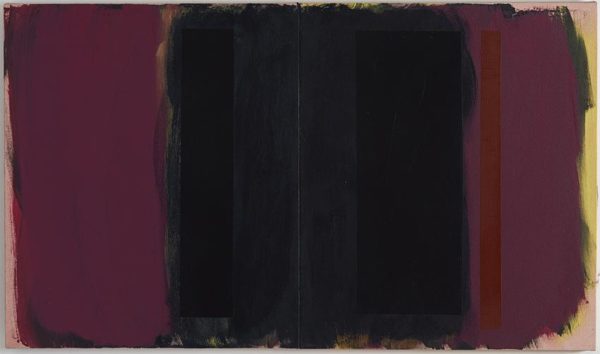

And while we are on the subject of artists from rural America, according to his biographers, Doug Ohlson socialized with famous Abstract Exers such as Robert Motherwell, but he created restrained, geometric works inspired by the saturated swaths of open sky and flat land in Iowa, where he was born during the Great Depression.

As New York Times art critic Roberta Smith has observed, “The staple of his formal vocabulary was repeating vertical bars that seemed, increasingly, to levitate before clouds of vibrant contrasting color.”

Ohlson’s elegant show, “The Dark Paintings” circa 1990, is up at the Washburn Gallery, 177 10th Avenue, through June 1.

There is a whole lot going on – ghosts and gods, monsters and maenads oh my – in Inka Essenhigh‘s colorful, slick-surfaced, fanciful, figurative abstractions, now on display at the Miles McEnery Gallery, 525 West 22nd Street, through May 25.

Image, Inka Essenhigh, courtesy Artsy.

In his 2017 show, “Portraits and Perennials” at the DC Moore Gallery, 535 West 22nd Street, Robert Kushner extended the boundaries of his compositions, infusing his iconic, organic imagery with vibrant color and patterns.

But his new paintings, “Reverie: Dupatta-Topia,” up through June 16, are a radical departure from that work. Here the artist appears to be looking over his shoulder back to some of his earliest paintings on fabric from the 1970s and 80s.

This new and visually exciting body of work, created by collaging fabric to canvas before adding paint and gilding, all texture and exuberant color, shows the artist tapping into issues of embellishment and beauty in art ever-present in Kushner’s paintings over the years.

The fabrics, mostly silk, come from India, Japan, and Uzbekistan. The flamboyance, sparkle, elegance and technical mastery of the materials, particularly the Indian embroideries known as dupattas, are endlessly fascinating, deeply engaging, mashing up, as the work does, different cultures and different times, while remaining firmly grounded in the present.

Although Chun Kwang Young began his career as a painter, he started to experiment with paper sculpture in the mid-1990s. Over time the work evolved in complexity and scale.

The development of Chun’s signature technique was sparked by a childhood memory of seeing medicinal herbs wrapped in mulberry paper tied into small packages.

The images, with an all-over, muscular Abstract Expressionist feel, awere created by subtly merging the techniques, materials, and traditional sentiment of the artist’s Korean heritage with the conceptual freedom he experienced during his Western education.

Chun’s new work, “Aggregations,” is up through June 16, at Sundaram Tagore Chelsea, 547 West 27th Street.

While the natural world plays a profound role in the work of Mathias Meyer, up now through May 25, at the Danese Corey Gallery, 511 West 22nd Street, the artist establishes a delicate balance in his portrayal between realism and abstraction.

Within Meyer’s real and imaged world, water is the through line – lakes, ponds, waterfalls – and the flora they all contain.

Both mysterious and revealing, the water’s surface reflects its surroundings and simultaneously offers a glimpse into a realm below – you know, like in Monet’s “Waterlilies” series, his iconic paintings from his time at Giverny – but here rendered here by Mathias even more abstractly: enigmatic, distorted images of decomposing tree trunks emerge from the depths, while reeds, water lilies and grasses thrive above on these beguiling canvases.

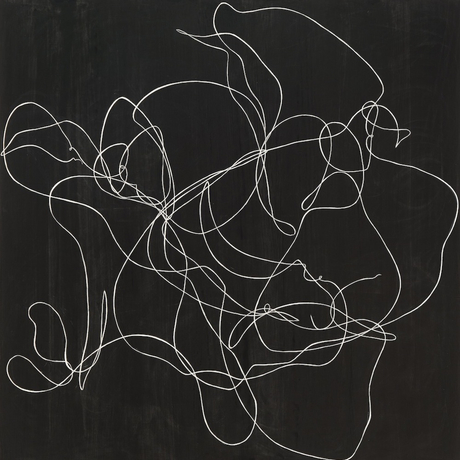

It can wind across a paper or a canvas, turn back on itself forming curls (as in da Vinci) or aggregate to form shape, body or landscape. In whatever transformation, lines can emit and elicit powerful emotions – as they do in the simply elegant work of artist Elliott Puckette, where less is definitely more.

The delicate, ethereal paintings, up now through June 9 at the Paul Kasmin Gallery, 297 Tenth Avenue, are a continual exploration of the sensuous line, the artist’s central formal element, her insistent subject – and her obsession.

Puckette creates her linear abstractions or rather shapes that morph between recognizable forms back to abstraction by mapping out the work with chalk. Then the artist painstakingly etches it into the gesso-and-ink surfaces of her pieces with a single-edge razor blade.

This new body of work at Kasmin was inspired by lines in nature such as those suggested by brambles and branches.

The sculpture of Ursula von Rydingsvard is featured at Galerie LeLong & Co., 528 West 26th Street, through June 23.

Over 40 years and counting, von Rydingsvard evolved into one of the most influential postwar sculptors working today, best known for creating large-scale, often monumental sculpture from cedar beams, which she painstakingly cuts, assembles, and laminates, finally rubbing powdered graphite into the work’s textured, faceted surfaces.

Her signature abstract shapes refer to things in the real world —vessels, bowls, tools, and other objects — each revealing the mark of the human hand, while conjuring natural forms and powerful forces.

In recent years, von Rydingsvard has explored other mediums in depth, particularly bronze, continuing to expand upon her unique artistic vocabulary.

This review on artnet is spot on. It is entitled “The Sorceress of Cedar”:

Ursula von Rydingsvard’s dense, eccentric, craggy sculptures fascinate me, yet I can’t remember any art that has made me so strangely uneasy. Her mammoth constructions quiver with power and evocative, disturbing contradictions. These cedar creatures, their scarred and striated surfaces frequently darkened with rubbed-in graphite, are monumental yet intimate, crude yet delicate. Von Rydingsvard is an artist who works on a dauntingly heroic scale while the underlying content of her pieces is intensely personal, even haunted by her memories, for she is a veteran survivor of real struggle.

It’s been widely noted that she was born on a German farm to a Polish mother and Ukrainian father forced to work as agricultural slave laborers under the Nazis during World War II…

The work of Cayce Zavaglia is up through June 2 at the Lyons Wier Gallery, 542 West 24th Street.

“Southerly” is series of hand-embroidered portraits of the artist’s childhood friends and their families in Australia, a modern take on the pointillism of Seurat.

Zavaglia’s work touches on the universal immigrant experience of friends assuming the roles of absent family members. They are reflections on the evolving definition of the concept of “family.”

Below is a statement from this talented artist.

“I was originally trained as a painter, but switched to embroidery 16 years ago in an attempt to establish a non-toxic studio and create a body of work that referenced an embroidered piece I had made as a child growing up in Australia. My work focuses exclusively on the portraits of friends, family, and fellow artists. The gaze of the portrait toward the viewer has remained constant over the years and in my work…as has my search for a narrative based on both faces and facture. The work is all hand sewn using cotton and silk thread or crewel embroidery wool. From a distance they read as hyper-realistic paintings, and only after closer inspection does the work’s true construction reveal itself.

Over the years, I have developed a sewing technique that allows me to blend colors and establish tonalities that resemble the techniques used in classical oil painting. The direction in which the threads are sewn mimic the way brush marks are layered within a painting which, in turn, allows for the allusion of depth, volume, and form. My stitching methodology borders on the obsessive, but ultimately allows me to visually evoke painterly renditions of flesh, hair, and cloth.

A few years ago, I turned one of my embroideries over and for the first time saw the possibilities of a new image and path for my work that had been with me in the studio for so long but had gone unnoticed. It was the presence of another portrait that visibly was so different from the meticulously sewn front image…but perhaps more psychologically profound. The haphazard beauty found in this verso image created a haunting contrast to the front image and was a world of loose ends, knots, and chaos that could easily translate into the world of paint.

This discovery led to a “return to paint” in my work and the production of a series of intimate gouache and large format acrylic paintings of these verso images. Highlighting the reverse side of my embroideries, which historically and traditionally has been hidden from the viewer, has initiated a conversation about the divergence between our presented and private selves. The production of both Recto and Verso images is now the primary focus of my studio work.”

Michal Rovner’s (b. 1957, Israel) work – video, sculpture, drawing, sound and installation – has been exhibited in over 60 solo exhibitions including a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art, the Israeli Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, the Jeu de Paume, and the Louvre.

Pace Gallery, presents Rovner’s “Evolution,” a solo show dedicated to the artist’s pioneering work. The New York show follows a celebrated exhibition in Palo Alto earlier this year. On view at 537 West 24th Street through June 23.

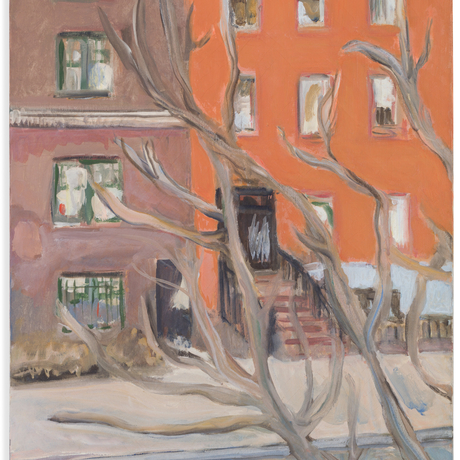

For a walk down memory lane to kinder, gentler times, “Jane Freilicher, 50s New York” is on display through June 9 at the Paul Kasmin Gallery, 293 10th Avenue.

The presentation is the first to focus on Freilicher’s paintings from the 1950s, a body of work critic (and painter) Fairfield Porter termed “traditional and radical.”

The show includes early still lifes, portraits and the studio views that elucidate the artist’s characteristically deft balance of interior and exterior.

Hailing from the 1950s and painted within various studios in lower Manhattan, the works are evocative of a downtown milieu that has since come to represent the period’s golden age of spirited, improvisational artistic freedom. They articulate Freilicher’s enduring influence: her steadfast observation and intuitive realism are detectable within the work of a number of painters working today.

Over a six-decade career, Freilicher quietly painted in direct contrast to the heroic and gestured angst of Abstract Expressionism, the industrial starkness of Minimalism, and the broad sweeping cacophony of Pop.

She painted in the same spirit and dedication as Bonnard and Matisse: a subtle and unrelenting observation of domestic life.

In a 1975 review, John Ashbery described Freilicher with “Obviously she paints what she sees, but it happens that she sees a lot.”

Featured amongst the vivid array of the artist’s cityscapes are the tough iron zig-zags of fire escapes, plumes of wispy grey emerging from ConEdison smoke stacks, the quintessential red-brown of New York City apartment blocks, and the almost-abstract configurations to which these elements conspire.

Freilicher, who was born in Brooklyn and lived and worked in Greenwich Village for the whole of her life, was a leading figure of the New York School scene of the 1950s and 1960s. In his poem ‘A Sonnet For Jane Freilicher,’ Frank O’Hara describes “Jane whose paintings like a stone / are massive true and silently risqué.”

David Hockney (b. 1937, Bradford, England) has produced some of the most vividly recognizable images of this century. His ambitious pursuits stretch across a vast range of media, from photographic collages to full-scale opera stagings and from fax drawings to an intensive art historical study of the optical devices of Old Masters.

Hockney received the gold medal for his year at London’s Royal College of Art in 1962. The artist had his first one-man show in 1963 at the age of 26, and by 1970 the first of several major retrospectives was organized at Whitechapel Gallery, London, which subsequently traveled to three additional European institutions.

“P&J LOOKING” 2014

ACRYLIC ON 2 CANVASES (48 X 36″ EACH)

48 X 72″ OVERALL

© DAVID HOCKNEY

PHOTO CREDIT: RICHARD SCHMIDT

“Some New Painting (and Photography),” a blockbuster show now up at the Pace Gallery, 508-510 West 25th Street through May 12, is Hockney’s first exhibition of works completed since his return to Los Angeles from England, where he spent a decade pictorially exploring the East Yorkshire landscape of his youth.

.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.