04 May EARTH MATTERS: UNDERWATER ART HELPS SAVE REEFS

Academic and professional conferences, in my experience, produce very few “WOW” moments. So when I came down to St. Petersburg, Florida, for the Coastal Counties Summit this week, I expected to hear some good talks, make a few contacts and grab some time to write my regular column for Telluride Inside… and Out. I had planned to tackle “revolving door” and “regulatory capture” at the federal agencies, but got sidetracked. Instead I want to introduce our readers to a place I have never been, but discovered this week at the conference: MUSA.

Academic and professional conferences, in my experience, produce very few “WOW” moments. So when I came down to St. Petersburg, Florida, for the Coastal Counties Summit this week, I expected to hear some good talks, make a few contacts and grab some time to write my regular column for Telluride Inside… and Out. I had planned to tackle “revolving door” and “regulatory capture” at the federal agencies, but got sidetracked. Instead I want to introduce our readers to a place I have never been, but discovered this week at the conference: MUSA.

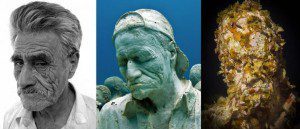

MUSA is the acronym for the Museo Subacuático de Arte in Cancun, an underwater sculpture museum that was the brainchild of two men, one a scientist and natural resource manager, the other a business owner and amateur ceramicist. With the work of a third man, the Guyanese-English underwater sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor, the pair imagined, designed, and implemented a project that helps protect reefs and creates a beautiful and evolving art happening in an unexpected setting.

MUSA is the acronym for the Museo Subacuático de Arte in Cancun, an underwater sculpture museum that was the brainchild of two men, one a scientist and natural resource manager, the other a business owner and amateur ceramicist. With the work of a third man, the Guyanese-English underwater sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor, the pair imagined, designed, and implemented a project that helps protect reefs and creates a beautiful and evolving art happening in an unexpected setting.

Cancun is one of the busiest tourist destinations on earth. It is also home to a National Marine Park, the Parque Nacional Isla Mujeres-Cancún-Nizuc, declared a protected area in 1996. While the park designation has provided some protections to the coral reefs in the area, there are still a number of stressors on these vital ecosystems. Natural disasters, like Hurricane Ivan, have taken their toll on the corals, as has heavy tourism traffic. (The park gets over 750,000 visitors annually, including nearly 200,000 scuba divers per year.)

Jaime González Cano, park director and a presenter at the conference, wanted to find a way to solve two distinct but related problems. First, he wanted to help restore damaged habitat. Second, he wanted a way to redirect tourists away from some of the most sensitive reef areas. He explored shipwreck visits as an alternative to reef snorkeling and scuba, as well as reef balls with replanted coral. Reef balls, though, are not particularly visually attractive – they look kind of like giant unexploded ordnance shot through with holes – and therefore do not do a great job of pulling visitors away from natural reefs.

Jaime González Cano, park director and a presenter at the conference, wanted to find a way to solve two distinct but related problems. First, he wanted to help restore damaged habitat. Second, he wanted a way to redirect tourists away from some of the most sensitive reef areas. He explored shipwreck visits as an alternative to reef snorkeling and scuba, as well as reef balls with replanted coral. Reef balls, though, are not particularly visually attractive – they look kind of like giant unexploded ordnance shot through with holes – and therefore do not do a great job of pulling visitors away from natural reefs.

With one of the biggest tour operators in the area, Roberto Diaz Abraham, a co-presenter at the conference, Cano came up with a novel concept: attract divers with something that is actually attractive, something that can also serve as a coral reef nursery and fish habitat: a sculpture garden that is also a coral garden. MUSA.

Not many sculptors are trained in underwater sculpture, which requires the use of materials sculptors do not traditionally work with, for one, a stronger concrete that is less susceptible to breaking down. Cano and Abraham had seen photos of Taylor’s work in Guyana and thought, “There’s our man.” The project started with just three sculptures, but now includes over 400. Taylor’s pieces were joined by the work of five other artists, including Diaz Abraham, who created a ceramic sculpture that he then turned into a mold for a concrete underwater sculpture.

Not many sculptors are trained in underwater sculpture, which requires the use of materials sculptors do not traditionally work with, for one, a stronger concrete that is less susceptible to breaking down. Cano and Abraham had seen photos of Taylor’s work in Guyana and thought, “There’s our man.” The project started with just three sculptures, but now includes over 400. Taylor’s pieces were joined by the work of five other artists, including Diaz Abraham, who created a ceramic sculpture that he then turned into a mold for a concrete underwater sculpture.

Many of Taylor’s sculptures draw from community members and a number incorporate environmental issues. For example, “Inheritance” shows a young boy looking at trash, but it is optimistic, too, because trash in this context becomes a host for colorful coral. Each sculpture weighs about four tons, with some tipping the scale at eight tons. (One was too heavy for the boat and needed balloon-like air-bag attachments to keep it from sinking too soon as it was being transported to the exhibit.)

The formal inauguration of the first gallery was November of 2010. The vision for the park is to keep adding “exhibit rooms” and new sculptors, and maybe even new MUSA locations worldwide. To date, the total amount invested in the project through public-private partnerships is about $3.6 million.

MUSA seems to be succeeding already on a number of fronts. Estimates show that about 20,000 visitors are staying out of the reefs and spending time in the museum instead. Planted coral and other sea plants are growing on the sculptures. Fish are returning to an area that was essentially an underwater desert before the innovative project took hold. (Were you to look at some of the sea floor around the sculptures, you would see that it is essentially barren.) Visitor centers are helping tourists understand the ecological purpose of the museum and also tell the story of how the art was created.

Both González Cano and Diaz Abraham were animated when talking about the project, not your typical way of implementing a management plan for a national park. They particularly stressed the importance of working with the local governments and community members, saying, “As long as you work with the community and the authorities, you can be successful.”

Both González Cano and Diaz Abraham were animated when talking about the project, not your typical way of implementing a management plan for a national park. They particularly stressed the importance of working with the local governments and community members, saying, “As long as you work with the community and the authorities, you can be successful.”

And a little creativity – make that a lot – goes a long way.

The museum website (in Spanish) is available at http://www.musacancun.com/informacion.html.

All photos are from Jason DeCaires Taylor’s website at http://www.underwatersculpture.com/index.asp, which also provides an excellent English-language description of the project.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.