15 Apr TIO NYC: Icons, O’Keeffe + Konitz

“Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern,” at the Brooklyn Museum through July 23. Go here to learn more about the jazz club, Mezzrow.

Image, Alfred Stieglitz. Courtesy, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe via Brooklyn Museum.

As a pioneering modernist painter and feminist icon, the lady was OK.

Literally.

She was Georgia O’Keeffe.

Out of the gate (circa 1916) one of the Big Apple’s biggest tastemakers, Albert Stieglitz, is sent the work of a beautiful young graphic designer and fine artist by one of her former classmates. The man is so blown away he decides to hang the images on the walls of his avant-garde Gallery 291, (at 291 Fifth Avenue), also the staging ground for an elite fraternity of burgeoning art world alpha males, among them, Rodin, Matisse, Picasso, Duchamp, and Brancusi. Lots of talent – and testosterone. Heady company for an entrance.

Back then, Stieglitz also purportedly declared “Finally a woman on paper,” words that might well have been a mixed blessing. They opened the door to a highly sexualized interpretation – however true– of O’Keeffe’s work, particularly her florals. Later, reputation and myth secure, the artist rebuked the claim, declaring it said more about the viewer than her artistic intentions.

Black Pansy and Forget-Me-Nots, courtesy Brooklyn Museum.

“I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way – things I had no words for,” she once upon a time explained.

With her serial, in-your-face paintings of flowers, barren landscapes, and still lifes, Georgia O’Keeffe clearly played a pivotal role in the development of American modernism. But her singular, much publicized persona was not simply a byproduct of those signature images. It was carefully crafted, skillfully guarded, and zealously promoted through dress, homes, even the way the lady posed for the camera.

The whole is revealed through the sum of its parts at the Brooklyn Museum’s “Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern.” The lovingly curated show features lovely hand-sewn blouses, bespoke men’s suits, ballet flats, bandanas, jewelry (the OK pin designed for her by Calder), smocks lined up in a neat row like Don Judd’s cubes, and knock-out paintings of pink shells, flowers, animal skulls, and surreal landscapes, including a mountain outside O’Keefe’s window in her Abiquiu home that stylistically and energetically resembles Cezanne’s Mont St. Victoire. There are also photos of the artist by the likes of Stieglitz, Ansel Adams, Philippe Halsman, Yousuf Karsh, Todd Webb, Cecil Beaton, Bruce Weber, Annie Leibovitz, Dan Budnik, and other greats, plus a portrait of the artist by Warhol, natch, all organized by the influential historian of early American modernism, Wanda M. Corn, and coordinated by our guide, Lisa Small, whose day job is Curator of European Painting and Sculpture.

The O’Keeffe show runs through July 23. This unique spin on the artist’s life and work is the opening shot of a yearlong celebration of feminist thinking.

And what exactly does it all reveal about her thinking?

What for example is the takeaway from the dialogue between three delicate blouses and a shimmering painting of canary-yellow autumn leaves (from 1928)? Is the juxtaposition largely meant to point out the connection between the veined surfaces and serrated edges of the foliage and the subtle embroidery of the garments?

Embroidered blouses, 1930,s next to 2 Yellow Leaves, 1928. Courtesy, O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society.

Or is it that and something more?

Something more perhaps that could be explained by O’Keeffe’s roots.

Farms are places where natural disasters destroy crops.

Calves die.

Mortgaged equipment breaks down.

Georgia O’Keeffe was born near Sun Prairie, Wisconsin in 1887, the second of seven children who grew up on a dairy farm.

Farms are austere places where a person learns the value of frugality and hard work.

They engender pride and self-respect and a kind of rugged individualism.

It is a world with little room for gray or ornamentation. Until the sun-drenched palette of the Mexican landscape enters the picture, O’Keeffe’s preferred colors are black and white.

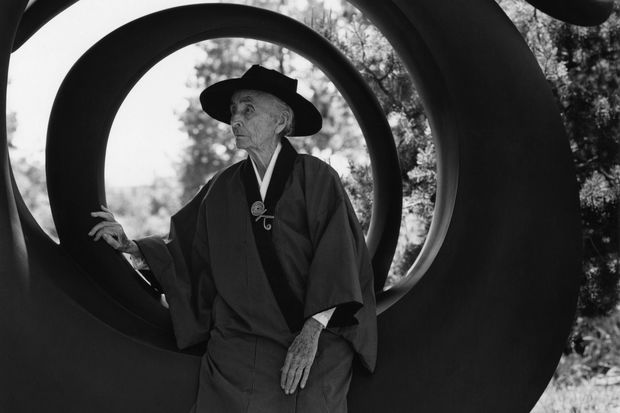

Bruce Weber (American, born 1946). Georgia O’Keeffe, Abiquiu, N.M., 1984. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 in. (35.6 x 27.9 cm). Bruce Weber and Nan Bush Collection, New York. © Bruce Weber.

Baked into that upbringing was a mother who encouraged female education and the study of art (at no less than the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1905 to 1906).

The stage was set for the larger-than-life persona that emerged from that rich soil.

In the fall of 1907, O’Keeffe moved to New York City and attended classes at the Art Students League, studying under the artist-teacher William Merritt Chase. That was the same year Pablo Picasso painted “Les Demoiselle D’Avignon,” widely considered the major proto-Cubist work.

There are no accidents.

Modernism was on the march and O’Keeffe became an insider who happened to work outside any specific art movement – though she was heavily influenced by one of her teachers, Arthur Wesley Dow.

While teaching at Columbia College in South Carolina in 1915, O’Keeffe began to experiment with Dow’s theory of self-exploration and actualization through art. She took natural forms – ferns, clouds, and waves – and began a small series of charcoal drawings that simplified the natural world into expressive, abstracted combinations of shapes and lines. Those were very same images she mailed to the friend who then sent them on to Stieglitz.

Like her contemporary, Arthur Dove, O’Keeffe built her reputation on those abstracted motifs.

“Nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small it takes time – we haven’t time – and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time,” she explained.

O’Keeffe, by Dan Budnik, the last photographer to celebrate the artist. (Image is not in the show).

Now back to the controversy about that work. Was O’Keeffe also, consciously or subconsciously, obsessively recapitulating the female anatomy? No doubt her images were a strong influence on artists of the Feminist movement, including Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro, who saw the intimate female in the florals.

The artist said no, but methinks the lady protested too much – and/or those protests were about something else, about the idea, or a variation on the theme, she threw well – for a girl. Ran well – for a girl. Was O’Keeffe’s objection to anatomical interpretations of her work nothing more than her taking exception to Stieglitz’s contention that art made by a man was naturally, inherently different from art made by a woman? Perhaps in her mind, good or bad, art was art. Gender did not, ahem, enter the picture or have anything to do with the will to form and the resulting work.

A prolific artist, O’Keeffe produced more than 2000 works over a 70-year career. In 1968, Life Magazine produced a 14-page spread about the artist. In 1970, a show of her images traveled the world.

Georgia O’Keeffe, by Dan Budnik. The photographer is in the stable of the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art, but this wonderful image is not in the show.

“Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern” is a homecoming of sorts: the artist’s first solo museum exhibition took place in the same venue, the Brooklyn Museum, in 1927.

The show is a no-miss if you are a fan.

And who isn’t?

For more on the O’Keeffe show, check out Roberta Smith’s in-depth review from the New York Times.

Lee Konitz (born October 13, 1927) is an American composer and alto saxophonist. According to Wikipedia:

He has performed successfully in a wide range of jazz styles, including bebop, cool jazz, and avant-garde jazz. Konitz’s association with the cool jazz movement of the 1940s and 1950s includes participation in Miles Davis‘s Birth of the Cool sessions and his work with pianist Lennie Tristano. He was notable during this era as one of relatively few alto saxophonists to retain a distinctive style when Charlie Parker exerted a massive influence.

Like other students of Tristano, Konitz was noted for improvising long, melodic lines with the rhythmic interest coming from odd accents, or odd note groupings suggestive of the imposition of one time signature over another. Other saxophonists were strongly influenced by Konitz, notably Paul Desmond and Art Pepper.

Like O’Keefe in her universe, in the world of modern jazz, Konitz is an icon.

Lee Konitz at Mezzrow, photo by Clint Viebrock

Following our private tour of the O’Keefe show, we spent a delightful evening in the tiny basement jazz club, Mezzrow, 163 West 10 Street. The show featured Konitz (on alto sax) performing jazz standards with the sensual vocalist Fleurine, Doug Weiss on bass, and Yotam Silberstein in guitar.

We got a crush on them all, sweetie pie.

Fleurine

photo by Clint Viebrock

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.