19 Jan HONORING MARTIN LUTHER KING

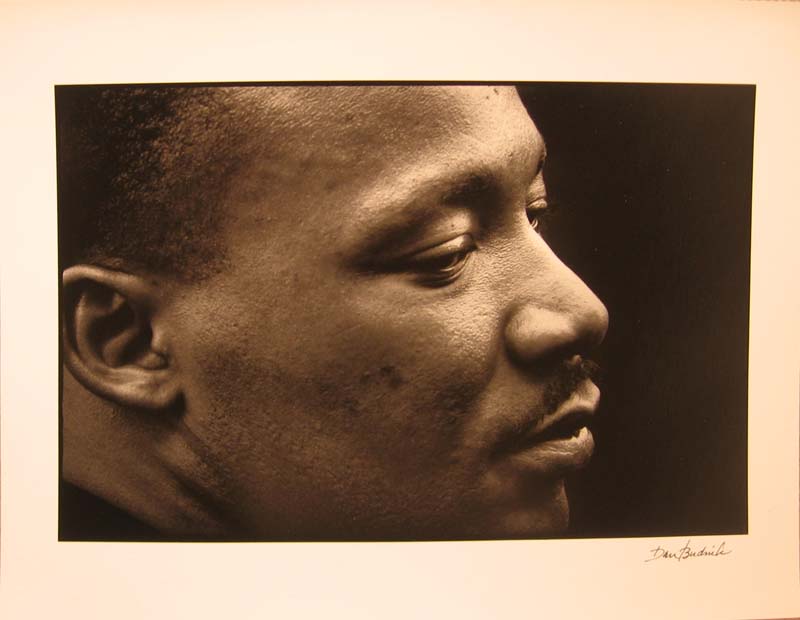

MARTIN LUTHER KING, BY DAN BUDNIK

Martin Luther King, Jr. made history. Dan Budnik was an eyewitness and chronicler. Many of Budnik’s images were never published in the mainstream media. Others, such as one his portraits of King delivering his “I Have A Dream” speech at the Lincoln memorial, became iconic.

A collection of Budnik’s rare prints capturing King in action from 1958 – 1965, some now on display- is available at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art.

According to Gallery director Baebel Hacke, the show provides “a rare great opportunity for young people in this community to ‘witness’ events through the eyes of award-winning photographer Dan Budnik.”

The deep history between King and Budnik begins with King’s earliest protest of Montgomery’s segregated bus system in 1955. In 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Montgomery to provide equal, integrated seating on public vehicles.

In 1960, black college students across the South began sitting at lunch counters and entering buildings traditionally off limits for black Americans.

In 1963, King and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) associates launched massive demonstrations to protest racial discrimination in Birmingham, Alabama, one of the South’s most segregated cities. The police responded with dogs and fire hoses, which they used on peaceful protesters, even children. In response to a national outcry, JFK proposed a wide-ranging civil rights bill to Congress.

In support of that bill, King and other civil rites leaders organized a massive march on Washington. On August 28, 1963 over 200,000 Americans, including many whites, gathered at the Lincoln Memorial. The high point of the rally was King’s stirring “I Have A Dream” speech, which defined the moral basis of the civil rights movement.

Budnik was there, right behind The Man.

In 1964, the African American baptist minister won the Nobel Peace Prize for leading nonviolent civil rights demonstrations. His actions were based on the principle of civil disobedience, the strategy of turning the other check practiced for centuries by great leaders from Jesus Christ to Saint Thomas Aquinas and Ghandi.

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King, by Dan Budnik

In 1965, King helped organize more protests in Selma, Alabama. This time his targets were white officials wanting to deny black citizens the chance to register and vote. Several hundred protesters attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital, but police officers used tear gas and clubs to break up the crowd. The bloody attack, known in the history books as “Bloody Sunday,” was broadcast nationally and shocked the rest of the nation, which witnessed the brutality on TV. Two days later, King announced a second march, but after a group prayer at the site of Sunday’s confrontation, he had marchers turn back to Brown Chapel in Selma.

Again Budnik was in the thick of the action.

Budnik’s images remain among the most famous of the period, noteworthy because he was not drawn to scenes of violence, but to the spaces in between snarling police dogs, attacks at lunch counters, and angry whites. Even his images of flaming racists are more comical than frightening.

In 1998, Budnik became the recipient of American Society of Media Photographers, Inc.’s Honor Roll. The honor is given to an ASMP member who has set a standard for photography, ethics, professionalism, behavior and demeanor in the profession. The recipient is someone who could be emulated and could serve as a role model. Past recipients include Man Ray, Dorothea Lange, Ernst Haas, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks, Ansel Adams and Arnold Newman.

Budnik’s work is included in the permanent collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Albright-Knox Museum, Buffalo, NY and Fine Arts Museum of Houston, TX.

For further information go here or call 970-728- 3300.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.