20 Sep TIO NYC: The Other, Islam, Modigliani & More

According to Dr. Shadi Hamid in his new book Islamic Exceptionalism: How the Struggle over Islam Is Reshaping the World, the failure of democracy to take root in the Islamic world is not about the election of Islamists. It is the sheer panic their ascent to power prompts among secularists, who react by staging major coups.

Dr. Shami Hamid spoke at an event sponsored by Network 20/20.

It has been five years since the Arab Spring began, years of chaos, coups, repression, terrorism, and war. Over that time, American policy toward the MidEast has vacillated between support for the ideal of democracy, dismay upon discovering that democracy brings Islamists to power – and drone warfare. Few understand our policy toward the region and further, it is not clear we actually have one.

One of our first outings in the Big Apple was attending a lecture by Hamid about “How the Struggle Over Islam is Reshaping the World.” The event was hosted by Network 20/20, a nonprofit supported by one of our dearest friends.

Network 20/20 is an independent organization that builds foreign policy understanding in young and mid-career leaders by “connecting people and clarifying foreign affairs.” For more on the work of Network 20/20, go here.

Hamid suggested that to understand Islam we have to accept the fact the religion differs from others in the relationship between “church” and state. There is no separation, religious leaders are also secular leaders. The prophet Mohammed was a religious leader, a politician, head of a proto state and a state builder, unlike Jesus, who was a dissident and separate from the state. The Koran is not just the word of God; it is God’s actual speech. Unlike the Bible, it is wholly of divine origin with no human authorship. Therefore Islam of yesterday and today remains resistant to the march secular, rational, liberal, democratic end.

Ultimately Hamid’s conversation comes down to an understanding or better, our misunderstanding, of The Other or Not Us, a space Muslims have occupied relative to the West and within the US for years, now more than ever.

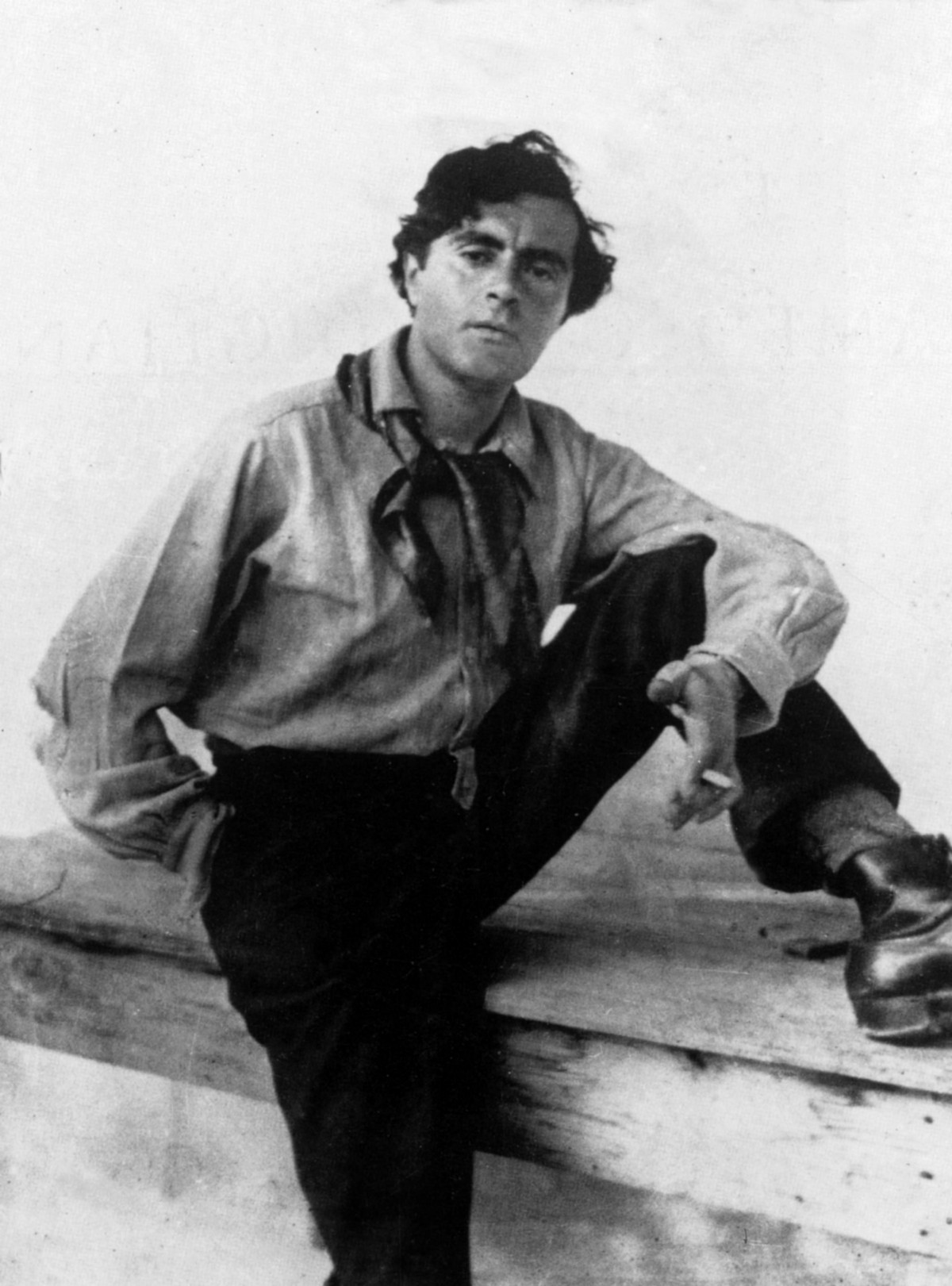

The Other is also, somewhat surprising, the through line of one of the best museum shows in New York this month, “Modigliani Unmasked” at the Jewish Museum, an exhibition which examines the life and times of the celebrated artist Amedeo Modigliani shortly after he arrived in Paris in 1906, when the city was still roiling with anti-Semitism after the long-running tumult of the Dreyfus Affair and the influx of foreign emigres.

Amedeo Modigliani could have passed as French but chose to identify himself as a Jew. His cultural identity deeply influenced the artist’s work.

The exhibit includes about 150 works from the Alexandre collection, as well as a selection of Modigliani’s paintings, sculptures and other drawings from collections around the world.

Lola de Valence, a Parisian entertainer morphs into an African mask in the hands of Modigliani.

Collectively the works illuminate how Modigliani’s heritage as an Italian Sephardic Jew and his response to the social realities he confronted in the artistic melting pot of Paris helped forge a complex cultural identity that rested in part on the ability of Italian Jews historically to assimilate and embrace diversity – though Modigliani chose not to. Instead, this defiant Other blew raspberries at the dark and prevailing sentiment of the day – France was considered the most anti-Semantic country in the world at the time – announcing himself by name first, then always adding “and I am Jew.”

Complementing Modigliani’s own work is art representative of his various multicultural influences — African, Greek, Egyptian and Khmer — images that profoundly inspired the young artist during this lesser-known early period. Is it possible Modigliani’s signature, reductive, highly stylized faces and forms – his friends and lovers, for example, resemble Egyptian deities and African masks – mark the artist’s attempt at summarizing a universal ideal that he saw as crossing time and cultures?

More art:

Esperanza Spalding’s first Telluride appearance was 2007 for Winter Jazz. Those of us who knew Telluride Jazz Festival’s long-time impresario Paul Machado knew the man has an eye for the ladies. His special gift was to catch rising stars before they reached their zenith: violinist Regina Carter; guitarist Badi Assad; chanteuses Diana Kral; Jane Monheit; and Lizz Wright to name a few of Machado’s picks early in their careers.

The story of Esperanza Spalding is a rags-to-riches-tale, an American dream come true, because a smart single mom recognized she had a gifted daughter who thought – and played – out of the box. Years later, the jazz bassist/singer has clearly earned the respect of her peers. And one of her major fans happens to be President Obama.

Matisse in Spalding’s curated show.

In 2011, Spalding took the Grammys by storm, winning Best Artist, trumping popsters Justin Bieber and Drake, plus bands Mumford & Sons (Telluride Bluegrass Festival, 2010) and Florence & The Machine.

The name “Esperanza” means “hope” in Spanish, but the lady is way beyond hope. By the ripe old age of 26, the beautiful – she’s a mix of Welch, native American and African American – petite bassist/vocalist with the towering Afro had arrived.

On bass, Esperanza Spalding’s tone is rich and beautiful. Once outside the beat, she manages to stretch and suspend it, while still contributing to the evolution of the melody and harmony of her band when she is not going solo. Performing a solo, one critic described her as “a master of velocity.” When Esperanza’s singing is wordless, the sound is reminiscent of Flora Purim singing on Chick Correa’s records.

Spalding told me years ago during our first interview: “I don’t have the most sophisticated voice, but I do have good intonation and singing feels very natural: What comes out, comes out. It takes energy to compose and playing bass is physically demanding. For me, singing is like writing a letter to a close friend or loved one. You don’t have to correct your spelling and grammar. What’s important is the care and feeling you express.”

That was back in the day when the brashness of youth was burnished with an emerging genius.

Recently the now internationally renowned Esperanza Spalding guest-curated a show now on display at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, housed in the former Carnegie family mansion. (On view though January 7, 2018)

For her presentation, Spalding created thought-provoking juxtapositions among objects to show how material evolves into different forms as new designers adapt them for their own locales and cultural functions, organizing nearly 50 objects—encompassing drawings, prints, textiles, jewelry and product design—into eight groupings around themes related to evolution and transformation.

Spalding also recorded original music for the exhibition with Argentine musician and composer Leonardo Genovese, which plays in the gallery.

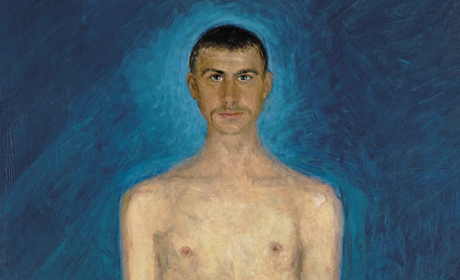

The Neue Galerie features the work of one of the best Austrian painters you never heard of: Richard Gerstl, The show is the first museum retrospective in the United States devoted to the work of the Expressionist (1883-1908).

Ricahrd Gerstl, a troubled, but gifted artist.

Gerstl was an original whose psychologically intense figure paintings and landscapes constitute a radically unorthodox oeuvre that defied the reigning concepts of style and beauty during his time, embodied by the work Gustav Klimt, key examples of whose work, including Woman in Gold, are housed in the Neue’s collection.

The longstanding secrecy surrounding Gerstl’s dramatic and untimely suicide at the age of 25, and the scandalous love affair that preceded his death, serve to magnify the legend that has grown around this lesser known, but influential member of Vienna’s artistic avant-garde at the turn of the 20th century.

Schonberg family, Richard Gerstl.

Here is what Roberta Smith of The New York Times had to say about the show:

Any review of the Austrian painter Richard Gerstl must first get his sensational suicide out of the way. On Nov. 4, 1908, barely 25, Gerstl burned an unknown number of papers, drawings and paintings and then managed to both stab and hang himself in his Vienna studio.

He was isolated and distraught: His affair with Mathilde Schoenberg, wife of his close friend, the modernist composer Arnold Schoenberg, had been discovered in late August by the injured party himself. Gerstl had been instantly banished from the couple’s loyal, close-knit circle, the only artistic family he had ever known. Even so, the small retrospective at the Neue Galerie exudes an irresistible energy and optimism end to end. Gerstl had unlimited faith in both the varied expressive powers of oil paint and his own abilities to summon them.

Gerstl’s art was never exhibited in his lifetime, and this is its first museum solo show in the United States. After his death his family packed away what remained, also disguising the cause of death. In 1931 his brother Alois, whose portrait is in the Neue show, took two small paintings to the art dealer Otto Kallir, who mounted an exhibition in Vienna. This tale is chronicled in the catalog by his granddaughter, Jane Kallir, a director of the Galerie St. Etienne, which her grandfather opened in New York in 1939 after fleeing Austria.

Born in 1883 in Vienna, Gerstl seems to have been a natural rebel, albeit one always supported by his wealthy family. A devotee of music and a voracious reader, he was expelled from private schools and art academies alike, and was an outsider to the Viennese modernists and their leader, Gustav Klimt, whose work he found artificial and decorative. Gerstl was after the immediacy of paint on canvas and of life itself, both its inner and outer purpose.

Gerstl is frequently referred to as the first Austrian Expressionist, since his work developed slightly ahead of that by the somewhat younger Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele. But at the Neue, that characterization ultimately feels too small and neat. In this show, which was organized by Jill Lloyd, an independent curator, Gerstl is constantly on the move, striking out on his own, and then retreating to familiar territory.

Over his brief six-year career, he pursued a range of styles, including a sober realism befitting portrait commissions but enlivened by texture and chromatic daring; a somewhat stiff, regimented Impressionism; a scaled-up airy pointillism; and a loose Post-Impressionism indebted to Munch and Van Gogh, whose influences run throughout his work. Most startling is an unprecedented Expressionism that reveled in paint’s sheer materiality, achieved with wide, loaded brushes or a vigorously wielded palette knife…

“Sonic Arcade: Shaping Space with Sound” is a multi-component exhibition featuring interactive installations, immersive environments, and performing objects that explore how the ephemeral and abstract nature of sound is made material, all on display on floors and the landings between floors at the Museum of Arts and Design.

The show is great if you are in the mood to channel your inner three-year-old – or if you have an extra to bring along.

Recommended eats:

Trattoria Dell’Arte, 900 7th Avenue, Hall, is a Tuscan trattoria with a neighborhood scene, Italian art on the walls and an antipasto bar. Chef Tony Acinapura knew my friend, so we were treated to whatever he felt we should taste., including a terrific mushroom risotto. But the regular menu is great as is the vibe and the location right across the street from Carnegie Hall could not be better if you find yourself in Midtown.

Ashoka, 489 Columbus Avenue, between 83rd and 84th streets, features excellent, authentic Indian food and jazz on weekends. A take-out menu too.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.