18 May Mountainfilm: Gallery Walk 2014 Features Uelsmann & Taylor

Work now on display at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art, which has represented the duo’s images for years

Fact: Jerry Uelsmann and Maggie Taylor are photography world royalty. Over the years, the husband and wife team has produced a body of work that conveys feelings of unreality, infusing the ordinary with a sense of magic and mystery. By means of exacting realistic techniques, they have each managed to make plausible and compelling improbable, dreamlike and fantastic visions, which tend to throw viewers more than little off balance. Widely collected image-makers, their work hangs in major museums around the world, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum and the Royal Photographic Society and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Hot on the heels of the Moving Mountains Symposium on “Wilderness,” Mountainfilm in Telluride officially kicks off with Gallery Walk, a round of receptions featuring major artists at galleries around town. The work – paintings, drawings, photography, installations – is mesmerizing and inspiring; the drinks and hors d’oeuvres are free.

Uelsmann’s and Taylor’s digital photography hangs in the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art over Memorial Weekend, Friday, May 23 – Monday, May 26. Compilations of their work have just come out.

Uelsmann’s book, “Uelsmann Untitled,” released in March, is a collection of over 200 of his images spanning 1959 – 2013.

Taylor’s book, “No Ordinary Days,” surveys her work from 1998 – 2012.

“In her digital photomontages Maggie Taylor opens for us multitude of doors into a seductive, richly nuanced dream world. However unlike many who explore the cross-breeding of imagery that digital systems enable, Taylor creates a microcosm with deep ties to the past. Not just the immediate past that becomes an inevitable aspect of each photographic exposure we make, but the distant past of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,” said A.D. Coleman in an essay about the book.

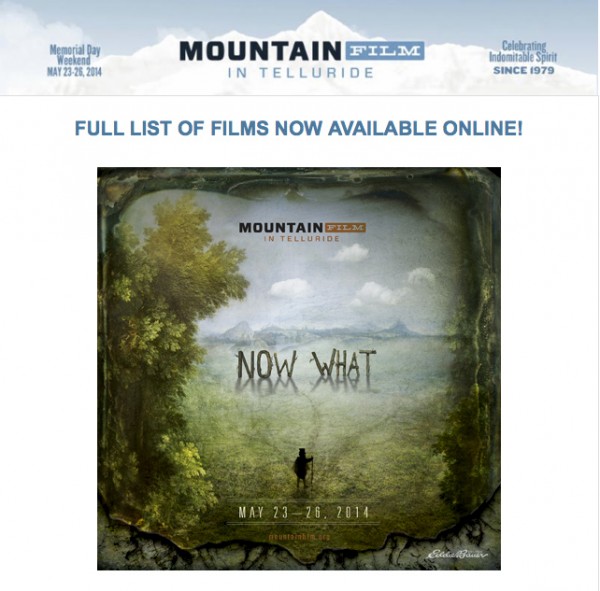

And Maggie Taylor is the poster artist for Mountainfilm 2014.

For an inside look at how Uelsmann and Taylor work, click here.

For a preview of their Mountainfilm show, watch Clint Viebrock’s video.

More about Taylor:

Though she is all about digital and her husband works in the darkroom, Maggie Taylor is also technically brilliant and unapologetically enigmatic.

Taylor grew up in the 1960s/1970s, when social commentary was the name of game in the work of Pop artists such as Andy Warhol. Taylor’s images, however, are less social commentary and more personal statements, often, though not always with a feminist cast.

In her studio, Taylor has drawers and shelves filled with all kinds of objects and pieces of text. The artist tends to choreograph the detritus of her life indoors before taking the items outside into her yard to photograph them with an old view camera in natural light. An avid gardener, Taylor also find inspiration as well as actual material to scan when outside.

“I often work spontaneously, incorporating things I find in my garden on a particular day. My intentions when I am creating are generally nondescript, but the end-result must be visually appealing. I want my viewer to experience a convergence of factual memory and fictional daydreams, which is similar to my own internal dialog when creating the work.”

How does Taylor create her squeaky clean images?

“Often when people think about using the computer to make art, they mistakenly think that it is an easy solution or a very quick process. In my experience, using the computer is slower than working with a camera and film. I go back again and again to the images and refine and improve them. I only make about 10 to 15 images a year and I can be working on one image for a few weeks or even a month. My images can easily be over 200 layers in the end. That said, for me, both computer and camera are great ways to document as well as transform reality.”

Uelsmann on Taylor:

“Maggie is an expert in Photoshop and uses the program to build wonderfully cryptic images, which I see as both playful and scary – and I think we are on similar wavelengths. I think that the computer is a valid tool for making art. Anything works which allows an artist to alter the world in visually interesting ways.”

Taylor holds a B.A. in philosophy from Yale and an M.F.A. in photography from the University of Florida.

More About Uelsmann:

Jerry Uelsmann is the acknowledged master innovator of photomontage. He began producing his dramatic photomontages in the 1960s, black-and-white images that are not at all black and white, rather unsettling alternatives to naturalism. These surrealistic, hyper, super or anti realities – call them what you like, the labels are just variations on a theme – amount to a psychic topography developed from things that happened at the fringes of Uelsmann’s consciousness.

Clues to the meaning of the work, however, could be derived from artist’s symbolic vocabulary, which has remained surprisingly consistent over the years: nature and culture cross boundaries when interiors meld with exterior landscapes. Figures levitate and fly as in dreams, free of gravity. Monumental hands, a classic element in Surrealist photography of the 1920s and 1930s, appear everywhere. Other bizarre, even grotesque Surrealist motifs include disembodied human parts, humans merging with trees, rocks and water, animal, vegetable and mineral blending and intertwining, the stuff of the shadow world. Universal archetypes such as house, tree, sky and water, are all re-contextualized, forcing us to confront them like children: with wonder and for the first time.

Confronted with these images, viewers are forced into an internal dialogue between what they know intellectually about photography – the medium depicts things as they are, right? – and what they are being made to confront. The inventive consciousness of Uelsmann’s viewers then becomes another element in the picture frame. Describing the work, scholars have drawn analogies to lyrical poetry, because the artist’s elusive work clearly falls into the narrative, as well as the visual tradition.

Content notwithstanding, composition in an Uelsmann is also a subject worth exploring. Uelsmann is considered a virtuoso in the the darkroom, where he pioneered and is continually perfecting new bravura developing techniques. For starters, on three or more of the eight enlargers in his darkroom, the artist combines parts of all of two or more negatives, which he burns and dodges (exposes sections to more or less light) to make his final, seamless black-and-white prints.

Uelsmann refers to his unique way of working as “in-process discovery” or “post visualization,” an idea that turns Ansel Adams’s notion of pre-visualization on its head. Pre-visualization demands that a photographer see in his mind what he wants to create at the moment of exposure. Uelsmann’s theory allows photographers to rethink an image at any point in the photographic process, to imagine “what if.”

Jerry Uelsmann was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1934. In the early 1950s, he attended Rochester Institute of Technology, where Minor White was among his teachers and a major influence. White is widely quoted as saying the goal of a serious photographer – read fine art, not point and shoot – was to get from the tangible, what things are, to the intangible, what else they are, to create visual metaphors.

After earning a masters degree at Indiana University, Uelsmann began teaching at the University of Florida in Gainesville, where he and Taylor still make their home.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.