05 Sep Telluride Film Fest 2017: Another Monster Weekend

Asked if he enjoys the process of making films, the sardonic director Guillermo del Toro replied with a wink: “Making movies is like eating a shit sandwich. You get more or less bread, but you always get shit in between.” Immediately, somewhat paradoxically, adding: “Love is divine. And I love cinema. For me, love is completely indistinguishable from cinema.”

Many festival pet their celebrities.

Not Telluride.

That’s because the Telluride Film Fest is not a booty call or a swag grab or a giant photo op. Here you find no big-budget pap, no paparazzi either.

The Telluride Film Fest is red meat for cinephiles only – stars, writers, directors, producers, plain folks who like watching – people like del Toro in love with the art, not the business, of filmmaking. Every year – and 2017 is no exception – the directors, currently Julie Huntsinger and co-founder Tom Luddy – manage to pick movies that remind us why we are willing to hole up in dark theaters when the sun is shining outside. Why we are willing to out ourselves as voyeurs. Why we love movies in the first place: to be mesmerized, enthralled.

There is no ‘Downsizing” that.

“The Shape of Water”:

Del Toro was overcome with, err, a wave of that love when he made “The Shape of Water,” one of the defining, shining movies of the 44th annual Telluride Film Festival. This magical ribbon of dreams (Orson Welles) hits that elusive sweet spot dead center, the place where intelligent storytelling, superior filmmaking and escapist entertainment fuse into something resembling a classic – and, in this case, the writer-director-producer’s best work since his 2006 “Pan’s Labyrinth.” A sure Oscar contender in a number of categories including Best Actress for its lead, the peerless Sally Hawkins. (Witness “Arrival” lest you doubt a hyper-real fantasy ever gets a nod.)

In addition to being a B-horror flick, a soaring musical, a Cold War noir, and romantic comedy rolled into one irresistible package, “The Shape of Water” is also a dark portrait of machismo and its discontents and a wicked send-up of many of the resurgent values that have now and again ruled the roost in America since, well, our country was founded to fight (religious) prejudice from across the pond. And it is one of a number of important films that deal directly or indirectly with the existential crises our world and the world writ large face today.

But in the end, the film is not unrelentingly dark. In fact, quite the opposite: Del Toro uses his megaphone to shout about love. And not just love between a couple, but love in a number of contexts: father and son, mother and daughter, love between friends, the love that dares not speak its name, and the love that spontaneously arises between perfect strangers when Cupid’s arrow hits its mark.

Quoting the self-professed failed Catholic, but transcendent filmmaker once again: “If it is a sin, I am in.”

Just after WWII right through the Camelot years of the early 1960s, was a fine time indeed to be an American – that is, according to del Toro, if you were WASP and hetero. There was a chicken in every pot and a Ken for every Barbie. (A trope made real in the film through the person of the real villain, an OCD fed played to chilling – and comedic – perfection by Michael Shannon.)

But it had to be Ken: showing up at the local PTA with your beloved fish-man on your arm would have been considered more than bad form.

It would have been a sin.

A sin del Toro (thank heaven) embraced and turned into his latest and perhaps greatest other-worldly story to date.

The sensuous, beguilingly beautiful fairy tale for adults has its origins in the writer-director’s childhood when del Toro remembers dreaming he could breathe underwater. It is also a nod to one of the horror films he loved as a young man: “Creature from the Black Lagoon.” As in “The Shape of Water,” the leading (Gill) Man of the title is a strange, prehistoric beast who lurks in the depths of the Amazonian jungle and first swam into a theater near you in 1954. “Creature” is a story of unrequited love and pointless killing – travesties the diehard romantic del Toro was determined to correct in his story.

Pictured: Julie Adams and the Gill Man in Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1954.

Del Toro set “The Shape of Water” against the backdrop of Cold War America circa 1962, when the favorite “Other” was the Russians. Yes, what goes around… That was one year before the Kennedy assassination, when America was turned upside-down. Good bye Camelot. (Forever?)

His leading lady, Sally Hawkins, is a decidedly un-Hollywood heroine, a jolie laide, but also a chameleon who, in this film, appears to be lit from inside. Hawkins’ emotional and physical elasticity is breath-taking. Her soaring performance is inspired by a mixed bag of Buster Keaton, Charlie Chapin, Stan Laurel and Audrey Hepburn.

We first meet Hawkins’ timid, lonely orphan, also a mute, through her best friend Giles, Richard Jenkins as everyone’s eccentric uncle. Giles lives directly below Elisa and right above a movie theater somewhere in Baltimore. Summoned from the depths of an underwater apartment filled with floating furniture, his voiceover delivers the prologue, paraphrasing, “We are about to witness a tale of love, loss and redemption about an isolated princess without a voice and a monster determined to end it all.”

At first glance, Elisa appears to be trapped in a life of isolation, her world centered on hard-boiled eggs, masturbation and drudgery, her only friends the aforementioned out-of-work advertising illustrator, Giles – was he fired because he too was The Other, a not-so-repressed gay man? – and her co-worker and protector Zelda (Octavia Spencer as the Rock of Gibaltar), whom she also sees everyday at the government lab where they work mopping floors, cleaning toilets and sharing gossip.

Then one fine day a secret, classified experiment in the form of a strange and wonderful creature from the Amazon (natch) is rolled into the lab.

Instead of being frightened by “the asset,” the intuitive Elisa is intrigued; then empathetic; finally head over wet feet for the brilliantly designed and prostheticized Doug Jones. The roller-coaster ride that ensues is at once wild, crazy and scary, careening seamlessly in the blink of an eye from one genre to another.

Del Toro’s sleight of hand is worthy of Houdini, but are we watching “Beauty and the Beast” with gills?

Yes and no.

At the sidewalk chat on the steps of the Galaxy following the screening, del Toro revealed that he finds “the tyranny of normalcy horrifying.” Why should his “beast” have to become human to be loved when he is beautiful – in fact, a god – already? (Besides – spoiler alert – Elisa is much more like her amphibious amour than initially meets the eye.)

Del Toro who is in love with love clearly believes it is a many splendored – but very spiritual – thing. Elisa/Hawkins is mute because true love renders us speechless. Besides, when it is the real deal, the quicksilver emotion is better expressed through song rather than mere words, hence Alexandre Desplat’s abundant, ravishing score. Also, everything is in the gaze.

Why the title, “The Shape of Water”? “Because, as we said, this is a film about love and like water, when love hits, “it takes the shape of the vessel it occupies,” del Toro explained. And water – like love – can be hard enough to cut through diamond, but also soft and caressing.

Del Toro pays off his conceit in many in-your-face ways. His fantasy is literally all wet; the element, everywhere: in the constant rainfall, bathtubs and overflowing sinks, in tanks, on window panes and cobblestoned streets – and in the drops of moisture on the faces and bodies of our post-coital heroine and hero.

The movie is also a rhapsody in blues – greens and teal. The only red in the film signifies either blood or love.

And the only monsters in the story are the men in suits.

Or elsewhere, in uniforms.

“The Darkest Hour”:

Witness “The Darkest House,” directed by Joe Wright, another of the Big Movies of the Big Weekend, also about The Other, but in this rare case, the “Other” is truly evil, not just perceived as evil. He is a man (rather a true beast) named Adolph Hitler. His opposite, the protagonist of the film is bipolar and a drunk, an emotional wreck of a man who was also one of the most courageous visionary leaders the world has ever seen, a bulldog named Winston Churchill. The man’s eloquence, his gift for mobilizing the English language into a weapon of war and civic unity arguably saved the Western world.

Gary Oldman sat for five hours every day in a chair to become “Winnie.”

The screenplay by Anthony McCarten (“The Theory of Everything”) follows the first days of Churchill’s term as prime minister, just as Hitler’s grip on Europe is tightening and the Brits are considering appeasement. It covers a period of about a month between controversial Churchill’s highly controversial ascension to leadership in the wake of an appeasement policy of Hitler by the previous and now very ill PM, Neville Chamberlain. The interlude covers Churchill’s celebrated “Blood, toil, tears and sweat” speech (May 13, 1940) and his “We shall fight!” speech (June 18, 1940), both delivered to the House of Commons in Parliament, rousing the public to the imperatives of national defense against fascism.

Churchill – or rather his surrogates – is no stranger to the silver screen. The illustrious roll call of “WInnies” includes Albert Finney, Brendan Gleeson, Timothy Spall, Robert Hardy, Brian Cox and John Lithgow, who played the elder statesman in “The Crown,” the 2016 Netflix series about Queen Elisabeth II. But the buck stops here: if there is justice in the world, Gary Oldman’s superb, warts-and-all, full-bodied portrayal should make him a frontrunner for next year’s Best Actor.

The supporting cast is equally gifted: Ben Mendelsohn is the stuttering King George VI (of “The King’s Speech” fame); Kristin Scott Thomas, the unflappable though long-suffering Clemmie Churchill; Lily James (Queen Elisabeth II in “The Crown”), the prime minister’s ingenue secretary and cheerleader; Stephen Dilane as Churchill’s wily opponent Lord Halifax; and Ronald Pickup as the physically and politically ruined Chamberlain, a rat and a wolf in Saville Row clothing.

“I don’t believe in character,” Wright explained to the crowd at Film Fest’s closing picnic. “Character is a condition of circumstances. We create our being through the choices we make.”

Tipping his hat to both the director and star, two characters indeed, The Atlantic’s David Thompson had this to say: “We have the real man at last, and if the myth has been exploded we have the truth that is more enthralling than all the legends.”

And while we are on the subject of legends…

“Hostiles”:

Christian Bale in “Hostiles.”

We did not expect to see Joseph Campbell smiling down on us in a darkened theater over Labor Day weekend, but there he was in the person of 2017 Festival tributee Christian Bale, on a classic Hero’s Journey in director Scott Cooper’s “Hostiles. From the ordinary world where he receives a call, he sets out to meet his enemies and allies, he faces terrible dangers and conflicts, but after a roughly 1,500-mile journey (in this case), he is ultimately is redeemed and returns “home” a changed man.

The central idea of “Hostiles” is summed up in a quote by D.H. Lawrence: “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.”

And yes, “Hostiles” illustrates man’s inhumanity to man in all the breathtaking colors of the American West, captured without breathy hyperbole by cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagii and underlined by Max Richter’s elegiac score, which adds to the emotional heft of this great picture.

Cooper’s story, set in the untamed West of 1892, begins with rampaging Comanches raiding the isolated cabin of a white settler family and butchering all the inhabitants except for the mother, a luminous, pitch-perfect Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike). She manages to hide.

A few clicks away at a nearby fort in the Arizona Territory, the Indian Wars are dying down and the commanding officer is told to have an ailing, longtime prisoner, Chief Yellow Hawk (the iconic Wes Studi) escorted from Arizona back to Montana, his homeland, to die.

It’s an assignment the badass veteran Captain Joseph J. Blocker (Christian Bale), at first refuses.

Bale’s Blocker is a complex character who studies the life and times of Julius Cesar for fun and Bale himself is a complex, physical actor who inhabits each and every strange, sometimes loathsome character he has played over the years, including a sociopathic killer in “American Psycho.”

Bale and Studi facing off.

As with Elisa in “The Shape of Water,” it’s all in the gaze: witnessing Bale’s physical and psychological transformation close up, his Hero’s Journey, is a thing of beauty. Like Brando, he can say it all in close-up without saying a word. Learning about his opponent Bale/Blocker learns about himself and in so doing, he buries his devils.

The muscular, no-frills performance has to be one of Bale’s greatest ever. It certainly makes him an instant Oscar contender.

And by leveraging Western tropes, turning them into universal truths, Cooper succeeds like never before in telling a uniquely American story that resonates today in a world of racial and cultural divisions. The real violence in this, yes, very violent film is the violence done to the human soul out of ignorance.

In the end, “Hostiles,” on the top of everyone’s list of weekend favorites, is a meditation on empathy.

“A Man of Integrity”:

Director Mohammed Rasoulof, “Man of Intergrity.”

In America, ignorance about Iran as The Other reduces the culture to a pack of crazed terrorists. The truth, obviously way more complex, though no less terrifying, is beautifully, revealed in director Mohammad Rasoulof’s (ironically titled?) “A Man of Integrity,” clandestinely shot in the north of his country, where he is banned from making movies.

In an interview with Mark Danner, a writer on foreign affairs for The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books, Rasoulof explained that his title in Farsi is “Lerd.” Lerd is what falls to the bottom when you make wine. It is the sediment or the dregs. The director believes that society’s problems come from the top down, from those in power. Eventually sediment floats to bottom and infects the general population.

The metaphor is all too clear: Iran is country in which the director says “you’re either the oppressed or the oppressor.” But this scathing critique of Iranian society resonates all too loudly here at home.

Are we in immediate danger of losing our moral center too?

As Danner explained in his intro to the film: “Even if you are not a political man, politics will find you.”

“A Man of Integrity” is a powerful film quietly, eloquently told by a courageous truth-teller and his two leading actors.

At the screening we attended, Rasoulef explained: “I can’t say ‘enjoy’ my film, but I hope you find your time well spent.”

We did.

“Battle of the Sexes”:

For years, even after women got the right to vote in 1919, we have been considered. mostly by the Ruling Class, WASP males, as The Other.

Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs, 1973.

Just ask the legendary tennis star Billie Jean King, an Other twice over, a gay woman – and a special guest at Film Fest, here with the film that provides insight into her legend.

In a perversion of the leitmotif, when The Other is the professional misogynist and tennis phenom Bobby Riggs, (Steve Carrell in an almost all too believable portrayal), you laugh out loud.

Emma Stone and Steve Carrell as King and Riggs. The resemblance is uncanny.

Billie Jean is Emma Stone – just ask Billie Jean who lavished praise on the actor for her body-snatching performance – and as Billie Jean, she returns with the wind under her sails to the Oscar arena, where last year the actress won for her work in “La La Land,” also launched at Telluride Film Fest.

The very personal sports drama, directed by “Little Miss Sunshine” duo Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, in which the tennis icon fights (and continues to fight ) for gender equality and wins, was universally praised on lines around town and online.

Stone and Carrell both aced this one.

As did Annette Bening in “Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool,” a warm and tender love story directed with respect and restraint by Paul McGuigan. The movie is about an improbable December-May romance between an aging, but still beautiful Oscar-winning actress, who becomes deathly ill and a struggling young actor, (a callow but convincing Jamie Bell), her lover in better days. It helps to know “Film Stars” is also a true story, so Bening is no Mrs. Robinson: the book is based on a memoir by Peter Turner, who announced the film and loved who he loved.

Bening and Bell, in love and so what?

Once again, del Toro proves himself right: love has little to do with surface and everything to do with finding a soulmate – and chemistry, which is ineffable.

Fact is Bening has received four nominations across two decades for Best Actress. Could five be the charm?

“The Rider”:

When Werner Herzog introduced “The Rider,” his enthusiasm was unapologetically over the top: “It’s better than anything I’ve ever seen.” Which strangely echoes a review of another film that premiered in Telluride, “Moonlight,” described by Matt Jacobs of the Huff Post as “…most important thing to appear on the big screen this year.”

Brady Jandreau is The Rider.

“The Rider” is this year’s “Moonlight,” an idiosyncratic, wholly undecorated portrait of a slice of Americana that might otherwise fly below the radar – or in the case of “The Rider,” be lost to the flyover that is all too often the Midwest. (Think the Steinberg cartoon.)

“Moonlight” focused on the drug- and crime-riddled black neighborhoods of South Miami, close to where director Barry Jenkins and Tarell Alvin McCraney grew up.

“The Rider” focuses on cowboy life on what was once the frontier and today is the quiet, desolate backwater that is the badlands around Pine Ridge, South Dakota. In a voice redolent of the voices of Cormac McCarthy, Jim Harrison, Larry McMurty, Annie Proulx and Lydia Peele – read spare and unsentimental – director Chloé Zhao tells a tale of cowboys, bull and bronco riders, in a unique hybrid of feature and documentary.

The focus is on the Jandreau family, real people, not actors, particularly on Brady Jandreau, a bronco rider and horse trainer recovering from surgery following a head injury. Brady’s sister Lilly, who is autistic, is played by Lilly Jandreau. Brady’s real father Tim plays the dad. And the severely disabled Lane Scott, Brady’s fellow rider, his one-time mentor and closest friend, also bravely plays himself.

“Lane Scott is the heart of the heartland,” said Herzog.

Asked on a panel about whether or not she scripted “The Rider,” Zhao affirmed that she had written a 55-page skeletal script, but then the rest was improv.

“I knew the family for two years before Brady’s accident. They trusted me. My goal was to capture their emotional and visual truths. Capture how their life feels.”

Does Zhou succeed with her drama? For more, read Clint Viebrock’s review here of “The Rider” and “Lean On Pete,”

“The Cotton Club Encore”:

It was exactly as Huntsinger and Luddy promised, just as magical: “The Cotton Club Encore” – according to Luddy, the 1984 Oscar-winning film Francis Ford Coppola wanted to release, but was overruled – tap-danced its way into our hearts.

The film is set in 1920s/1930s New York, when gangsters and guns could buy guys and dolls and black lives did not matter – except to entertain rich whites who filled the clubs where they starred, but could not enter through the front door.

“Encore” includes moments like “Stormy Weather,” sung by the stunning Lonette McKee as Lila, also 20 minutes of footage featuring Richard Gere – what chops – Diane Lane, Gregory and Maurice Hines, that originally wound up on the cutting room floor.

Coppola, Maurice and Zachary Hines were on hand at the screening to tell tales and bask in the loud applause. Made for a uniquely Telluride moment.

Buzz Feed/Grab Bag:

Greta Gerwig’s semi-autobiographical “Lady Bird” is a charming, witty, insightly directorial debut. A beloved indie release based in Sacramento, where the writer-director was raised. Great performances by Laura Metcalf as the Lady Bird’s mom; Saoirse Ronan as Gerwig/Lady Bird; and Tracy Letts as her dad.

Greta Gerwig and Saoirse Ronan.

In Randy Newman’s controversial “Short People,” the verses are lyrically constructed as a prejudiced attack, but the bridge states that “short people are just the same as you and I.”

Alexander Payne’s ‘Downsizing” lends heft to that idea. And yes, the film is about The Other – “normal”-sized peeps v. Lilliputians – but its primary focus is climate change and how going small or downsizing can make a big difference.

Kristen Wiig and Matt Damon star in “Downsizing.”

“Downsizing” is smart, funny and very quirky. Hong Chau’s performance is intimate, funny, smart – and a bit stereotypical.

We had fun; others not so much. But let us ask you the question sticking in our noggin: Would you exchange 99.9636 percent of your body mass and volume for a 9,900 percent increase in the value of your assets if it also meant saving the planet?

“The Insult,” the latest release from Lebanese director Ziad Doueiri, is a courtroom thriller that examines the question of guilt, justice and honor in the Mideast. Friends told us it was hands-down the best of the fest.

Scene form “The Insult.”

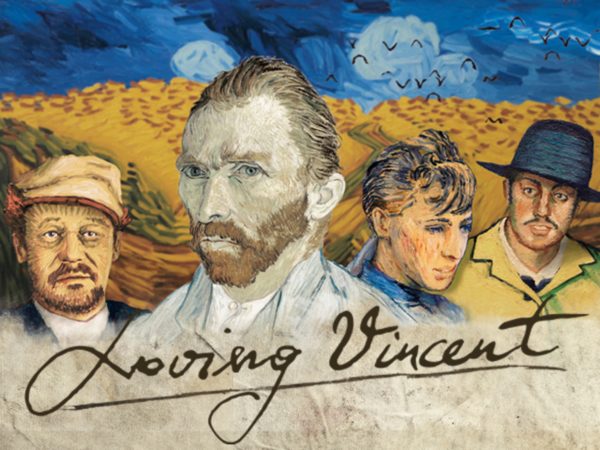

“Loving Vincent,” a unique biopic – it appropriated the artist’s impasto style using 65,000 frames of hand-painted, animated oil paintings created by 100 artists – was highly recommended as an impressionistic expression of creativity in action. The film also examines the mystery of the artist’s last days.

At the screening of “The Shape of Water,” I was encouraged to see “Wonderstruck,” a tale of two lost and impaired children finding each other across time.

“Haynes has always been a ravishing visual storyteller, and his seventh feature is as seductively crafted as anything he’s made, with exquisite contributions from invaluable frequent collaborators including cinematographer Ed Lachman, production designer Mark Friedberg and costumer Sandy Powell. Perhaps even more notable here is the work of composer Carter Burwell, who has created distinct musical moods for the narrative’s parallel threads, following the adventures of two runaway deaf kids 50 years apart, with the sounds subtly folded together as their stories intersect,” wrote The Hollywood Reporter.

Two press pals mentioned that “First Reformed” was at the top of their picks, though several folks on the street, said quite the opposite, describing the film as weird, slow and pretentious.

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Maria Laura Antonelli/REX/Shutterstock: Paul Schrader, Ethan Hawke, Amanda Seyfried

‘First Reformed’ photocall, 74th Venice International Film Festival, Italy, 31 Aug 2017

“Per the film’s official synopsis: “‘First Reformed’ is a film about spiritual life starring Ethan Hawke as the minister of a small, historical and empty church. An ex-military chaplain, Toller (Hawke) is tortured by the loss of a son he encouraged to enlist in the armed forces. As Toller struggles with his faith, he is further challenged after a young couple, Mary (Amanda Seyfried) and her radical environmentalist husband Michael, come to him for counseling. Consumed by thoughts that the world is in peril and motivated by the church’s lack of action, Toller embarks on a perilous self-assigned undertaking with the hope that he may finally restore the faith and purpose he’s been longing for in his mission to right the wrongs done to so many. Our exclusive new look at the film indicates, at the very least, an uncomfortable closeness between Hawke and Seyfried’s character that should push the film into some intriguing new spaces,” wrote Indiewire.

Produced and narrated by Natalie Portman and directed by Christopher Dillon Quinn, “Eating Animals” is not preachy or polemical, not militant vegan in any way, but it does force us to confront where our food comes from. And it is mostly not pretty.

Natalie Portman, holding up the book by Jonathan Safran Foer upon which her movie is based.

Highly recommended for meat eaters. Or for anyone with an interest in saving the planet from global warming and pollution. According to online sources, the global livestock industry produces more greenhouse gas emission than all cars, planes, trains and ships combined.

“‘Eating Animals’ may be the most important documentary that screened this year at the Telluride Film Festival, though it could be hard to get audiences across America to watch it,” wrote the wrap.com.

Chew on that.

Paul Lehman

Posted at 12:38h, 06 SeptemberExcellent reviews Susan of some great movies. Thanks for the insights,

Pingback:Fall Films Not to Miss | Telluride Inside... and Out

Posted at 13:39h, 16 September[…] Telluride Film Fest 2017: Another Monster Weekend – September 5, 2017 […]