24 Sep TIO NYC: Happenings at the Museum of Modern Art

Magritte (through January 12, 2014):

Magritte (through January 12, 2014):

What you see is not necessarily what you get.

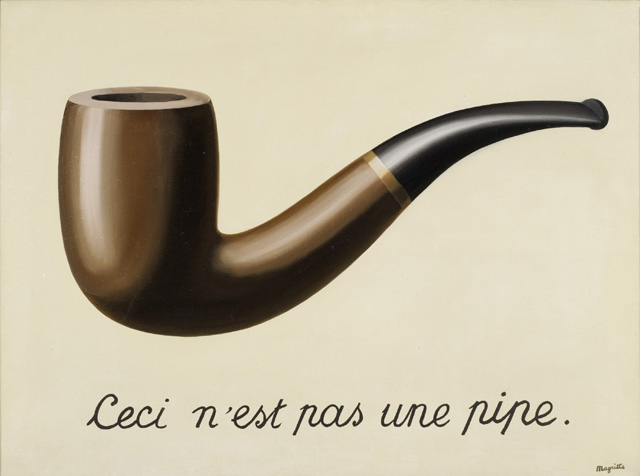

What you see is a pipe. But the label says: “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” “This is not a pipe.”

And despite appearance, the object is not a pipe. Why? Because you can’t smoke it, declared Rene Magritte, (1898 – 1967), an artist who thumbed his nose at what seemed obvious. It is in fact a representation of a pipe. It is, in other words, a painting. His painting. One of the most iconic of the Surrealist movement and a work which sums up “ism’s” raison d’être.

Surrealism officially proclaimed its existence with the publication of a Manifesto in 1924. The movement owes its name to French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who in 1917 uses the term “sur-réaliste” to describe a form of expression that surpasses realism. Inspired by Freud’s then recently published insights into the unconscious, Surrealists like Magritte aimed to subordinate the rational mind to instinct. Led by the poet André Breton, adherents of the movement proposed an alternative agenda for the transformation of society. In Surrealism’s later years, Breton described the goal in an interview:

“Completely against the tide, in a violent reaction against the impoverishment and sterility of thought processes that resulted from centuries of rationalism, we turned toward the marvelous and advocated it unconditionally.”

Eighty works – paintings, collages and objects, plus photographs, periodicals and early commercial work – by Magritte are now on display at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in a show entitled “Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary.”

MOMA’s Magritte show, co-organized by The Museum of Modern Art, The Menil Collection, Houston, and The Art Institute of Chicago, is the first to focus exclusively on the breakthrough Surrealist years of the creator of some of the 20th century’s most extraordinary signature images.

Beginning in 1926, when Magritte first aimed to create paintings that would, in his words, “challenge the real world,” and concluding in 1938—a historically and biographically significant moment just prior to the outbreak of World War II—the exhibition traces central strategies and themes from the most inventive and experimental period in the artist’s prolific career. Displacement, transformation, metamorphosis, the “misnaming” of objects, and the representation of visions seen in half-waking states are among Magritte’s innovative image-making tactics during these essential years.

For a full and very good review, go to this article by New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman.

Dorothea Rockburne: “Drawings Which Makes Itself” (through January 20, 2014)

Dorothea Rockburne: “Drawings Which Makes Itself” (through January 20, 2014)

Magritte was a familiar name, whose familiar work became more interesting in the context of this sweeping overview of the artist’s richest period. Dorothea Rockburne, thanks to a friend, was a revelation. Her works fashioned from paper and other mundane products such as crude oil, like many Surrealist works, transforms the quotidian – but without the need to shock for shock’s sake.

Rockburne, born 1932 in Montreal, Canada, is an abstract painter who drew inspiration primarily from a deep interest in mathematics and astronomy.

In 1950, the artist moved to the United States to attend Black Mountain College, where she studied with mathematician Max Dehn. The man became a lifelong influence on her work. In addition to Dehn, she studied with Franz Kline, Philip Guston, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham. She also met fellow student Robert Rauschenberg.

In 1955, Rockburne moved to New York City where she met many of the leading artists and poets of the time.

“Drawing Which Makes Itself asks this question: “How could drawing be of itself and not about something else?”

Having first asked the question in 1973, Rockburne went on to answer it in visually compelling and intellectually provocative ways that tested the bounds of traditional drawing practice. The current exhibition at MOMA examines the artist’s groundbreaking project, “Drawing Which Makes Itself,” of 1972–73, while highlighting ideas she has pursued throughout her career.

Rockburne has said that paper has “terrific importance” for her:

“I came to realize that a piece of paper is a metaphysical object. You write on it, you draw on it, you fold it.”

She is interested in paper not just as the ground for a drawing, but also as an active material, its inherent qualities determining the form of the artwork, a fact made clear in works such as Scalar (1971), with its planes of chipboard and paper stained with crude oil and in the carbon-paper drawings installed on both the wall and the floor. (The series is on view at MOMA for the first time in 40 years.)

Rockburne ‘s Golden Section Paintings (first exhibited in 1974 at MOMA and thanks in large part to Dehn’s teachings), as well as several series of works on paper that followed, refer to a mathematical ratio used by artists and architects since antiquity to produce shapes of harmonious proportions. Rockburne’s work of later decades, including recent watercolors on view at the exhibition’s entrance, continues her exploration of these principles in nature and specifically in the motion of planets.

For further insights, watch this video.

American Modern: Hopper to O’Keeffe (through January 26, 2014)

This show pairs nicely with the Hopper show at the Whitney. (See related post.)

Drawn from MOMA’s collection, “American Modern” takes a fresh look at the Museum’s holdings of American art made between 1915 and 1950 and considers the cultural preoccupations of a rapidly changing American society in the first half of the 20th century.

Continue reading here for more….

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.