11 Jul The Trials of Modern Manhood

We empathize with women trying to be superwomen, juggling family, home and office. But men? According to a recent article by Emily BoBrow which recently appeared in The Economist, yes, men too. Traditional ideas of masculinity persist in the workplace, although men are now expected to step up to more of the household honey-dos. The trials of modern manhood appear to be real…. Read on for more.

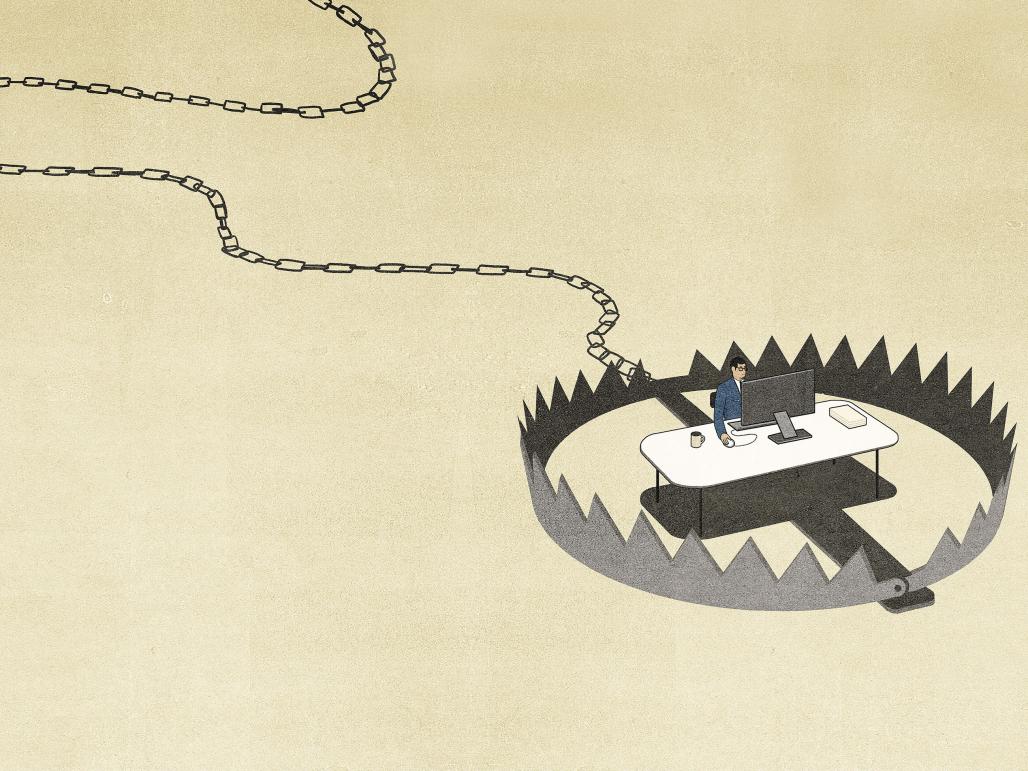

Image courtesy, The Economist 1843.

Nathan, a successful lawyer in Manhattan, hardly seems like a candidate for sympathy. His midtown office is smart, his suit is natty and he earns a decent living negotiating contracts and intellectual-property rights for players in the city’s dynamic entertainment industry. Divorced and in his late 40s, he speaks fondly of his teenage children and is delighted with his fiancée, whom he will marry in a few weeks’ time. His life is good, he assures me, and he is thriving in his career. So it is only with some hesitation that he admits something he has never discussed before, not even with his closest friends: “In the society that I live in, as a professional in New York City, I think it is easier being a woman than being a man.”

This is not to say that being a woman is easy, Nathan hastily adds. He understands why many are frustrated by “the way they are expected to do it all, to have a career and be moms, it’s a whole contradictory bundle of things.” It’s just that few women seem to notice that men, too, are struggling with a similarly burdensome bundle. “As the man, there’s this tacit expectation that I’m going to be the earner and the person who kills bugs and fixes things around the house. At the same time, I’m going to be responsive to feelings and helpful with cooking and the children and those kinds of things.” Unlike his two long-term female partners, who pursued personally rewarding careers that offered enough flexibility to be available to their children, Nathan felt obliged to pursue work that offered a pay cheque large enough to support a family. “For the last 20-plus years I’ve been chained to a desk,” he says. “I’m in a profession that I’m happy to be in, but if I were a 20-year-old and told I could do anything I wanted with my life, I’m not sure I’d be doing this.” Nathan speaks enviously of female friends who decided to leave their professional careers when they became mothers. “They weren’t perceived as failures. If anything, they were told ‘That’s so great, you’re choosing to be a mom, that’s the most important thing in the world.’ That is not an option open to men.”

Nathan is not alone in his misgivings. Between 1977 and 2008 the percentage of American fathers in dual-earner couples who suffered from work-family conflicts jumped from 35% to 60%. The percentage of similarly vexed mothers grew only slightly, from 41% to 47%. Young men who get stuck supporting a family often report high levels of stress and sadness that they aren’t spending more time with their kids.

Because men – and especially white, professional men – occupy a uniquely privileged place in society, Nathan is reluctant to discuss his feelings openly. “I’ve never expressed this to any of the women in my life, and I think it’s best that I don’t,” he says. He is right to be wary. Most conversations about gender inequities characterise men like Nathan as part of the problem. Women around the world may be graduating from college at higher rates than men, but they have yet to achieve similar rates of success in their careers. The uneven burdens of parenthood appear to be to blame. Although men in rich countries spend far more time cooking, cleaning and child-rearing than ever before, their efforts continue to be dwarfed by those of women. In America, for example, mothers devote nearly twice as much time to child care and housework as their male partners. Even couples with grand plans for an egalitarian partnership typically revert to more traditional roles after the birth of a child. A new study of the time-diaries of highly educated dual-earning American couples found that new fathers enjoyed up to three-and-a-half times as much leisure as their female partners, as mothers who worked full time were still stuck with the lion’s share of unpaid labour.

Feminists have long argued that men see little need to help out more at home because they already enjoy all the benefits of marriage and fatherhood without having to put in the extra work. “Even though it’s shifting drastically, marriage is still a pretty good deal for men in terms of the actual labour they capture from their wives,” says Scott Coltrane, a sociologist at the University of Oregon…

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.