18 May EARTH MATTERS: WHEN BUSINESS & GOVERNMENT MIX

Corporations and government do mix. But the result can be a toxic concoction. Quite literally, especially when transactions involve agricultural and food policy.

Corporations and government do mix. But the result can be a toxic concoction. Quite literally, especially when transactions involve agricultural and food policy.

While corporations do bring important information to the table and have a definite role to play in the regulatory process, when corporate representatives become regulators themselves, the line between what is best for the citizens and what is best for the bottom line can become very fuzzy. Unfortunately, far too often, there is a “revolving door” between regulators and industry representatives that allows people to go back and forth from one institution to the other. Indeed, opensecrets.org has several webpages dedicated to tracking individuals through the revolving door. (See http://www.opensecrets.org/revolving/top.php?display=I)

The concern here is one of “regulatory capture,” where regulators end up serving industry instead of the public. Former industry representatives can certainly make good regulators because they have an intimate understanding of the regulated industry, the issues involved, the regulations themselves, and industry business practices. But they can also bring with them a mindset carried over from their time as corporate representatives, favoring industry profits over citizen health, safety, and welfare. As for movement in the other direction, there is very little good to be said about it. Generally, corporations pay former regulators for their knowledge of how to navigate the regulatory process most efficiently and, even more, for their agency contacts.

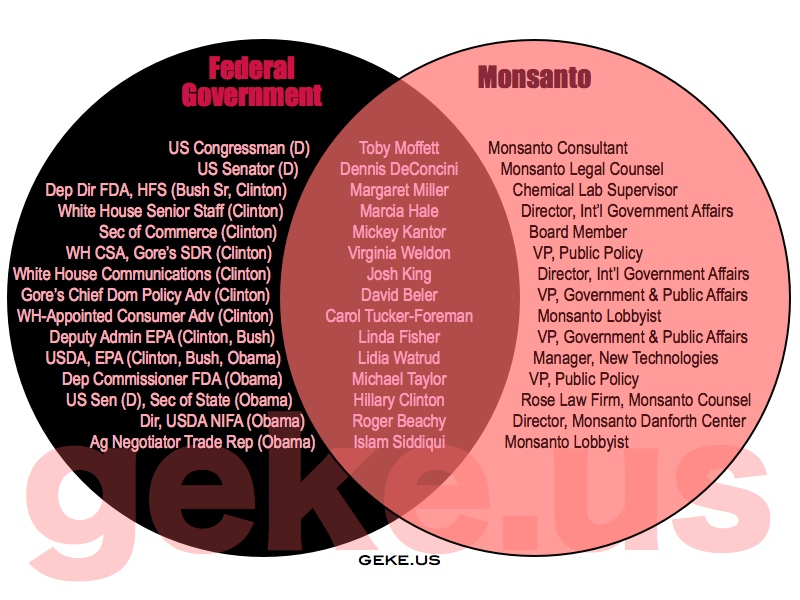

Concerns about the role of industry lobbyists led the Obama administration to create a policy to try to prevent the most egregious instances, announcing in 2009 that registered lobbyists should not be appointed to agency advisory boards and commissions. Nonetheless, that has not kept the revolving door from turning, as is evident from the figure depicting US government-Monsanto links.

The problem is exacerbated by growing corporate consolidation. Recent news that Monsanto bought out Beelogics, the leading company conducting research into Colony Collapse Disorder – for more on CCD, see my earlier story about neonicotinoids – set off alarm bells among beekeepers, farmers, and activists who fear that if Monsanto controls the research, they also control the storyline.

The trend is not limited to Monsanto. Over the last two decades, the movement has been towards increasing consolidation in the life science industry. For example, ten main companies control over 80 percent of pesticide market, with the “Big Six” – Syngenta, Bayer, Monsanto, BASF, Dow, and Dupont – controlling 68 percent. (See http://www.panna.org/issues/pesticides-profit/chemical-cartel).

With this kind of power consolidation, industries can exercise enormous control over all aspects of the regulatory, marketing, research, and sales process. It is also more likely that the kind of experts regulatory agencies often hope to place in key positions will have connections to the main industry actors. In addition, when only a few corporations wield extraordinary market influence, supporting businesses and related organizations are increasingly tied to them as well. This is where things get really interesting.

A Harvard Business School study by Shon Hiatt (an assistant professor who grew up on an Idaho dairy farm) looked beyond the more obvious issues of revolving doors and regulatory capture per se to examine exactly how corporations sway the actions of federal agencies and elected officials. Hiatt posits that it is not direct influence so much as the search for legitimacy that drives federal agency decision making. That is, federal agencies want their decisions to be validated and justified by third-party groups. Hiatt claims, as an example, that the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) in regulating genetically modified organisms (GMOs) looks for “consequential legitimacy” – is the process seen as effective? – and “procedural legitimacy” – does it follow the rules?

(See a more complete account, along with a link to the full working paper, at http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/6959.html)

How can this create problems? Well, the third party groups the USDA looks at in regulating GMOs include two main sectors: first, farmers’ associations, like soybean or corn growers, and second, other regulators, in this case mainly the U.S. Food and Drug Association. Farmers’ associations, while not directly controlled by the life science corporations, are heavily influenced by them, especially for major crops that are most likely to use GMOs such as soybeans, corn, cotton, and rapeseed. It is difficult for most farmers to avoid working with big corporations, and farmers’ associations can even have industry representatives as members.

This influence is not minor. With support from these third-party groups, the USDA is much more likely to approve products: 84% more with farmers’ groups’ support, 157% more with FDA support. Also, according to the Harvard Business School article, “In addition to increasing the likelihood of approval,” says Hiatt, “third-party endorsements shorten the approval period. With farmers’ approval, agricultural companies shaved about 162 days off the average approval time; with FDA consultation, they cut it down by about 257 days. That can translate to big bucks for companies.”

So a mix of regulatory capture, a revolving door between industry and the agencies that regulate it, industry consolidation and control, and agencies’ looking for love in all the wrong places can and very often does lead to bad regulatory and legislative decisions when it comes to human and environmental health.

What steps can we take to change this situation?

In the food and agriculture arena, our consumption habits can make a difference: we can buy organic, buy local, and/or buy directly from farmers. We can take action to ask our elected officials to prevent regulatory capture; for example, asking President Obama to drop Michael Taylor, a former Monsanto lawyer, as food safety “czar.” (See http://www.organicconsumers.org/articles/article_25275.cfm for a call to action by Organic Consumers Organization).

Helping agencies become more self-aware is also important. Finally, we can support the efforts of organizations like the Center for Responsive Politics which work on improving governance, and PANNA, OCA, and other organizations that work on improving agricultural practices and policies. There are hundreds of great organizations working on these issues locally, nationally, and globally, so I’m listing these particular NGOs just as examples, not as exclusive ideals.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.