15 May Tall Tales: Begley’s Biography of Updike, Reviewed

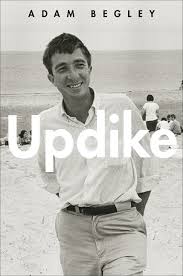

If you marvel at the prose of John Updike, you’ll enjoy the biography by Adam Begley.

I suppose my job is to answer the question for non-believers: Why should I read this?

My answer is this: Begley’s fine portrait helps us see the combination of family forces and innate personality traits that produced one of the finest writers of the 20th Century. Updike is entertaining and deliciously detailed. And, most of all, reading Updike gives us the chance to watch an artist develop and get to work.

Quite literally, work.

John Updike made a commitment as a young teenager and never altered his course. The youthful glint in his eye never faded. He wrote a poem four weeks before his death. With a main character (John Updike) who is intellectually playful and a biographer who so copiously examined the connection between Updike’s “real” life and the many ways he fictionalized that life in the written word, there’s a powerful or interesting idea on each page of this beautifully written book, either from Updike himself or Begley teasing something out.

Perhaps the single most important ingredient in the formative stages of Updike’s career was a mother determined to imprint an only son with ambition and expectations as a writer. But Updike makes it clear that the writer took the idea of limitless possibilities and applied himself like a voracious, insatiable student.

Begley uses close readings of Updike’s short stories and novels (and poetry) for their insights into the life of the man himself. Updike, after all, digested his life for the sake of his art. He may or may not have written with a “callous disregard for his family and other, collateral victims,” but he observed and wrote, and then he observed, and he wrote some more.

Updike spends a fair amount of time on Updike’s youth in Plowville and nearby Shillington, Pennsylvania. It details young John’s interesting and complicated relationship between his mother and father. Mother Linda’s aspiration for a full-fledged writing career were “enough for two,” Begley writes, and young John set his sights high from a very young age.

Updike’s aunt sent the family a subscription to The New Yorker in 1944, when John was 12, and the young writer, really, never looked back. He loved the cartoons and for many years developed talent as an illustrator and cartoonist but adjusted course after a successful and inspiring run at Harvard University (full scholarship) and at Oxford University (Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art). Along the way, he learned to love the Romantic poets and Shakespeare—and recognized his own talent for telling a story on the page.

Updike shows that the writer’s ambition drove everything. Being a staff writer at The New Yorker, at a tender age, wasn’t enough. Though his relationship with the publication lasted all his life, he moved away and set his sights on full-length fiction, fueled perhaps by a fresh admiration for Marcel Proust and the power of prose. “It was a revelation to me that words could entwine and curl so, yet keep a live crispness and the breath of utterance,” Updike wrote on reading Proust. “I was dazzled by the witty similes … that wove art and nature into a single luminous fabric. This was not ‘better’ writing, it was writing with a whole new nervous system.”

Begley makes it clear that Updike had taken a fairly significant risk in leaving the well-cushioned life of a New Yorker staff writer. There were no guarantees. There were setbacks. But all obstacles withered in the face of Updike’s flying pencil.

Over time, Updike would develop three principal leading men to live his life on the page—Richard Maple, Henry Bech and Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, the star of the four novels and one final novella. Religion played a key role. So did golf. And so did sex. And sometimes (A Month of Sundays), all three.

Couples launched him to the level of public figure—a novel about the lives of well-off suburbanites in fictional Tarbox, Massachusetts were busy balancing their religious upbringing with the new freedoms of the mid-1960’s. “Curiously muffled,” Begley writes, “the satiric element in Couples lies buried under two layers: Updike’s exuberant prose, which wraps in baroque splendor whatever it touches, and the mass of sociological detail provided about Tarbox and its inhabitants.”

Begley’s deep dive into novels is powerful—particularly the Rabbit tetralogy and the three novels inspired by The Scarlet Letter—A Month of Sundays, S., and Roger’s Version. Begley gives strong play to Updike’s short stories, poetry and literary criticism, too. So Updike is part-biography and part-literary analysis. Reading Updike will make you want to pluck a title off the shelf and start reading his works all over again, this time armed with more awareness and insights about the man behind the words.

In Updike’s own memoir Self-Conciousness, Updike said he approached the work with “scientific dispassion and curiosity.” Begley accomplishes the same—and simultaneously makes a convincing case that Updike, while hardly perfect, belongs with the best.

For my interview with Adam Begley, go here.

Editor’s note: Telluride Inside… and Out’s monthly (more or less) column, Tall Tales, is so named because contributor Mark Stevens is one long drink of water. He is also long on talent. Mark was raised in Massachusetts. He’s been a Coloradoan since 1980. He’s worked as a print reporter, national news television producer, and school district communicator. He’s now working in the new economy and listed under “s” for self-employed. Mark has published two Colorado-based mysteries, “Antler Dust” (2007) and “Buried by the Roan” (2011). Midnight Ink will publish the third book, “Trapline,” in the fall of 2014 and is under contract for a fourth book in the series, too. For more about Mark, check out his website.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.