01 Jul Telluride Gallery: James Hayward, In the Thick Of It All, Opening at Art Walk, 7/6

Telluride Arts promotes a culture of the arts within the Telluride Arts District, which contains a remarkable concentration of activities that engage artists from around the region and across the globe. Telluride Arts’ First Thursday Art Walk is a festive celebration of the art scene in downtown Telluride for art lovers, community, and friends. Participating venues host receptions from 5 –8 p.m. to introduce new exhibits.

A free gallery guide offers a self-guided tour that can be used any time to find galleries open most days. Guides are available at participating spaces and at the Telluride Arts offices at 135 West Pacific, across the street from the Telluride Library. For further information, you can call 970-728-3930.

For other July Art Walk shows, go here.

The big show opening with this month’s Art Walk, Thursday, July 6, is James Hayward at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art, (July 4 – August 8).

“In perception we do not think the object and we do not think ourselves thinking it, we are given over to the object and we merge into this body which is better informed than we are about the world,” philosopher Merleau-Ponty, quoted in a book about James Hayward’s work.

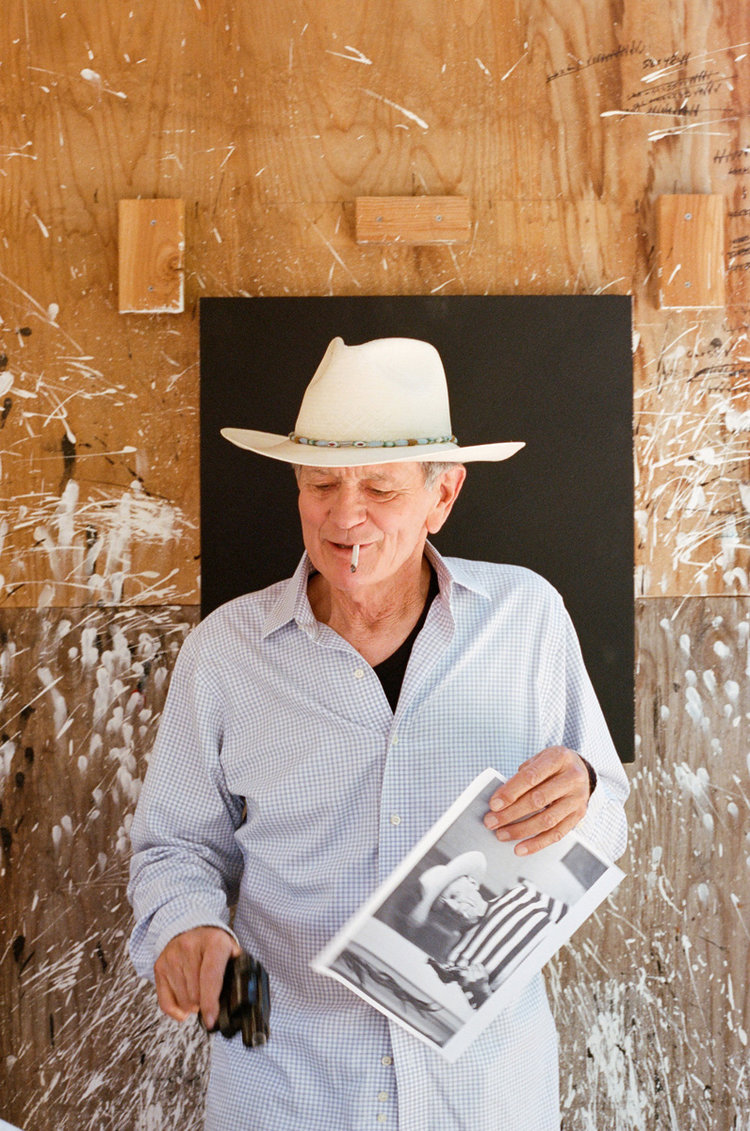

James Hayward, courtesy Flaunt magazine.

Artists, like cowboys, live an edge life somewhere between hard, isolated, isolating work, and the mythology that surrounds that whole daggum picture.

James Hayward is the real McCoy, a cowboy generally tricked out in full regalia – hat, boots, tired jeans, a burning joint hanging from his lips. His family has been breeding Arabian horses since the early 1970s, first in Bellevue,Wshington, than on a big spread in Moorpark, just north of the City of Angels. Hayward’s home for years on that property is modest to say the least: an aluminum trailer, plus a studio and office/storage space for work.

James Hayward is also a celebrated artist, art historian, and teacher – and father of Ashley, new co-owner (with husband Michael Goldberg) of the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art. His upcoming show at the gallery officially opens with Telluride Arts’ Art Walk. That celebration of the local art scene takes place Thursday, July 6, and runs through August 8.

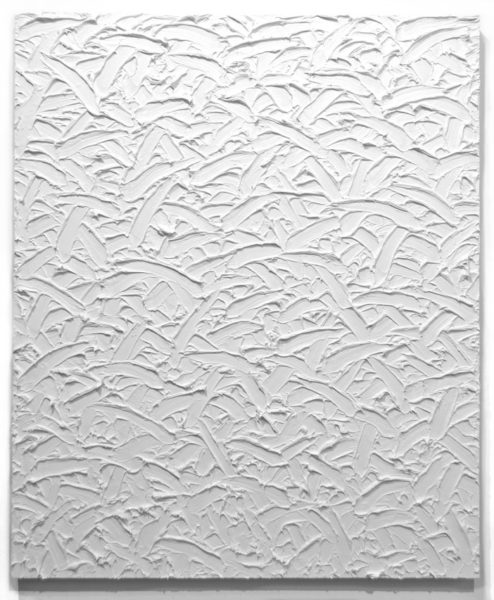

Asymmetrical Chromachord #22

“What I enjoy while viewing Hayward’s paintings is the rhythmic presentation of his highly saturated, intense color studies. The paintings begin to vibrate through the mark-making; the energy that Hayward interjects into the brushwork is palpable. The blended multicolor works are equally intriguing because the viewer witnesses his color mixing directly on the surface,” wrote Malarie Reising Clark of the Telluride Gallery. “And when it comes to color, Hayward is an equal opportunity painter. The intense primary colored triptych does not outshine the grey and white diptych, both are saturated, bold, and packed with layers; both mesmerize the viewer through the in-your-face brushwork. The Telluride Gallery of Fine Art is overjoyed and honored to exhibit artwork of this caliber and to have an artist like James Hayward present at Art Walk. What a treat for us and for our patrons.”

Triptych #5

On display are 21 paintings, including diptychs and triptychs.

“Regarding the colored diptych process, the left and right side panels began with the same four colors selected for the painting. My father then made a deliberate decision to leave the canvas on the left barely blended and the one on the right further worked, thus creating a sumptuous and unique fifth color,” explained Ashley Hayward, who continues:

“I would describe my dad’s paintings as visual meditations. The mind gets lost, while the eye dances across the surface. It’s amazing to me how his works continue to reveal themselves to the viewer the longer he stays in place and observes. I have literally seen people transformed in amazement in front of Jimmy’s paintings. I understand that reaction. First you are struck by the beautiful, bold, heavy impasto brushstrokes, then the subtleties of the colors consume you. Finally you get lost in the rhythm of the marks, then more color variations and the play of light and shadow take hold. Truly a symphony for the eye and a delight to experience.”

Diptych #7

It all began for the nonrepresentational painter when, at age seven, he won a Smokey the Bear drawing contest – but soon discovered he was not so good at drawing people. Since then, Hayward has won countless laurels for his hard-edged monochromes abstractions. He has had shows at major museums including the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Gallery shows have included Roberts & Tilton in L.A.; Peter Blake in Laguna; and Modernism in San Francisco. In 1984, James Hayward also won a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship to work in Japan, a trip that triggered the artist’s move from flat blocks of color to thickly painted (mostly) monochromes.

In fact, Hayward’s work divides between those two themes and periods: flat, early (1975-1984) and thick, later (1984-present).

The focus of his Telluride show is thick.

Diptych #42

So thick in fact, the sheer weight of the sensuous, expressive abstractions on display appear to defy gravity. Why don’t those roiling impasto crests collectively ooze right off the vertical picture plane like an erupting volcano? How is it those rambunctious monochromes, highly saturated wild waves of luxuriant color, don’t spill right off the canvas onto the gallery floor like an angry ocean flaunting its power?

Magic, right? Yes, of sorts. The explanation lies in dizzying sleight of hand that can only happen when the eye stops legislating and censoring and willingly yields to the hand with a brush. The hand then takes off in a fury that results in a vibrating, eye-dazzling, meditative whole, creating a muscular mandala.

Abstract #238

And where is the artist in all this?

Lost in an improvisation: in that frenzied process of marking, the painting is painting the artist.

Trying to contain the resulting all-over image is like trying to hold onto an extended jazz riff: quicksilver morphs as soon as you attempt to contain it.

Once hypnotized himself, the artist now hypnotizes his captive audience.

In full disclosure, what’s hard to catch is all the more seductive.

Don’t scan for information on the surface. It’s all in the surfaces. Surf the surfaces. You should then find it easy to loose yourself in the swirls and twirls that shape the reflected light.

“…the heart and soul of it is the marking. In my monochromes I try to avoid there ever being a special place. There’s no chosen place. It’s totally proletariat, the marking. I want the corners to be as important as the center and I want every mark to be equal in terms of importance. Ideally, the last marks just kind of blend into the earlier marks and disappear,” Hayward told a former student in an interview in Artillary magazine.

Hayward’s magic trick, however, is nothing new. It dates back to the Renaissance, gets passed on through to 19th-century masters like Cezanne and Van Gogh, then heads across the pond and up the road apiece to the New York and the Abstract Expressionists of the 1940s and 50s.

Abstract Diptych #41

When did modern art begin? Are its roots tangled, as many historians believe, in the subsoil of the 19th century, in the work of Cezanne and the thick, slashing, maniacal brushstrokes of Van Gogh? (Squint at a Van Gogh, loose the representation, and you will spot a Hayward, promise.)

Arguable yes, though not for Hayward. He traces the roots of his creative voodoo to Titian as a quavering old man and the artist’s late period from 1548 to his death at age 80 in 1576, and particularly to his painting of “Venus Blindfolding Cupid,” 1565.

Titian’s “Venus Blindfolding Cupid.”

The story goes that after his return to California from Japan, in 1999, Hayward was invited to show in Milan. He made three working trips to Italy between 1999 – 2001, staying at the American Academy in Rome, where his intense admiration for Titian’s late paintings emerged.

At the Galleria Borghese. Hayward discovered “the deceit of control and the true beauty of paint unleashed.”

“…Yet in his own age, it was said that the Venetian artist was forced to use his fingers to blend colour on the canvas because he could no longer hold a brush. He was mocked as an old man who made ‘patchy pictures’—pittura a macchia.

“But is it possible that Titian painted like this on purpose, using his failing eyesight and trembling hands as a cover to experiment with layered colour and a more open and fluid brushwork that lent greater movement, emotional depth and animation to his figures?,” wrote an insightful critic in The Economist.

“Not satisfied to wait for permission that comes with old age, Hayward has explored the opposing tendencies of painterliness and the controlled surface from the outset,” wrote Frances Colpitt in a book about the artist.

GAWA4, 1990

If it walks like a duck…?

Could James Hayward be an Abstract Expressionist? His work does appear to evolve from that testosterone-infused lineage.

But here’s the truth: Willhem de Kooning was once quoted as saying it was “disastrous” to saddle his loose confederacy of painters with that clumsy handle. Few of that group actually made abstractions anyway. It is impossible to look at the work of Mark Rothko or Clyfford Still without thinking of a landscape, spiritual or otherwise. And there was no coherent style that bound the kinetic skeins of Jackson Pollack with Rothko’s luminous soulscapes. There was no core manifesto either. What’s more, other than de Kooning, all of them – including Pollack, Robert Motherwell, Adolf Gottlieb William Baziotes, Barnett Newman, etc. – adhered to the primordial and primitive and bowed to the influence of Surrealism, which stressed the power of the unconscious.

Abstract #236

“Far from being nonreferential artists, the Abstract Expressionists were obsessed with the search for subject matter, the more exalted, the better,” said art historian Robert Hughes.

Which is not Hayward.

“I ask him why his paintings aren’t referred to as AbEx? ‘Because the marks have no meaning. Each mark is (pause) they’re pretty much all the same. In a way it’s more like music than Abstract Expressionism. It’s like free-form jazz or something. It’s just marks piled up and piled up,” explained the artist in Artillary.

“Through chromatic density, shaped by the humanity of each restless mark, Hayward’s paintings open onto a world of oneness and wonder,” wrote Colpitt.

And wonder, nothing more, nothing less, is the point of Hayward’s prodigious efforts.

If there is a point beyond the paintings themselves …

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.