12 Sep Fall Sunday: Why We Get Outside With Our Students

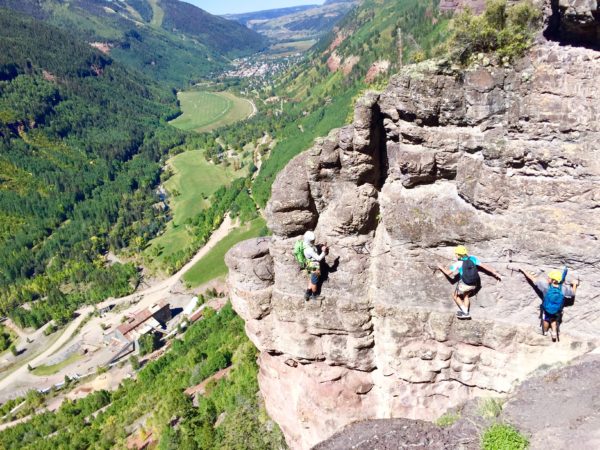

I stand on a gravel switchback below Bridal Veil Falls with the Telluride Mountain School 11th and 12th grade students, fastening my climbing harness. It’s the first Friday of the school year and we’re going to do the Via Ferrata, a protected climbing and hiking route that traverses a narrow cliff band 200 to 400 feet above the valley floor. In Italian, Via Ferrata means “iron way” and this route follows a narrow path supported by iron rungs drilled into the rock and a cable running parallel that climbers can clip into for extra protection.

There is one section on this route called the Main Event, during which, at the route’s highest point, the natural path falls away and climbers must traverse a portion of the cliff, only using the rungs. To step out onto that first rung, with only air below you, takes commitment, trust and confidence — both in yourself and in your group.

And this is why we are doing this—to foster team building and leadership. Throughout the school year, I, along with a team of colleagues and parents have the responsibility, and privilege, of guiding these students in their last two years of high school and through the college counseling process. A journey that even for the most stoic and confident adolescents is scary. The students, although they rarely show it, are vulnerable and exposed in this process. The purpose of today’s exercise is to let them know it’s okay to be uncertain and they can trust each other, but more importantly themselves, when confronting the unknown.

Yet I know, even for the Telluride Mountain School, this is a pretty ballsy thing to do with students the first week of school. But I’m confident in each of them. Each has completed at least four years of Telluride Mountain School’s outdoor education program, one is certified as a Wilderness First Responder, we have two professional guides from Ryder/Walker and Telluride Mountain Guides, my co-teacher has extensive climbing experience, I have extensive outdoor experience, and all adults are either Wilderness First Aid or Wilderness First Responder certified. We also had an “opt out” alternative and each one of these students opted in.

We move onto the route; everyone falls into their own pattern. Most quietly engage in conversations with the person in front of them, two are louder and boisterous, using humor to mask their nerves. We move to the Main Event and give each other space to move across the iron rungs. We hear the chattier boys in front, both known for their big mountain skiing and snowboarding.

“I shouldn’t be this scared,” one says. “There are different types of being scared, and I don’t like this one,” he continues as he moves across. “Noah is crying he is so scared,” he shouts out about his friend and classmate behind him.

We know he is joking, sort of.

I move onto the rungs with a student in front of me who is often quiet in class, but known for his musicianship. He wears black skinny jeans and a colorful tie-dyed shirt. I had convinced him earlier to take off his wallet chain before putting on his harness. I check in with him; he has a huge smile and confidently pauses so I can take a photo.

Behind me is the only female student on this expedition, a serious academic who plays violin in two orchestras. When we discussed the trip earlier in the week, she confessed that she was afraid of heights. I assured her she’d be okay. I check in with her as she moves across the Main Event and she is solid, nervously laughing at the commentating from the skier boys in front.

“This isn’t as bad as I thought it’d be,” she says as she steadily moves across each rung.

There are still exposed spots after the Main Event, but the mood is lighter. The students know the hardest part is behind them and they have more confidence to face the rest of the route. There are a few comments about college, the school year, last year’s short story contest, a class, or teacher, the Olympics – but for the most part, the conversation is trivial.

At the end of the route, we journal and the students discuss how they felt. One student offered that he was willing to do it because he knew had his class with him. Another observed that what seemed really scary at first, wasn’t that bad once you actually started moving through it; you got used to it. Another appreciated the talkative student’s humor. Each chimed in.

I began my journal entry with a line about completing the Via Ferrata with “my” students – a term I often take issue with because students do not belong to any teacher. When I hear this term, I often think of the lines in Kahil Gibran’s poem On Children in his collection The Prophet:

Your children are not your children

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

………..And though they are with you, yet they belong not to you

However, as I spent the day with this new batch of juniors and seniors I realized that “my” doesn’t mean ownership, but instead signifies relationship. In his book The Minds of Boys: Saving Our Sons From Falling Behind in School and Life, author and researcher Michael Gurian stresses the importance of building relationship in classrooms especially to successfully teach boys.

And this is why I am here with these eight 11th and 12th grade students, walking across iron rungs along a rock wall 450 feet above the valley floor below me. To build relationship. I’d be naïve to think that we’ll be able to bring the same energy and camaraderie from the Via into the classroom every day. I know in addition to the successes we’ll have, there will be conflicts throughout the year, student meetings, parent meetings, and disappointments.

But I also know we have this experience as a starting point and that we can move through the obstacles throughout the school year just like we did on the Via – carefully, intentionally, hopefully with a little humor, and most importantly together.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.