20 Dec Wade Davis, Sacred Headwaters, a Victory – For Now

The Stikine Valley in British Columbia is sacred to the First Nations people, the Tahltan. The region encompasses one of the largest predator-prey ecosystems in North America. Rich in wildlife – caribou, stone sheep, moose, mountain goats, grizzlies and wolves – and mountain majesty, the Sacred Headwaters, about 200 miles south of Watson Lake, Yukon, and 150 miles east of Juneau, Alaska, is also – and here’s the good news and the bad news – rich in energy and minerals. The Stikine until very recently was threatened by energy development.

The Stikine Valley in British Columbia is sacred to the First Nations people, the Tahltan. The region encompasses one of the largest predator-prey ecosystems in North America. Rich in wildlife – caribou, stone sheep, moose, mountain goats, grizzlies and wolves – and mountain majesty, the Sacred Headwaters, about 200 miles south of Watson Lake, Yukon, and 150 miles east of Juneau, Alaska, is also – and here’s the good news and the bad news – rich in energy and minerals. The Stikine until very recently was threatened by energy development.

Telluride became aware of the David & Goliath story several years ago, thanks to Mountainfilm regular, Wade Davis.

Davis is explorer-in-Residence at the National Geographic Society, ethnobotanist, poet, photographer, and eco-activist. He is also the author of numerous books, including “One River” and “The Serpent and the Rainbow.” Davis has lived and worked in the Stikine as a park ranger, guide, and anthropologist since 1978. He and his wife, Gail Percy, own Wolf Creek Lodge, the closest private holding to both the Sacred Headwaters – and the proposed site of the Red Chris mine.

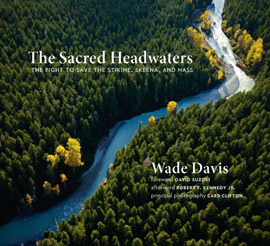

In part to raise funds to fight the mining, Davis wrote the text for a book entitled “The Sacred Headwaters: The Fight to Save the Stikine, Skeeba, and Nass,” illustrated by a collection of photographs by the International League of Conservation Photographers and by other professionals who have worked here, including Sarah Leen of the National Geographic. Davis’ compelling words described the region’s beauty, the threats to it, and the response of the inhabitants. The inescapable message: no amount of methane gas can compensate for the sacrifice of a place that could be the Sacred Headwaters for all the peoples of the world.

Davis’ book was published in November 2011. This hopeful story about how native and nonnative came together to fight the drilling and, at least for now, Shell is not doing its thing. Davis is quoted at the end of the article by Ted Alvarez that appeared in Grist (12/18).

I’m helicoptering over a thousand-mile mess of dirt-dusted glaciers, spongy tundra, and bristling forest in the far north of British Columbia. My gut wobbles as we drop past mountain ridges toward our destination: a soupy, pea-green bog dotted with a handful of black ponds. Fed by whitewater trickles draining the peaks around us, it’s a sucking, primordial muck reminiscent of an antiquated dinosaur mural, or a day-glo panel from Swamp Thing’s origin issue. And sure enough, it’s the birthplace of something big, ancient, and slippery: the Skeena, Nass, and Stikine — three of the largest salmon rivers on the West Coast, all born here or near here in the Sacred Headwaters.

But the Sacred Headwaters doesn’t owe its growing fame to the chinook, coho, and silver salmon races that have been flapping up these rivers since before the Bering Strait opened to pedestrians. For that, we ultimately must thank what lies buried directly 2,000 feet below: 8 trillion cubic feet of natural gas trapped inside vast beds of coal.

Even distant spectators of climate change news know we hear almost all bummer tunes. Between the Chinese-finger-trap gridlock of domestic politics and moribund international summits always ending with grim predictions and toothless resolutions, avoiding an apocalyptic New Normal seems impossible. As an increasingly fatigued spectator, I look for any reason to emerge from under my Linus cloud. That’s why I jumped when I heard whispers about a remote community in Northern B.C. — First Nations tribe elders, hunters, loggers, sportsmen, skiers, tar-sands workers, environmental NGOs, parents — who all banded together to dissuade no less than Shell Oil from digging up all that carbon. It seemed like a rare clean win, a satisfying victory in an eight-year fight that kept carbon in the ground and high-fived fish over fossil fuels.

Shocker: The reality is much, much more complicated than that…

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.