27 Nov Poets’ Corner: Feela on Turkeys & Happy Thanksgiving All

“What we’re really talking about is a wonderful day set aside on the fourth Thursday of November when no one diets. I mean, why else would they call it Thanksgiving?” Erma Bombeck

In a letter to his daughter, Ben Franklin proposed the turkey for the official bird of the United States. (See below.) But Charles Dickens could be one reason the turkey is the mainstay of the Thanksgiving table. Published in 1843, “A Christmas Carol,” with its classic menu of turkey with gravy, stuffing and plum pudding, convinced many Americans, avid fans of the author, to feature the bird earlier in the holiday season. Or perhaps it is all due to Sarah Josepha Hale, the influential editor of the magazine “Godey’s Lady’s Book.” In her 1827 novel “Northwood,” Hale described the Thanksgiving feast. She began with turkey set in a “lordly station,” flanked with sirloin of beef, ducks, geese and and a leg of pork. (Hale also added an array of veggies to her table and a chicken pie.)

Dickens or Hale, turkeys were a righteous choice: birds born in the spring would spend about seven months eating insects and worms on the farm, growing to about 10 pounds by Thanksgiving. They were cheaper than geese, which were also more difficult to raise, and cheaper by the pound than chickens. And cost was a factor because cooks were not only preparing one meal. Thanksgiving was the time to bake meat and other pies that could last the winter. Today, 46 million turkeys are gobbled up each Thanksgiving (22 million at Christmas) and last year alone, the average American consumed 16 pounds of the big bird.

But all this happy turkey talk puts Telluride Inside… and Out contributor David Feela to sleep. (And that has nothing to do with tryptophan.) David favors Big Bird.

Read on for details….

AND HAPPY THANKSGIVING. (Try not to throttle your mother-in-law.)

The American Bird

by David Feela

A wild turkey crossed my path last year while I hiked along Petroglyph Trail, a recreational sidebar within the greater Mesa Verde National Park, on — of all days — Thanksgiving Day. It posed in the open for an instant and tried to stare me down before calmly moving off — an alert, fully plumed and magnificent specimen of a game bird. I felt as if it had stopped to emphasize the difference between itself and the pale, plucked, over-greased variety of America we stuff into so many tiny 350 degree tanning booths on the fourth Thursday of each November.

In all fairness to the wild bird, let me mention how Benjamin Franklin confided to his daughter in a 1784 letter that the turkey would have been a better choice for the Great Seal of this country than the Bald Eagle, which had been officially adopted by Congress in 1782 as our national bird. The eagle, he suggested, was a coward, a bird of inferior moral character, a lazy opportunist that scavenged and did not garner its living honestly.

I doubt if Franklin ever weighed the merits of each bird when it came to providing for the Thanksgiving table.

Perhaps I should have been at home with family like so much of America, crowded into one room, surrounded by relatives, watching at least one football game on at least one television, eating a second piece of pumpkin pie, sipping another beer, instead of hiking this silent path. I’ll probably get in trouble for saying this, but holidays often prompt an irresistible anti-social feeling inside me, an urge to get off on my own, to participate in no gathering, to share no experiences, to converse almost exclusively with the rocks and trees.

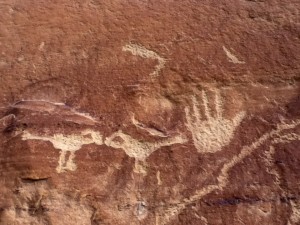

And here I’d arrived at a spot where five hundred years prior to Franklin’s familial letter, some anonymous hands with pointy rock tools pecked an array of images into this southwestern Colorado cliff wall, and several of the petroglyphs depicted birds. Maybe they are turkeys, it’s hard to tell, but they stand, silently posed beside the outline of a flattened, open human hand — the same figure all first graders are taught to draw in class before the fall holiday by tracing a line around the peninsulas of their tiny fingers. I counted exactly two birds beside that single handprint on the rock wall, and it struck me as a shoe-in for the adage, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

Eventually I continued along the trail, returning to the Spruce Tree museum, where I paused at that great vantage point overlooking those prehistoric condo cliff dwellings below. The path was still deserted.

Turkeys, one; Tourists, zero.

Over 2 million years ago, wild turkeys existed, based on the scientific dating of fossil remains, and it’s even possible the Aztecs had domesticated a variety of the bird. The turkey was here in North America when the Puritans landed, and still here when Benjamin Franklin flew his kite.

I try to imagine the sheer absurdity of proposals being swatted back and forth by our early politicians that finally concluded in the Great Seal decision, which might have threatened to become our first legislative gridlock, and we should be thankful an albatross didn’t end up as the emblem for our democracy.

I remember only two years ago when politicians used Big Bird as a battle flag for their campaigns. You know the bird, the only pure American symbol of kindness, stature, and diplomacy — not red, not blue, but yellow. Maybe it’s about time for a new symbol. Maybe Big Bird ought to be nominated to appear on the Great Seal of this country, not predator or prey, not rich or poor, not Republican or Democrat, but an 8 foot pillar of unruffled feathers that stands, literally, for rising above it all.

Art Goodtimes

Posted at 17:03h, 29 Novembera brilliant and illuminating column from one of the southwest’s best writers. david feela is a regional treasure. thanks for publishing this TIO…